The Simon Community was a small and impeccably stubborn charity which refused to accept any government funds or government rules; it had no paid staff and was simply a collection of street homeless people and volunteers trying to live together communally.

This was the era of the cardboard city, with large numbers of long-term rough sleepers clustered together in Central London. Many of them were Irish or Scottish, nearly all were men, and many of them had been sleeping rough for 20 or 30 years.

Crude spirits were still a problem, meths and surgical spirits, with the appalling consequences that they have on people’s health. But in the years that I spent living there, I saw the world of homelessness changing before my eyes.

As the old guard were dying out, we began to encounter more and more young homeless people living on the street. The Thatcher government had introduced swingeing cuts to benefits entitlements for those under 25, and those without family support – and especially those who had been brought up in care – were being left destitute.

It made me keenly aware that, while each person’s personal journey into homelessness was unique to them, the pattern of who was most at risk of falling by the wayside could be determined by the stroke of a pen in Whitehall.

I left after three years, with nothing to my name but a tent, a girlfriend, and an ancient Triumph Bonneville motorbike, and set out to tour Britain. We ended up on the Isle of Jura in the Inner Hebrides, a place that I fell in love with, perhaps in part due to the sheer contrast with the crowded, busy life I had been leading.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

I then set out around the world, hitch-hiking and picking up casual work when I could, and stayed away for years.

When I finally returned in 1988, I found myself with no job, no money, and no home. With no other option facing me, I opened a squat in North London. I had thought it would be a temporary respite, but in the event, it would remain open for nearly two years. It was a huge place with around 15 bedrooms; perhaps ironically, it had formerly been a children’s home which had shut down due to government cuts.

It turned out that the world of homelessness had changed once again during the years I was away. It was now a much more multicultural affair, and the squat filled with people from all over the world; people with nowhere else to go. At first it was fine, but as is so often the case with large squats, in the end it all went to pot. You cannot exclude anyone when everybody has as much, or as little, right to be there as anybody else.

We came to the attention of the local drug dealers and shoplifters, and they forced their way in mobhanded. The place turned to chaos, with a constant threat of violence in the air.

Without resorting to spoilers, there was finally an incident that took place which forced me to question who I had become, and I realised I needed to take drastic action.

I got up one morning and set out hitch-hiking, and carried on until I once again reached the Isle of Jura that I had fallen in love with all those years before, and walked the entire coastline of the island.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

And there, sleeping out on the uninhabited west coast of the island, I like to think that I found a way to come to terms with myself.

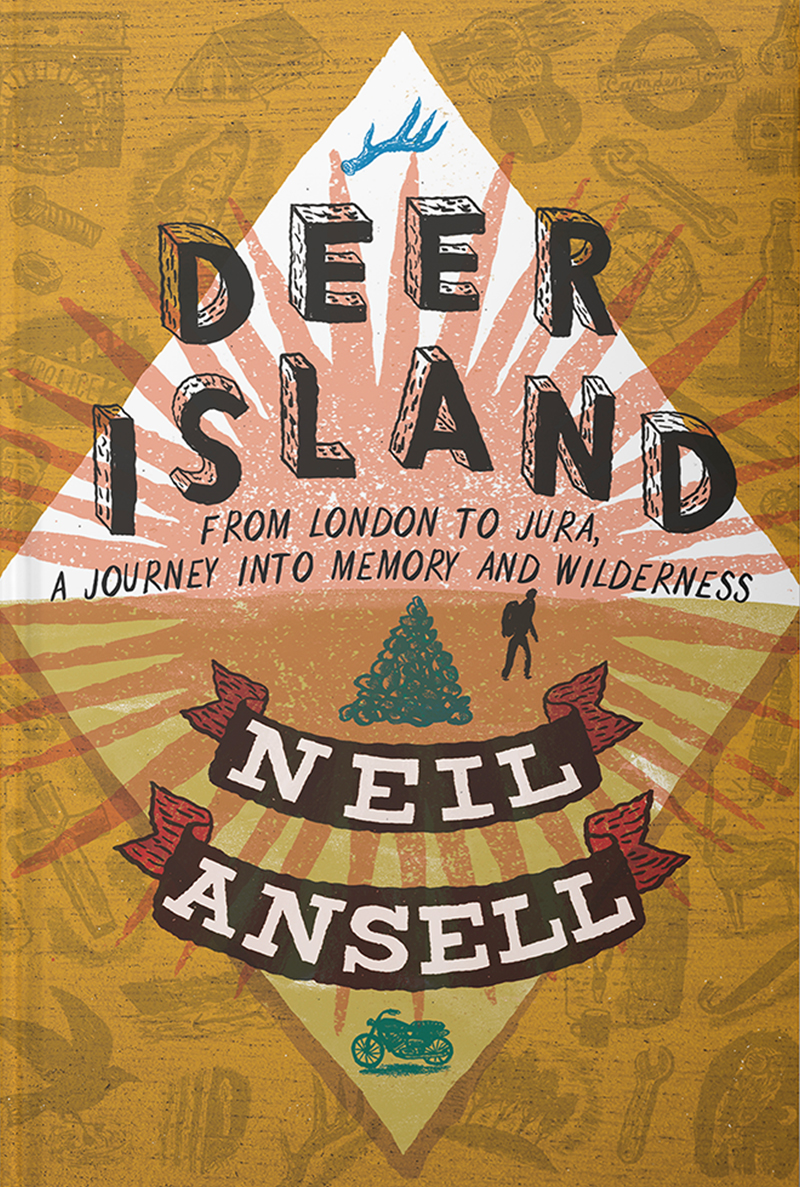

Deer Island by Neil Ansell is out now in paperback (Little Toller Books, £10). You can buy it from The Big Issue shop on Bookshop.org, which helps to support The Big Issue and independent bookshops.

This article is taken from The Big Issue magazine, which exists to give homeless, long-term unemployed and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. To support our work buy a copy!

If you cannot reach your local vendor, you can still click HERE to subscribe to The Big Issue or give a gift subscription. You can also purchase one-off issues from The Big Issue Shop or The Big Issue app, available now from the App Store or Google Play