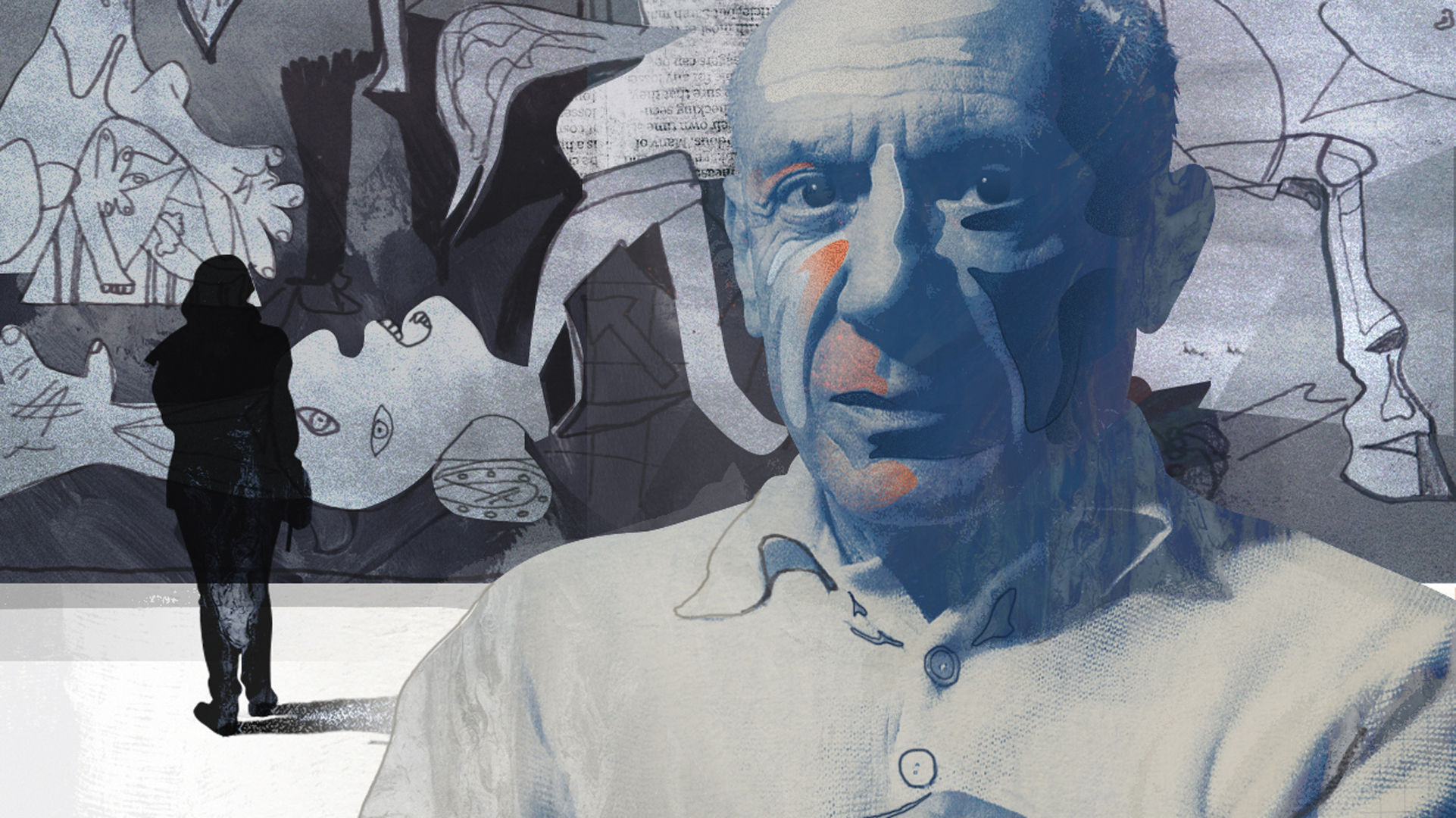

Despite the flood of visual stimuli we are subjected to every day, certain images persist, losing none of their power to move and engage us. Pablo Picasso’s Guernica is one of these.

When first invited to write a book about it I was initially a little reluctant: after all some of the greatest art historians of recent times had done so already and their conclusions contradict each other in ways that only add to its mystery. However I soon found myself gripped by its story, which has strong resonances with our own times.

Picasso was inspired to paint Guernica by a specific event during the Spanish Civil War, the carpet-bombing of the undefended Basque town of Gernika on April 26, 1937 by the Condor Legion of the German Luftwaffe. However, the painting includes neither planes nor combatants. Instead, its living subjects, four women and three animals, share the canvas with a dead baby and a fallen soldier. The space they occupy is neither clearly inside nor outside. Nothing ties the painting’s content to a specific place or date – we could be looking at any time in history; the soldier’s dismembered arm still clutches a broken sword.

For him, art was a spontaneous process rather than something summoned to order.

Picasso had lived in Paris since 1904, but events in Spain disturbed him deeply. The French press carried shocking descriptions of civilian casualties during the bombing of Madrid. His mother and other family members were still living in Barcelona; and in January 1937 Picasso’s birthplace, Malaga, fell to Franco’s troops, his childhood home transformed into a tableau of death and devastation. Yet when that month he was asked to paint a picture for the Pavilion of the Spanish Republic in the World Fair that was to open in Paris in the summer, he agreed reluctantly. He hated commissions: for him, art was a spontaneous process rather than something summoned to order.

For months, he struggled to find a subject. Then on Tuesday April 27, the Spanish poet Juan Larrea came to find him with news of the bombing of Gernika, certain it was the subject he’d been searching for. That Saturday, Picasso made the first sketches for Guernica; some five weeks later the painting was delivered to the Pavilion.

Guernica divided opinion on its first appearance. While some declared it a work of genius, the film director Luis Bunuel, who helped hang it, said he would have been happy to blow it up; Basque painter José María de Ucelay went further, declaring it nothing but “7 x 3 metres of pornography, shitting on Gernika, on Euskadi (the Basque Country), on everything”. Anthony Blunt, writing in The Spectator, called it the “private brainstorm” of an artist who understood nothing of its political significance.