I was one of two pupils from my primary school class who passed the 11 plus and went to St Malachy’s college in Belfast. My biggest passion at school was football. My mother always worried about me getting into bad company but at school I was in good company. I had great friends, and we were all interested in things. One friend loved opera; he played me Caruso and infected me with his love of music. Another loved books. We had a skiffle group – I played the tea chest. We spent most of the time laughing. My friends could make me laugh till I was sliding down the wall.

We lived in a big Victorian house on the Antrim Road. After the war my father brought my grandmother, grandfather and my great aunt to live with us, so I was brought up around old people. And I loved it, drifting off to sleep listening to them talk. There was a bookcase with a glass front, but it was mostly religious books. I wasn’t as interested in books then. I liked comics – The Wizard, Roy of the Rovers. I did read Just William and Biggles. Then one day, when I was about 16, my friend gave me my first grown-up novel and I made the leap from Biggles to Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. I was knocked out by it.

I was 12 when the big bad thing happened. My father died of cancer. That really upset the household to say the least. I felt his absence in every way. I never got to have an adult conversation with him. But the grannies and grandas and aunts were some kind of substitute. And across the street the other side of the family, the MacLavertys, including my aunt Sissy, who was known for making three types of bread a day – wheaten, gingerbread and soda bread. That was a great house I could go over to 10 times a day. So gradually the pain of my father’s death faded. But for many years I dreamt of him coming back.

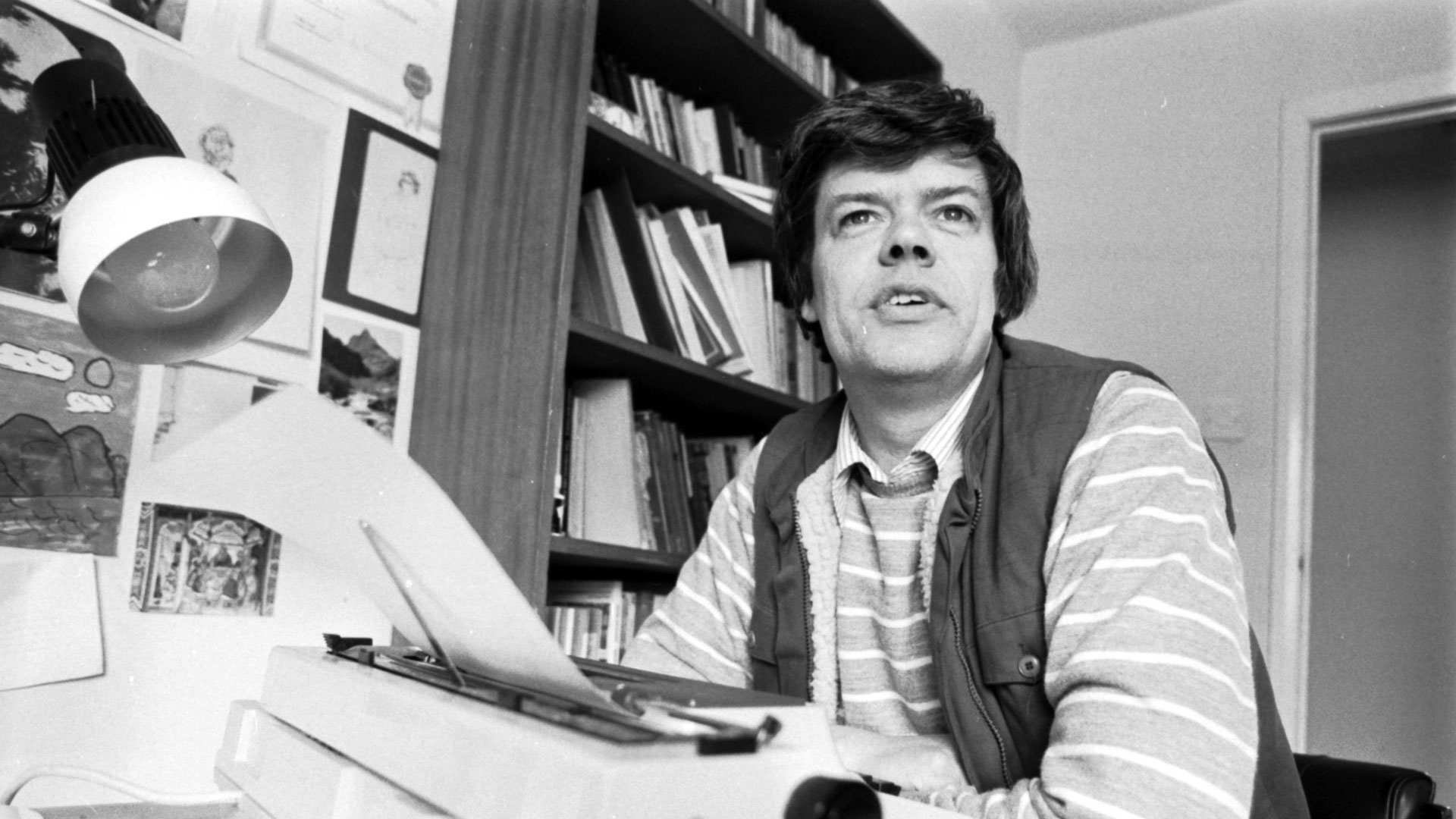

At 16 I started to write very bad poems. We had an English teacher who introduced us to Gerard Manley Hopkins, this cool priest who wrote really rock poems. I started putting down words. I thought they were good and thank God nobody told me they were terrible. Then I discovered the stories of Michael McLaverty and he became a kind of hero of mine. Gradually the poems stopped and the paragraphs started.

Your feelings about being Catholic are different when your life depends on it

In terms of religion, at 16 I still had a straight-forward belief. And terror. The whole ethos of hell and damnation, and suffering for all eternity. I believed it all until about my mid-twenties. Now I’d tell my 16-year-old self: don’t believe a word of it. Take what is good out of religion. Stained-glass windows. Great music. Goodness and kindness. The anti-racism, churches with people of every colour in them, all over the world. But… it doesn’t exist.

Your relationship with religion is complicated in Northern Ireland. Your feelings about being Catholic are different when your life depends on it. You start chatting to someone in a pub and a whole dance begins. You have to work out what side that person is on because damage can be done. You do it throughconversation – are they interested in Gaelic football or rugby? What football team do they support? It’s all done politely. But if you get it wrong you might get a kicking or even a bullet in your head.