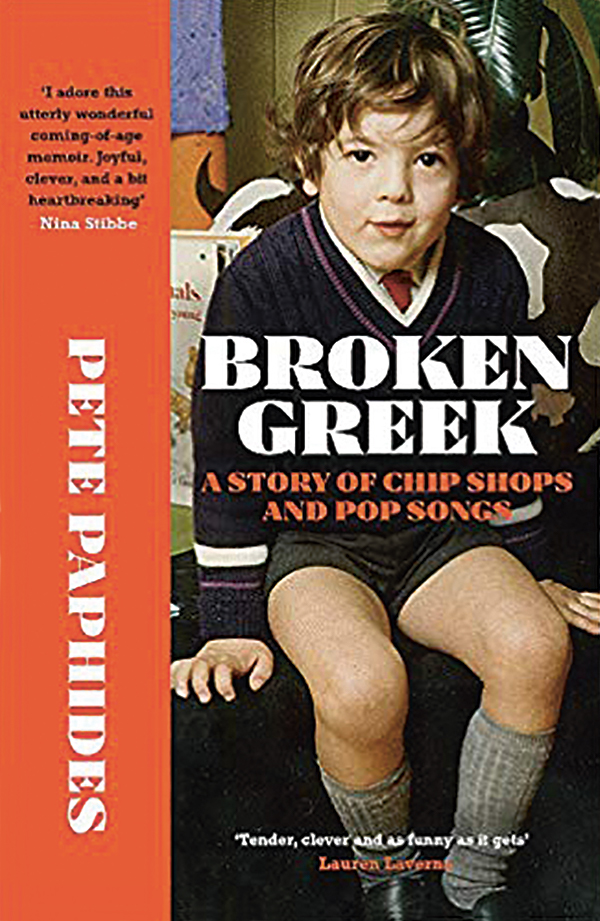

The cover image of Pete Paphides’ boyhood memoir is perfectly chosen. It is an impossibly cute picture of the author at the age of five: curly moptop, big brown eyes, chubby cheeks, grey school shorts and long socks. Most of us can locate a similar photo of ourselves, taken in that short period before life clamped its crocodile jaws around us and started shaking.

Appropriately, then, there is something of the everyman in Broken Greek. Many of the challenges faced by young Paphides – building and maintaining friendships, figuring out his sexuality, developing cultural tastes, trying to work out how to be cool and to avoid getting beaten up by the local toughs – are standard childhood fare. It is in the telling that the author elevates his story to something rather beautiful.

Paphides is a music writer and DJ (he is also married to the writer Caitlin Moran). I experienced the same feeling reading this book as I do when listening to his show on Soho Radio – you are in the happy, rewarding presence of an irrepressible enthusiast. He exudes a stubborn naivety, an insistence on locating the positive, that stands out in our era of social media snark and drive-by brutality.

Growing up in Birmingham with Greek-Cypriot immigrant parents, Paphides is caught between two cultures. His parents have a relentlessly attritional existence running a chip shop, while trying and largely failing to assimilate to life in the UK. His father, in particular, an almost stereotypically repressed Mediterranean male, is desperate to return to Cyprus. Pete, feeling more British than Greek, desperately searches for an identity that accommodates both his own emerging, modern desires and those of his traditionalist parents.

Broken Greek is charming, funny and will be hugely relatable to anyone who grew up in the Seventies and Eighties. “That’s a lot of pockets,” says Pete’s mum when his quiet friend Edward Osborne turns up on their doorstep in full Sid Vicious get-up. “They’re bondage trousers, Mrs Paphides. I’m a punk now,” says Edward respectfully. On Hogmanay 1979, Pete and his brother Aki watch Cliff Richard perform his hit Devil Woman, his “signature late Seventies/early Eighties ‘dance’ that of a man carefully emerging through a foggy clearing at night in a glade where a puma has been reportedly sighted”.

The need to get the “right” schoolbag and trainers, avoiding the cheap knock-offs that will lead to the inevitable playground slagging, remains all too fresh in the memory. The book is full of these familiar touchstones. And throughout, you root for kind, uncertain, scared but spirited little Pete, knowing that his good-hearted enthusiasm will in time enable him to fix what is broken.