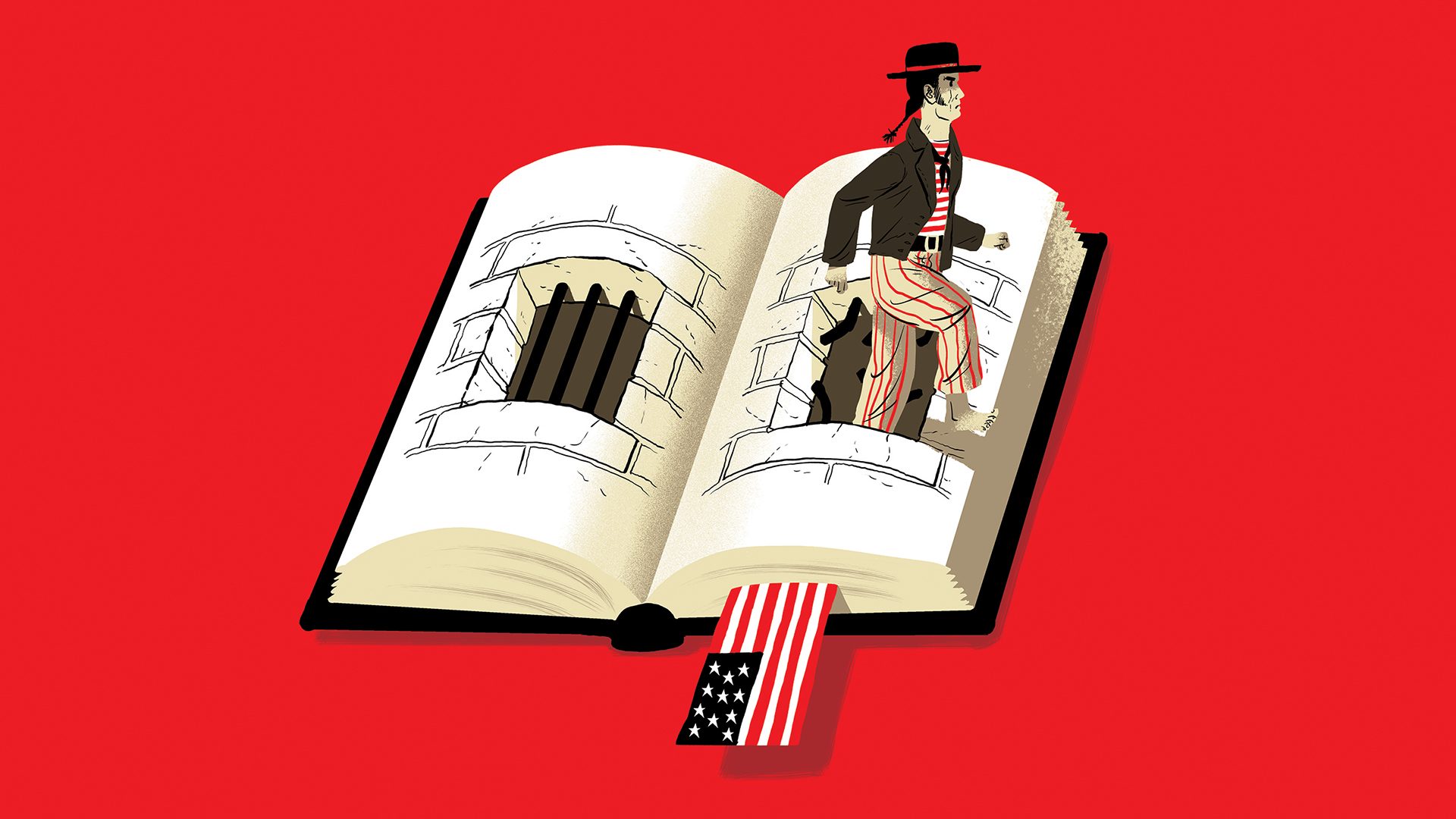

In the summer of 2017, I was on holiday with my family in Devon when we came across Dartmoor prison. I knew it had held some notorious murderers behind its walls, along with a slew of political prisoners (from Irish Republicans to conscientious objectors). But I didn’t know it had been built in 1809 to hold French PoWs from the Napoleonic wars. More embarrassingly, since I teach American history, I had no idea that Dartmoor was home to 6,500 American prisoners during the War of 1812.

If Dartmoor had been located in the US, it would have been the 20th-largest city. But here it was, perched on moorland in the middle of nowhere, a story of American suffering in Britain that was totally alien to me. When I got home I resolved to read some books about it. When I discovered that those books didn’t exist, I decided to write one myself.

Dartmoor was a truly strange place. For one thing, it was supposed to be a temporary prison, designed only to incarcerate captives until the war ended, and yet it had been constructed out of granite (In 1806, when construction began, Britain’s supplies of timber were routed almost entirely to the Royal Navy.) Then there was the layout of the prison. Dartmoor had seven long blocks with three floors each; there were no cells, and although prisoners were confined each night to their particular block they were allowed to wander the prison during the day. The French and Americans weren’t criminals, after all, and the prison authorities offered them plenty of latitude, providing they didn’t try to scale the huge walls.

This arrangement gave prisoners space to express themselves, even if Dartmoor’s cold and bleakness were hard to shrug off – not to mention the diseases that periodically ripped through the prison. PoWs were allowed to keep any money they’d had with them when captured. The better off among them asked their relatives to send more, and every prisoner received an allowance from the US government. With all this cash there was plenty of scope for commerce, gambling and an entire service industry within the prison.

The Americans taught each other boxing, dancing, fencing, navigation, foreign languages and more; one prisoner said that Dartmoor was like a university with seven colleges. The British allowed local traders to enter the prison every morning to sell or smuggle food, tobacco and any number of contraband items. The American prisoners got their hands on alcohol, newspapers and shivs; the French somehow secured a roulette wheel and a collection of theatrical scenery. When they were released in May 1814, the French prisoners sold their loot to the Americans and Dartmoor’s casino and theatre were placed under new management. Of course prisoners tried to escape – by bribing the guards, initially, but then by scaling the walls and by digging tunnels from the blocks to the moor beyond the prison. I won’t spoil the stories of what happened, but for me the prison breaks alone made this a story worth telling.

Then there were the things that the prisoners did to each other: the suspicions and accusations, the beatings (and worse) that scarred them as their plight became more desperate. Astonishingly, after just a few months in Dartmoor the white American prisoners asked to be separated from their Black compatriots, and the British authorities granted their request. Dartmoor became the first racially segregated prison in American history, though the story doesn’t end there. After the Black prisoners were given a block to themselves, ordinary white prisoners flocked to its shops, schools, church and theatre. The leaders of the white prisoner community had insisted to the British that they couldn’t live alongside Black people; rank-and-file white prisoners proved that the opposite was true. Dartmoor became a striking example of racial coexistence in an era in which socialising across the colour line was largely forbidden. But when the war was over, the story simply vanished from view.