If you’re feeling disillusioned about democracy, you’re not alone. We are suffering from an unusual malady: democratic fatigue syndrome. But unlike many illnesses, this one isn’t so hard to explain.

The past two decades have seen plummeting trust in democratic institutions and political parties on a global scale. It’s not surprising: they’ve been doing a poor job at delivering the basics, from secure employment and affordable housing to keeping food and energy prices in check.

The result is millions of people turning to support anti-system leaders on the far-right, from Trump to Farage to a swathe of European populists who are now starting to win elections. Today only 34 out of 179 countries in the world can be classified as ‘liberal democracies’ – the lowest number for 30 years.

When moderate politicians get into power, they not only get caught in the typical scandals of the political class – like Keir Starmer’s recent freebie freefall – but seem to be lacking the big ideas to deal with the urgent issues of our time, from the climate crisis to bringing AI under control.

Our current system of representative democracy – where we select MPs to rule on our behalf every few years – is failing. But are there any other options? Winston Churchill declared that “democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the other forms that have been tried from time to time”.

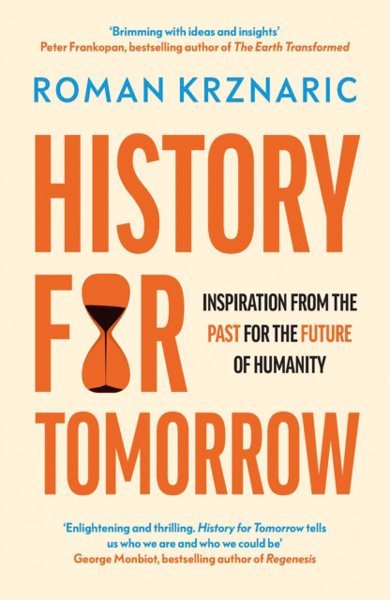

Well, he was wrong. As I argue in my new book, History for Tomorrow, history offers a surprising number of alternatives to representative government. British colonialists stumbled upon one of them when they entered the lands of Igbo communities in Nigeria in the 19th century. They were looking for chiefs or leaders but couldn’t find any. Igbo people operated a form of ‘assembly government’, where most decisions were made communally at the local level in village councils (where all men and women could usually participate).