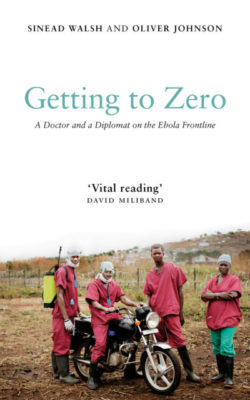

Dr Oliver Johnson

My time in Sierra Leone didn’t begin with the Ebola outbreak, as it did for so many international responders, but as a medical student several years before. Having fallen in love with the small and vibrant west African nation, I had returned after graduating to set up a partnership between King’s College London and Connaught Hospital, the main hospital of Freetown, Sierra Leone’s capital city.

Like the rest of the country’s health workers, I wasn’t at all prepared for an outbreak of this deadly and mysterious viral haemorrhagic fever. What first seemed like a remote curiosity rapidly transformed into an imminent threat, as the disease marched steadily towards Freetown from the east of the country, after crossing the border from neighbouring Guinea.

Freetown had become my home

Each day, more stories came in of Ebola decimating whole families and villages. It proved particularly deadly to our fellow health workers, who lacked the resources and the training to protect themselves. But I never felt any doubt about staying and standing shoulder-to-shoulder with colleagues at the hospital. Freetown had become my home.

Up to that point, I hadn’t been doing clinical work in Sierra Leone, as my role focused on policy and management. That all changed one Saturday in July 2014 when I stumbled across a desperate situation inside the hospital’s main gates, where a collapsed Ebola patient was in desperate need of care. So I suited up in a claustrophobic white protective suit for the first time, my face smothered by the goggles and mask under the sweltering tropical sun. Over the next several months, alongside my work to set up a Freetown command centre and advise on the British response, I would help care for hundreds of Ebola patients in our small and dilapidated unit at the hospital, faced with growing queues of the sick and the dying outside the main gates and constant crises that ranged from protests to water shortages.

The challenge we faced was unprecedented and none of us knew how bad it might get.