AB: I believe that addiction is a perfect storm of genetic vulnerability and family modelling. Understanding the nexus between these two factors is a life’s work in recovery. For me, I can say that an early familiarity with alcohol in the domestic setting – alcohol at lunchtimes, any and every occasion celebrated or commiserated with a drink – led to an association between alcohol and the feeling of home. When we were writing the book, mum and I spoke a lot about the concept of home – both literal and metaphorical – and we arrived at the conclusion that for a long time, that was what alcohol felt like.

How did you find a way to help each other rather than exacerbate the issues you both faced?

AB: Helping each other in recovery involves a delicate dance of staying close to each other and the programme but also knowing when help from an AA sponsor or recovery fellow might be more appropriate, times when we might trigger each other unnecessarily.

JH: It wasn’t easy to start with, but we learned in AA that helping each other quite often meant talking to someone else first, as Arabella said. Addicts are notoriously un-boundaried because they’re always shifting the goalposts around to justify bad behaviour, a practice that often continues into sobriety. We had to learn new ways of doing things in order to help one another and it took time.

If you could go back in time, what would you do differently?

AB: I count myself extremely lucky to have got sober at the age of 26. I found recovery early and have lived 14 excellent years without a drink or a drug. You often hear people say in meetings that they wish they had found the programme earlier and I feel their pain acutely. I guess you always feel that you could help more people into recovery and I wish that my father had found healing in the last years of his life. Holding the sadness of not being able to help him and the possibilities of a sober life in both hands is a daily practice.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

JH: I would have gone to AA aged 25 (when I first rang them) and got sober, as my daughter did in her twenties. Waiting until you’re in your early fifties simply means so much more chaos and hurt, to yourself as well as everyone else. Don’t wait – just do it! If you’re an alcoholic, it’s never too soon to stop! You often hear young people saying that their youth stopped them but my experience is once you’ve become an alcoholic (or an addict of any kind), young or not, addiction withers everything it touches, whatever age you are.

Why is addiction among women not spoken about much in society?

JH: Women addicts very often have children. Sometimes they are, as I was, single parents. Owning up to addiction might mean social services get involved, with everything that means. A lot keep quiet and don’t seek help as a result. There’s also the fact that women are mothers and keepers of the hearth. The fact that a mother will push aside the body of her child to get a drink or a drug is simply unpalatable to many people. It doesn’t fit with society’s view of alcohol in particular as a happy, blessed place. We badly need to adjust our ideas of what addiction looks like in women and break that deadly code of silence.

AB: I believe the messy business of female addiction sits uncomfortably with how society wants to enshrine women: as mothers, grandmothers and carers. To open up a conversation about female addiction is to destabilise persistent myths that we, as a society, hold dear. You only have to look at depictions of “perfect” motherhood on Instagram to see how much we long to keep women in certain roles. I hope we can begin to break the code of silence among female addicts by challenging assumptions around what an ‘alcoholic’ looks like; she might look nothing like you expect.

Is it in the blood?

AB: Definitively answering this question would be very hard. Part of the impetus to write the book was to ask the question that remains taboo: did the darkness start with me? Inevitably, the answer is not straightforward and one of the challenges of the book was to take the reader on the journey of discovery with us, to show how we trod back through the past in search of clues.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

JH: It very often is. There’s a strong genetic component. If you have an alcoholic parent or a close relation with alcoholism, it’s highly likely that you might become an alcoholic/addict yourself, but not guaranteed; addiction zigzags through families taking down some but not others. It’s worth finding out if there are any addicts amongst your close relations because it very often remains hidden. Families don’t want to own up because it’s perceived as shameful to be an addict or to have a parent who was an addict. We need to stress that addiction is a deadly mental illness, and absolutely not a moral failing.

AB: Happily, recovery is now in the blood. Changing the legacy of our family with my own children is the most important thing that I can dare to hope.

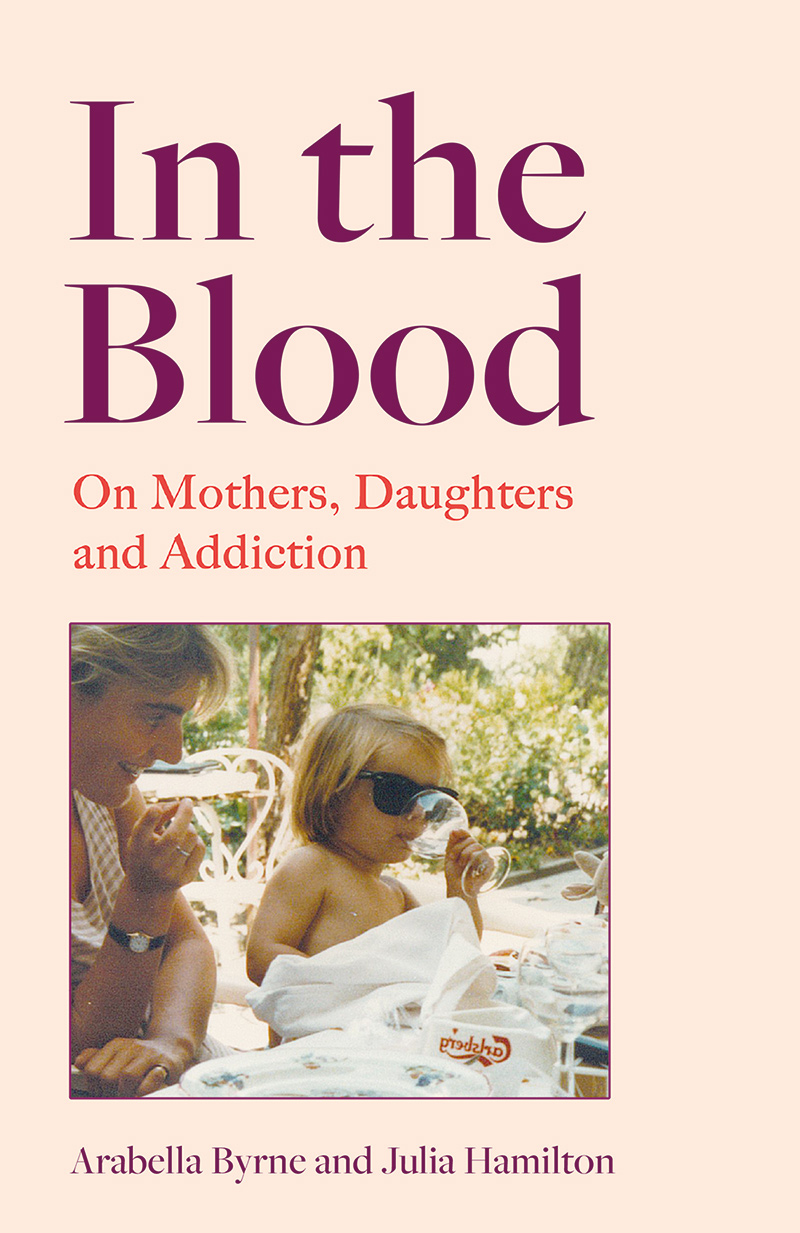

In the Blood: On Mothers, Daughters and Addiction by Arabella Byrne and Julia Hamilton is out now (HQ, £16.99). You can buy it from the Big Issue shop on bookshop.org, which helps to support Big Issue and independent bookshops. Addiction Awareness Week begins on 30 November.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more. This Christmas, you can make a lasting change on a vendor’s life. Buy a magazine from your local vendor in the street every week. If you can’t reach them, buy a Vendor Support Kit.