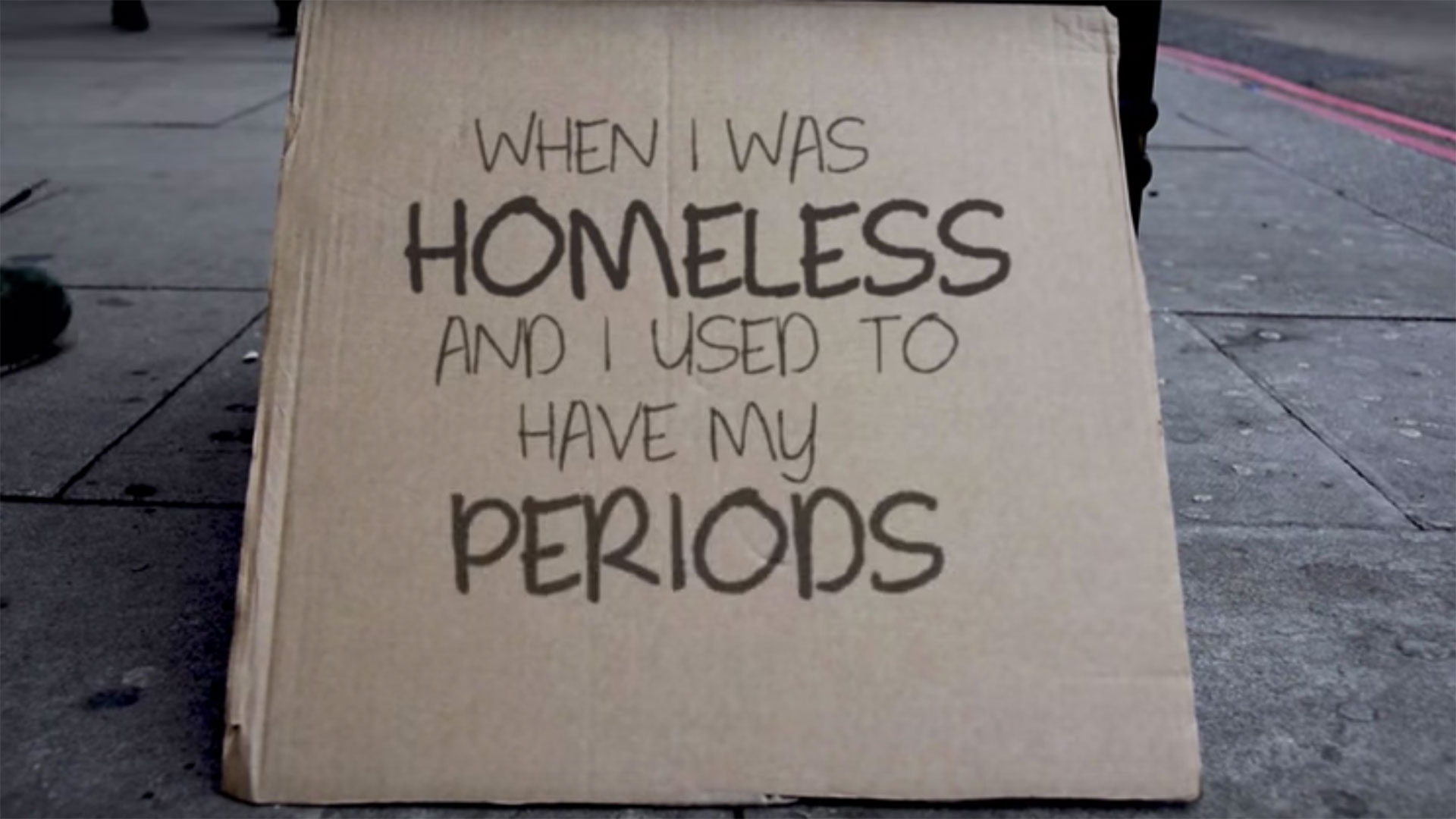

No one has really showed interest in the past in how women cope

Crisis estimates women make up 26 per cent of the known homeless population in England. In London it’s claimed one in 11 rough sleepers is female – a figure the charity deems “likely an underestimate”.

Last year, Spires worked with more than 250 women in London. “We speak with women every day who struggle with their periods,” Mhlophe says. “They can’t afford £3 or £4 on a packet of tampons. Many are forced to go to charity shops, and if there are bags [of rags] outside they might find something that is absorbent. For some that might be the only way to protect themselves.

“But we have no budget for this. We can’t give women a packet, only one. We are so strapped for money that we can’t afford to prioritise sanitary products. Every now and then we need to squeeze £10 or £20 to go and buy some, or perhaps a good Samaritan will donate a couple of packs. We never have them en masse, not like baked beans.”

On Mothers’ Day the Trussell Trust called on people to donate sanitary products to foodbanks, and Laura Coryton’s Stop Taxing Periods campaign, calling for the EU-imposed “non-essential luxury item” VAT classification on them to be dropped, smashed its 200,000 target. It was presented to George Osborne last month and last Thursday Ukip said it would end the five per cent levy.

Last week St Mungo’s Broadway’s staff, homeless clients and volunteers took a stand. “Our clients say managing your period on top of other issues can be an extra problem,” says Esther Sample, women’s strategy manager. “For women who are rough sleeping, or in more hidden homelessness situations, this can be even harder.”

Female Big Issue vendors explain there are different ways of coping. “You use whatever you can,” says one Edinburgh vendor. “Sometimes you use toilet roll in McDonalds or rip up a piece of paper. I’ve been to the hospital asking but you can’t always get there if you don’t have bus fares. It’s a health and hygiene issue, especially if you’ve not got access to a washing machine or showers.”

“I’ve got the [contraceptive] implant so luckily I’ve not had a period for a few years,” adds a second vendor, who has been homeless on and off since she was 16. “I still get bad period pains and I’ve sometimes asked homeless services for painkillers but they’re not allowed to give them out.”

Pushing the debate out in the open is crucial. “I didn’t think this would gather interest,” says Coryton, who has teamed up with The Homeless Period campaign. “No one wants to talk about tax. The one thing people like to talk about less than tax is periods. Now homelessness is involved, another grey area people don’t want to talk about. But that can only be a good thing. It’s vital we keep this conversation going and put pressure on the government and the EU.”

No one wants to talk about tax. The one thing people like to talk about less than tax is periods

The Homeless Period’s Bakhaty agrees: “In the short term it’s about raising awareness. In the medium term we are looking to get support from a manufacturer or retailer. The long-term ambition, which is where the petition comes in, is for the government to offer a grant to shelters or foodbanks so that sanitary care can be offered as an essential item.”

With parliament dissolved and no government to take her petition to, Bakhaty is calling on politicians to back the campaign. “There won’t be an overnight solution but I like to think there are politicians who feel strongly about this,” she says.

“It’s early days in trying to change what, in my mind, seems like a small thing but this could make a very big difference. Ultimately, this is about basic hygiene and dignity.”