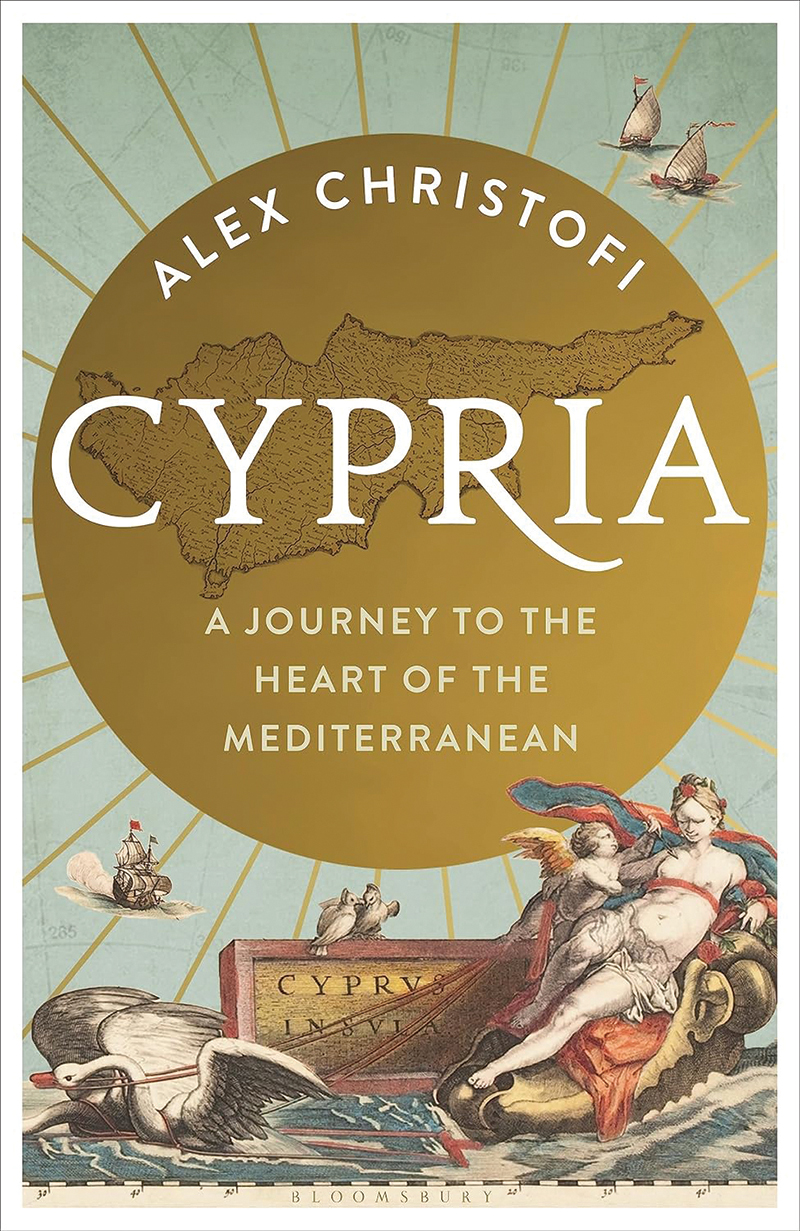

Fifty years ago this summer, the island of Cyprus was divided by conflict. The crisis began on 15 July 1974, when soldiers backed by the Greek military dictatorship staged a coup, turning up in tanks to depose the democratically elected President of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios III. In the ensuing chaos, the Turkish army invaded from the north. A third of the population had to flee their homes, and still haven’t returned. There is still no official peace agreement, only a ceasefire.

This state of division feels like a sign of the times we are living through now, with bitter conflicts playing out in eastern Europe and the Levant. In fact, Cyprus has always been a microcosm for whatever is happening across the region, standing as it does at the crossroads of three continents. Through Cyprus you can take in the whole history of the Mediterranean: the rise and fall of great powers, the vast trading networks that link Europe with Asia, and the birth of the modern age.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

Among early civilisations, Cyprus was responsible for a string of firsts. The dry island had the world’s first water wells, the first pet cat (take that Egypt!) and the first recorded sea battle (against the Hittites of Anatolia). It was Cypriots who first developed the smelting that ushered in the Iron Age, and some scholars think it was on Cyprus that the European alphabet was created, as Greeks mingled freely with literate Phoenicians. Later, Cyprus took part in the famous Persian Wars, gave Alexander the Great his favourite sword and hosted some of the first Christians. (You can still visit the tomb of Lazarus, who moved to Larnaca after Jesus raised him from the dead.)

On the very edge of the Byzantine empire, Cyprus already had Muslim influence and inhabitants just one generation after the death of the Prophet Muhammed. Richard the Lionheart conquered the island almost by accident on his way to fight for Jerusalem, and for centuries it became a Crusader stronghold. Then, the rising merchant empire of Venice took control, but not for long: the Ottomans besieged the city of Famagusta for almost a whole year. The fall of Famagusta prompted the Battle of Lepanto, an epic sea battle between the Ottomans and the Christian Holy League, where the Spanish writer Cervantes lost the use of his left hand “for the greater glory of [his] right”.

- Top 5 books about Greek mythology, chosen by Jennifer Saint

- This tiny Greek island now has zero waste – leading the way for the rest of the world

For the past 150 years, Cyprus’s fate has been tied up with the British Empire and its interests in the Middle East. Prime minister Benjamin Disraeli made a deal in 1878 to protect the Ottomans from Russia in exchange for Cyprus. Since then, it has been a key military base, protecting Suez and, later, hosting nuclear bombers that could reach deep into Soviet territory. The island was granted independence after a five-year guerrilla war in the ’50s, but the administration kept 3% of the island as ‘sovereign territory’, meaning there are places on the island where you are technically in Britain. These days, if British aid is to be transported to Gaza, or an Iranian drone shot down over Israel, the base of operations is Cyprus, which acts like “an unsinkable aircraft carrier” in the words of the old Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev.