One of the things I love about cities is their air of mystery: that sense that behind the next corner you might find a hidden street, an unexpected alleyway, a specialist supermarket for a local diaspora or an obscure museum. I love, too, the accompanying gift of anonymity that comes with big city living, that you can fade into the background, that you can walk just 15 minutes in any direction and disappear.

But there’s a sinister side to a city’s vastness, too – not everyone who disappears wants to, and not every surprise lurking around the next corner is a happy one.

A big city’s complexity is both a gift to novelists and a trap. In crafting a satisfying novel, with a beginning, middle and end, writers often have to flatten the metropolis in order to service the plot. When writers succeed, it is often by leaning into one of the hidden virtues of a big city; that every large city is in fact a series of small villages huddling together for warmth, whether those villages be geographic neighbourhoods, particular subcultures or diaspora communities.

Those books which aim to do more than cover one of a city’s hidden villages tend to end up as sprawling messes. Linda Grant’s A Stranger City’s great triumph is that it covers the whole city, and remarkably so.

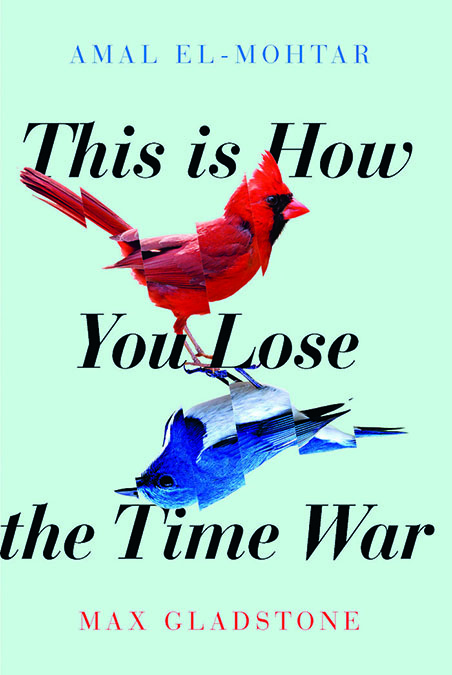

As a thoroughly modern novel, in which contemporary politics are never far away, and Brexit, though never specifically named, casts a menacing, looming presence over the novel and its characters, it can’t use the trappings of a specific genre to service the story it wants to tell, as This Is How You Lose the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone does.

El-Mohtar and Gladstone’s story is this: two spies in the service of two warring nations trade letters as they travel backwards and forwards in time, battling one another and gradually falling in love. It sounds complex but the execution is engagingly simple. The intergalactic and historic sweep – our two spies play off against each other in the far future, exchange book recommendations in a 18th century teahouse and write letters to one another in the Mongol Empire – services rather than overwhelms what is in essence a story about falling in love under a repressive dictatorship.