This year he became chancellor of Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh and increasingly speaks out about human rights. Talking to The Big Issue from his home in Penicuik, he doesn’t take himself too seriously, even though the issues are incredibly serious. Most answers are followed by a chuckle, even if that’s because history, sometimes, seems so absurd.

Back in 2017, Palmer was asked by Edinburgh City Council to join a committee to review wording on a plaque commemorating Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville that stands atop a column in the centre of the city.

Palmer explains that there were plenty of discussions about new wording but no actual progress.

“The council were going to disband the committee because we were getting nowhere,” Palmer says. “Then George Floyd was killed. The leader of the council contacted me and said they were going to re-establish the committee. In five days we came to a new narrative. Five days.”

Dundas, if you didn’t know – and I certainly didn’t – was a politician, second only to Prime Minister Pitt, who in 1792 argued against the immediate abolition of the slave trade, ensuring the word “gradual” was added to William Wilberforce’s motion. I’ll let the new plaque, recently given planning permission by Edinburgh City Council, pick up the story:

“[Dundas] was instrumental in deferring the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade. As a result of this delay, more than half a million enslaved Africans crossed the Atlantic.”

Unlike the Colston-dunking protesters in Bristol, Palmer does not advocate removing statues of controversial figures. “If you remove the statue, you remove the deed,” he says.

Instead, the context is crucial. Palmer provides a mini-guided tour of St Andrew Square, where the Melville Monument stands central. “Across the road is the Dundas House – home of Sir Lawrence Dundas, a relative, which is the Royal Bank of Scotland head office.

“The statue in front of it, the Earl of Hopetoun, also a relative, helped end a slave revolution in Grenada. At the back of Dundas is the old headquarters of the British Linen Bank, responsible for selling clothes for slaves to wear. However, across the road is the birthplace of Sir Henry Brougham and he was a very distinguished abolitionist. So St Andrew Square has got a context of history. If you remove the statue, you destroy that.”

I tell Palmer that having walked across St Andrew Square a thousand times but I had never once thought or was told about whose statue was in the middle. Is it not relevant?

“That’s the point. It was so relevant. That’s why you were never told.”

In April, Palmer popped up in an unlikely place. He had taken his collection of Georgian silver sugar vessels on to the convivial Antiques Roadshow. The expert knew where they were made, what they were worth, but didn’t know what they represented.

Palmer’s collection came from the period of “gradual” abolition from the early 1790s. He said on the programme: “While slaves were working and dying, people in Britain were consuming the sugar in those bowls and with these tongs. To me these silver bowls tell us the sort of things we do in order to make money and to have a lifestyle we think we deserve.”

The expert was left speechless. In fact, they had to refilm the segment. “In the local supermarket and the post office ordinary people say to me that it made them realise for the first time the horrors of slavery,” Palmer says.

Is the collection on display? “I keep it in a Tesco bag.”

History is not black and white. In response to the new plaque at Dundas’ statue his seven-time great-grandson said: “Had it not been for Henry Dundas’ amendment to the legislation, the slave trade could have been about for decades to come.” In other words, it was gradual abolition or no abolition at all.

“How facile is that?” Palmer responds. “Some historians have got the nerve to say that because it was gradual abolition that makes him a gradual abolitionist.

“If you look at Dundas’ actions between 1792 and 1807 show me one thing he did to ensure abolition ended. What was he doing during that 15-year period? He was going to breed the slaves. He was buying slaves to fight in the British Army. And after they fought they were re-enslaved.”

Some historians think they’re doing people a favour by saying you don’t have to accept any responsibilities

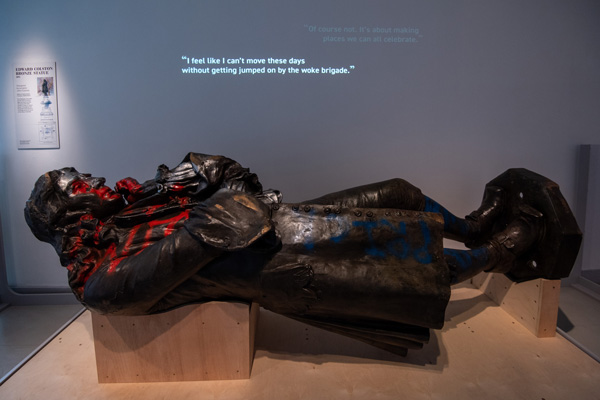

Other cities across the UK and wider world are taking action. The fished-out Colston statue was put on display in Bristol’s M Shed museum this month, in correct context with placards from the protest. Visitors can complete a survey to decide what should happen to it next. The city’s Colston Hall has been renamed the Bristol Beacon.

Edinburgh, with the help of Palmer, is doing more than most. Officials from Canada and Australia have been in touch, as well as the Jamaican Ministry of Culture. But this great city of enlightenment, is also responsible for the darkest of days. Up on the Royal Mile sits David Hume. He is, Palmer states, at the root of racist attitudes.

“In 1753 he said: ‘Negroes are naturally inferior to whites.’ Then the philosopher Kant picks tacks on colour and race. So the Negro race is inferior to the white race. That’s the beginning of racism we’ve got today. That’s what killed Floyd.”

There’s no way to talk about controversial issues without being controversial. Is there a way to prevent debate becoming a reactionary battle when it should really be a process of understanding our history?

“That sounds very commendable,” Palmer deadpans, before sharing a lesson from his lectures. “Two planes on the runway. One is built by a guy who is of the opinion he can build a plane. The other is built by a guy whose opinion is taken from evidence. Which one would you fly?”

We live in a world where people seem like they’ll do anything rather than admit their beliefs may be wrong. Insert questionable vote result of your choice here.

“You can have opinions and beliefs that are perfectly respectable,” Palmer says. “The whole idea of having this general discussion is fine. But sometimes that is a ruse for something to get nowhere.”

Head over to Palmer’s Twitter profile and see him tackle trolls who try to pick apart his arguments. Some historians among them.

“The point is to denigrate me and say to the public: don’t listen to him because he’s not an expert. I’ve got a Doctor of Science in research. A lot of people think research is just looking up a book. Research is about asking questions and answering them with experimentation.

“Some historians think they’re doing people a favour by saying you don’t have to accept any responsibilities. Scottish people were involved in slavery – they owned 30 per cent of slave plantations in Jamaica – but a big person is one that will put their hands up and says it was me. But what can we do to address it?

“We cannot change the past but we can change the consequences of the past, such as racism, for the better, through education.”

Palmer experiences first-hand the changes that this can make.

“You won’t look at me as an incomer. That’s what I used to be called in the ’60s – an incomer. Jamaica has been part of the English/British setup since 1655. People now see me not as an incomer but somebody who is part of this culture.”