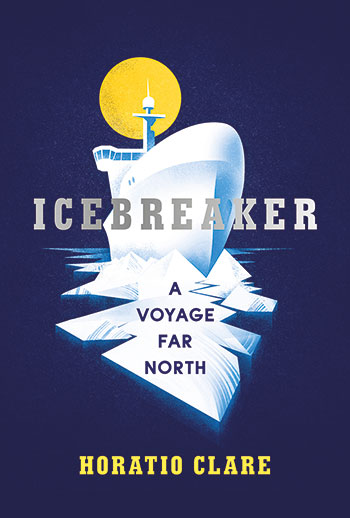

It feels wrong to describe Horatio Clare’s Icebreaker: A Voyage Far North as ‘travel writing’, though this is the popular term for his work. He certainly goes on journeys – on a container vessel around the world in 2014’s award winning Down to the Sea in Ships, and tracking down one of the world’s rarest birds in 2015’s Orison for a Curlew (possibly the most elegant title for any book in the last decade). But if one is looking for a guide to holidaying in foreign parts, with advice on language quirks and appropriate footwear, Clare is not your man.

You’ll learn about the history and geography of the elusive, slippery country of Finland in this book, but the thing you’ll remember most is the delicious feeling of shivering in a magic kingdom of ‘crystalline brilliance in the moonless darkness’. Clare’s prose is so brilliantly evocative and so rich with awe, this book could sit as comfortably next to Grimm’s fairytales as it does in the travel section.

Finland, celebrating a century of independence this year, still suffers from a preponderance of cliches regarding its ‘agricultural’ diet, challenging climate and steely air of desolation. But Clare positively raves about the nation’s outstanding education system, progressive politics and socially responsible economy. He finds his reindeer dinner ‘delicious’ and is overwhelmed by a break in the grey clouds revealing ‘a gold-scaled chalcedony blue like the promise of adventure’.

With an elegiac Keatsian sensibility Clare depicts ‘the making and melting of ice’ seductively

He is, in short, a romantic and optimist, traits he shares with fellow friend of the earth and logophile Robert Macfarlane (who will surely whoop with delight to hear that the Finns have a word – kalsarikännit – for getting ‘drunk at home in your underwear’). He also has an anthropologist’s insight into the people around him, whom he watches through the gloom like a bat hawk, noticing the finest of flinches and sparks.

The real magic begins when Clare gets out into the snow and experiences the ‘all-changing miracle of its deepening’, accompanied by an abrupt coldness ‘like icy hands fishing for your ribs.’ Then it’s on to the good ship Otso, and off to the frozen, Arctic-nudging Bay of Bothnia, a place which ‘has no distances’, only hours, and speeds of wind and ice.

Clare’s skill for immersing his readers in time and place – or rather, transporting them to a place somehow beyond both – is quite magnificent. With an elegiac Keatsian sensibility, he depicts ‘the making and melting of ice’ so seductively that reaching the end of this wonderful book feels like stepping out of a Finnish sauna into a cold shower.