They call Australia ‘the lucky country’, and boy is it: spectacular beaches, incredible landscapes, minerals for mining, good soil for farming, space for grazing, a laidback outdoors lifestyle, and some of the most liveable cities in the world. I write from experience – in 2008 my wife and I emptied our house into a shipping container and put ourselves on a plane to Melbourne, intending to stay perhaps a year but ending up staying six. Even then we were reluctant to leave. We felt like we were the lucky ones for having lived there so long, and may yet move back again in the future some time.

But I very quickly became aware how little I knew of Australia’s history, or of the long legacy that British colonialism had left behind. It wasn’t something we were ever taught in school, and current Australian politics were rarely covered on British news: the same old tropes of long-ago convict settlements and long-held sporting rivalries were about as far as it went.

Now here it was playing out in front of me: prime minister Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations; the street names and statues of pioneers; the Eureka Stockade memorial; the giant Ned Kelly sculpture in Glenrowan; the casual everyday racism; the abuse frequently hurled at indigenous football stars.

The story of the American West has been told a thousand times, but as I read about Australian history, and particularly the 19th-century frontier, what surprised me more than anything were not just the many parallels with the old ‘Wild West’ myth but the fact that the Australian version was so little known. The country has been through eras of epic exploration, gold rushes, uprisings and violent conflict on a massive scale, whose stories are easily the equal of their more famous counterpart, and yet have remained –with a few exceptions – largely untold.

There is a much darker side to British-Australian history

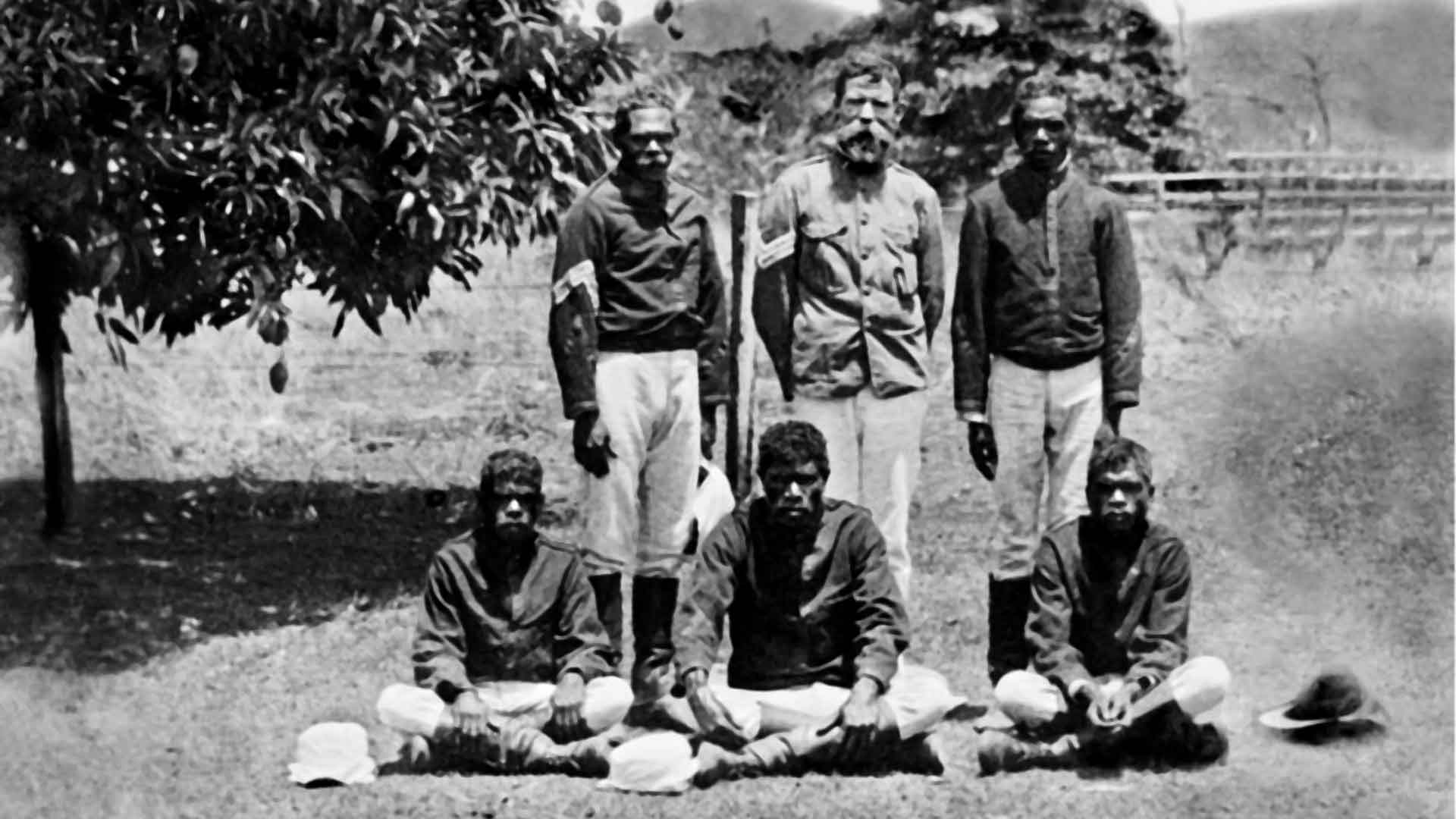

And perhaps with good reason. For all the accounts of noble pioneers and the ill-fated heroism of men like Burke and Wills, there is a much darker side to British-Australian history, no better exemplified than by the Queensland Native Police: an official arm of colonial law enforcement that patrolled the19th-century frontier, operating on the borderlands of white settlement and ‘dispersing’ indigenous Australians however and whenever they saw fit.

Yet this wasn’t some militia: the Native Police, as with its counterparts in other British colonies, was established with the same veneer of propriety as any police force. Overseen by a commissioner, each patrol would comprise a white officer, designated by rank, and a small group of mounted Aboriginal troopers, often recruited from faraway lands. They were stationed at barracks, were well armed and well funded, and, in theory at least, subject to a precise list of operational rules.