We’ve all heard the line, variously attributed to Elvis Costello, Frank Zappa, Thelonious Monk and even Clara Schumann (though the last seems unlikely): “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.”

It’s a cliché. But while dancing about architecture would undoubtedly be tricky, you could try. Certainly, millions of words have been expended on attempting to explain and account for music, and the trouble starts with defining the term.

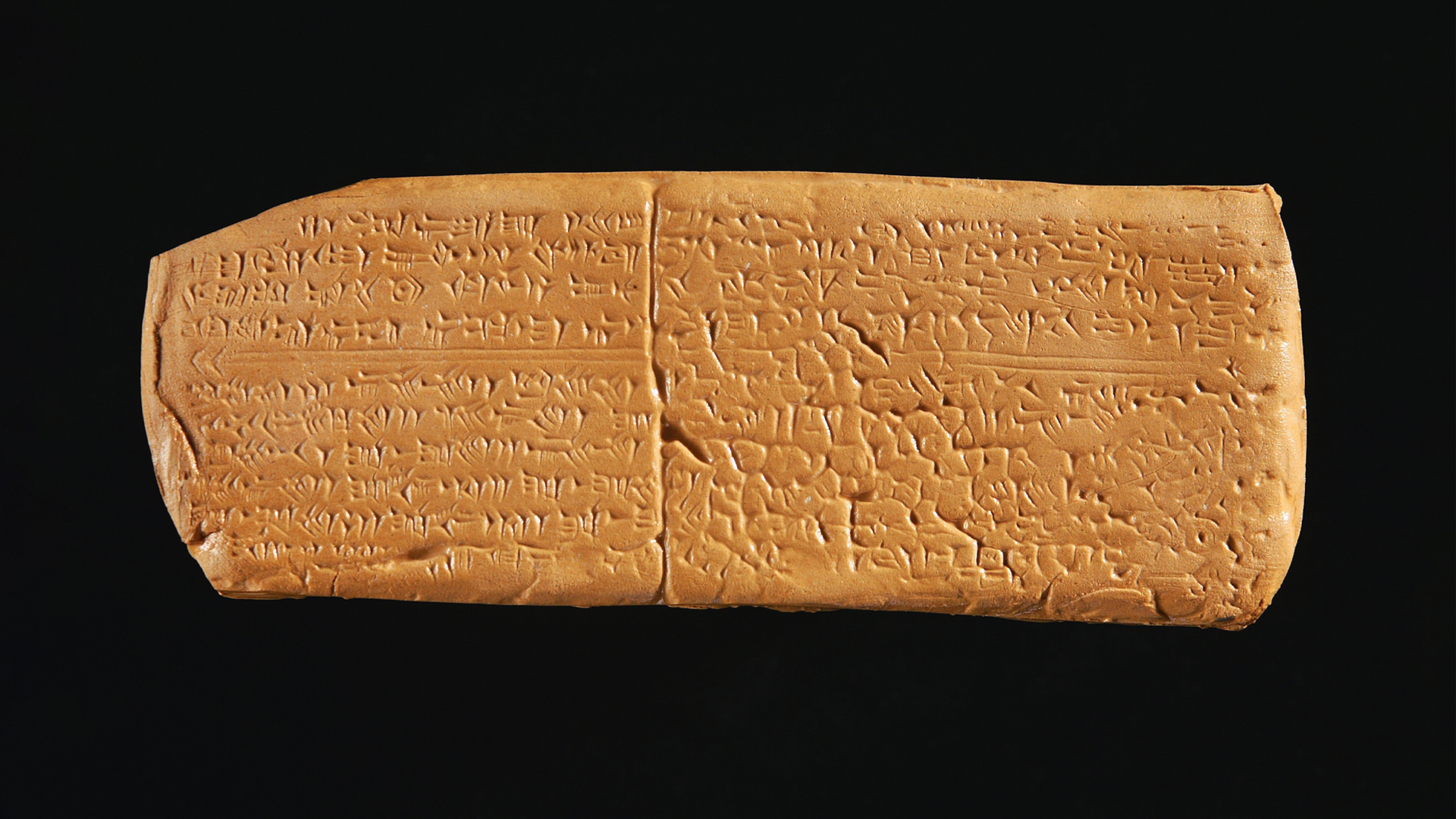

Most of the indigenous languages of Africa, though they have words for singing and storytelling, dancing and playing instruments, lack a word for music. Equally when human beings have made tuneful sounds to assist them in their work (field hollers, sea shanties), or to praise their gods or for any sort of ritual, they’ve probably not been thinking first of the nature or quality of their musical utterance. Many branches of the world’s religions, disapproving of what they consider to be music, find other words to describe the singing and chanting of scriptures and prayers.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

The American composer John Cage said music was “organised sound”, which is a nicely inclusive definition, leaving room for the organising to occur in the mind of the listener. But Cage’s definition misses music’s importance, and it’s that importance that gives it its place in our lives and in history. Music is so important and so ubiquitous, that we can easily get suckered into the belief that it’s an international language – another cliché. In fact, it is neither international nor a language. If it were genuinely international, we’d all understand all of it. But everyone’s heard music that means nothing to them. “That’s not music!”, we say.

As for being a language, if it were, you could convey specific information in it – you could write a shopping list or give someone directions – and you could translate it into another language. No one believes this is how music works.