Also if they study they come out of their alma mater bearing a mountain of debt on their shoulders that may well take a lifetime to pay off.

The debate was lively and vigorous in defence of passing on to the young and future generations some chance of getting the economic and social advantages had by the now older generation.

I though was having problems with the solutions being thrown up. They seemed to not take into account how we came to this situation where houses to buy or rent are beyond the reach of the young.

Surely you need a diagnosis before you have a prognosis. An understanding of cause and effect before you arrive at what needs to be done.

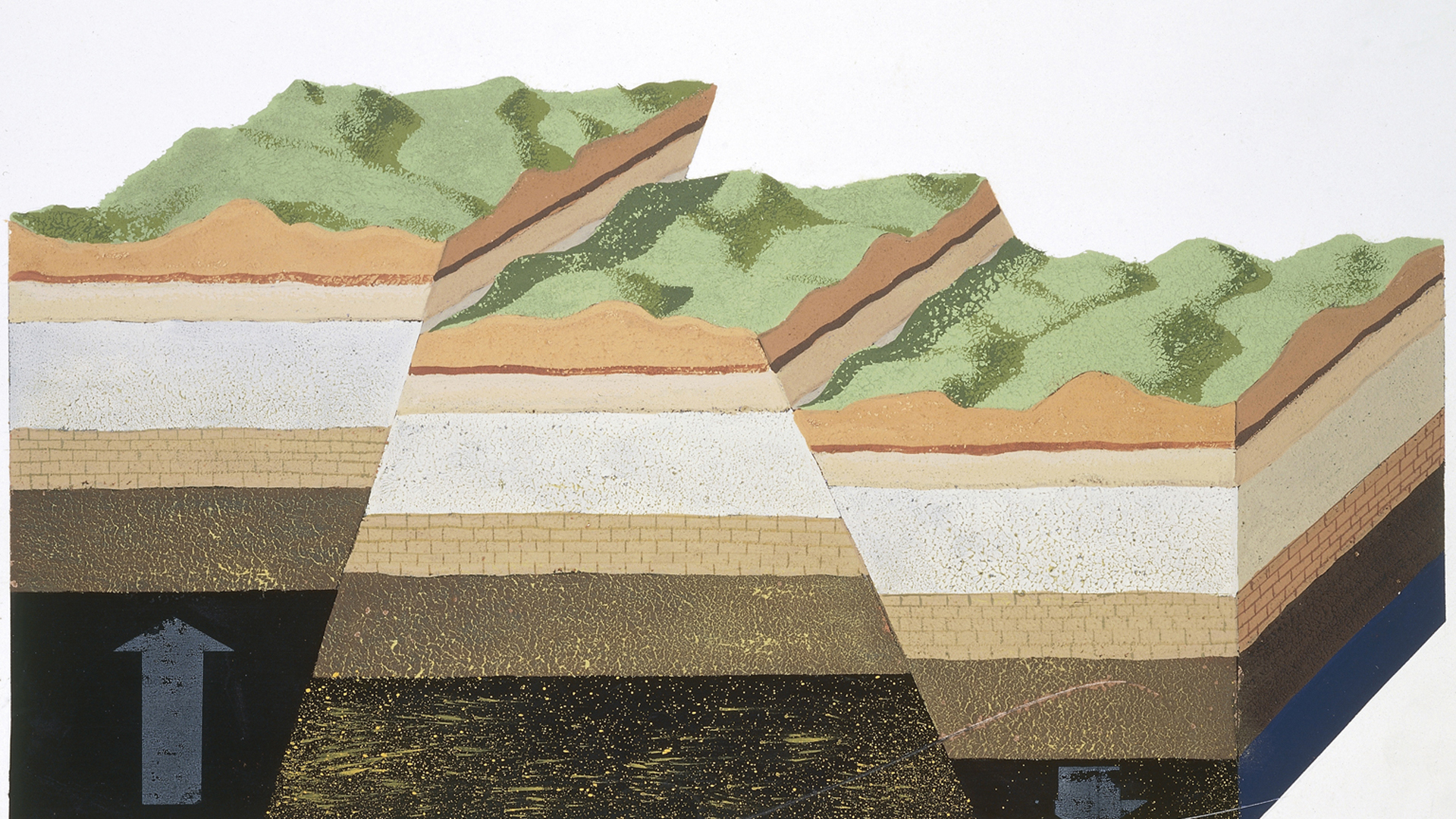

I tried my best in my allotted six minutes to deal with the underlying causes, the geology of the economic grounds we now walk on. Alas, as at times happens with me, I trip myself up with having too many ideas pressing at the same time into my mind. So my contribution on reflection was not as clear as I imagined it would be.

I described what to me seems to be one of the true geological causes, meaning the bedrock of the problem: and that is that we are a low-wage economy. That since the days of the Industrial Revolution investors in business have opted for investment in quick returns and low wages.

Investors have shied away from risk taking and complex industries that reward workers with skilled work and higher wages. Why invest in a new technology when you can make money out of making biscuits with thousands of jobs, for instance, with a very low wage and skill base?

‘Sliver Capitalism’, where you make very little from each worker, but if you employ enough of them then you get the fortunes the shareholders demand.

Low wages mean a low-investment economy. With that you also get low-wage education. And then on top of that you have low-wage health.

Lord Iveagh, of the Guinness family, paid the biggest death duty ever recorded when he passed in 1927. How did he make his money? In farthings. That is a quarter of an old penny, of which there were 240 in the pound.

He kept his wages at a reasonable level but he managed to make a sliver off every transaction. He did not have to invest in complex, risky adventures: just keep knocking out the beer.

So low wages paying for low paid, de-skilled jobs kept Great Britain clicking throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries.

But how do you get a bit of wealth under your belt? Well, the only way an ordinary person could do that, when not in a highly paid job, was to buy property. So from the 1930s onwards, like my uncle John Bird who was a plumber at Selfridges, you got a mortgage and you bought a little house. And then by the time you died you had a sizeable pot.

Low wages, low skills, but at least some people could buy cheap property. But with the growth of middle-class house-buying from the late 1960s, and then the loosening of credit under Thatcher in the 1980s, when council tenants were encouraged to buy their homes, property became wealth.

An interesting statistic demonstrates this: high street banks make around 80 per cent of their loans and transactions available for the buying and selling of property. Not for business development.

So we were fixated as a low-wage economy with getting our hands on some wealth, and property is almost the only way to achieve this.

Low wages mean a low-investment economy. With that you also get low-wage education. And then on top of that you have low-wage health.

That is, a health service that has to sponge up the consequences of a low-wage economy. You have people unable to eat good food, with almost half of hospital patients having nutritional issues. People who can’t rise out of poverty because their schooling prepares them for a low-wage job. Where one generation passes on to the next the educational desires of a low-wage worker.

Yet skilling people out of poverty is the only answer.

In Germany, high street banks deploy around 20 per cent of their funds to the buying and selling of property. The state invests heavily in new technology and businesses. Whereas in the UK the norm was to invest in the old industries that kept millions in work but were uneconomic.

Investing in new workers and new industry got Germany its prominence. Whereas the UK continued its flirtation with new technology but never made the big investments.

So the social geology of our intergenerational discord is based on our inability post-war to try and push the workforce up the skills register; get our schools producing people for jobs that were higher rather than lower paid. And get the government to invest in new industries and new technology.

I’m sure I’ve got much of the above skew-whiff. But I feel happier trying to fathom the true basis of our current plight over what is a bleak picture for the young and the unborn, for our future generations.

John Bird is the founder and editor in chief of The Big Issue.