I remember it clearly: lying on the sofa in a patch of sunlight at the end of lockdown, and reading Noël Coward’s early play Hay Fever. I had been struggling for over a year not only with closed libraries, but with the prospect of working on a new biography of Noël Coward, writer of comedies, composer of songs, director of films, and epitome of 1920s high life.

He had been suggested to me as a subject. There was a new archive, never before seen, and I said yes, because you don’t say no. But then I spent a grumpy year not sure I had done the right thing. Surely Noël Coward was a bit old-fashioned for me, and he had been written about at length anyway. People asked me to my face: “Why him? Surely he’s a bit dated now? And have you heard the anecdote about…?” (I usually had.) And then I read Hay Fever in the spring sunshine, and it seemed to me one of the most perfect comedies ever written. Surely the mind that dreamed it up was one worth the bother of writing about.

People thought they knew the story. There was the god-given talent for comic dialogue. There was The Vortex, a scandalous script about drug addiction and closeted homosexuality that made Coward, at the age of 25, one of the most famous men in the country. There were the films: Brief Encounter,

In Which We Serve. The immortal comedies: Present Laughter, about the vain actor Garry Essendine, or Private Lives, in which a divorced couple reunites by chance on adjacent balconies of a French hotel. And Blithe Spirit, about a man torn between his first wife and his second, the only hitch being that the first happens to be dead, and has returned from the underworld to haunt his Kent drawing-room.

Your support changes lives. Find out how you can help us help more people by signing up for a subscription

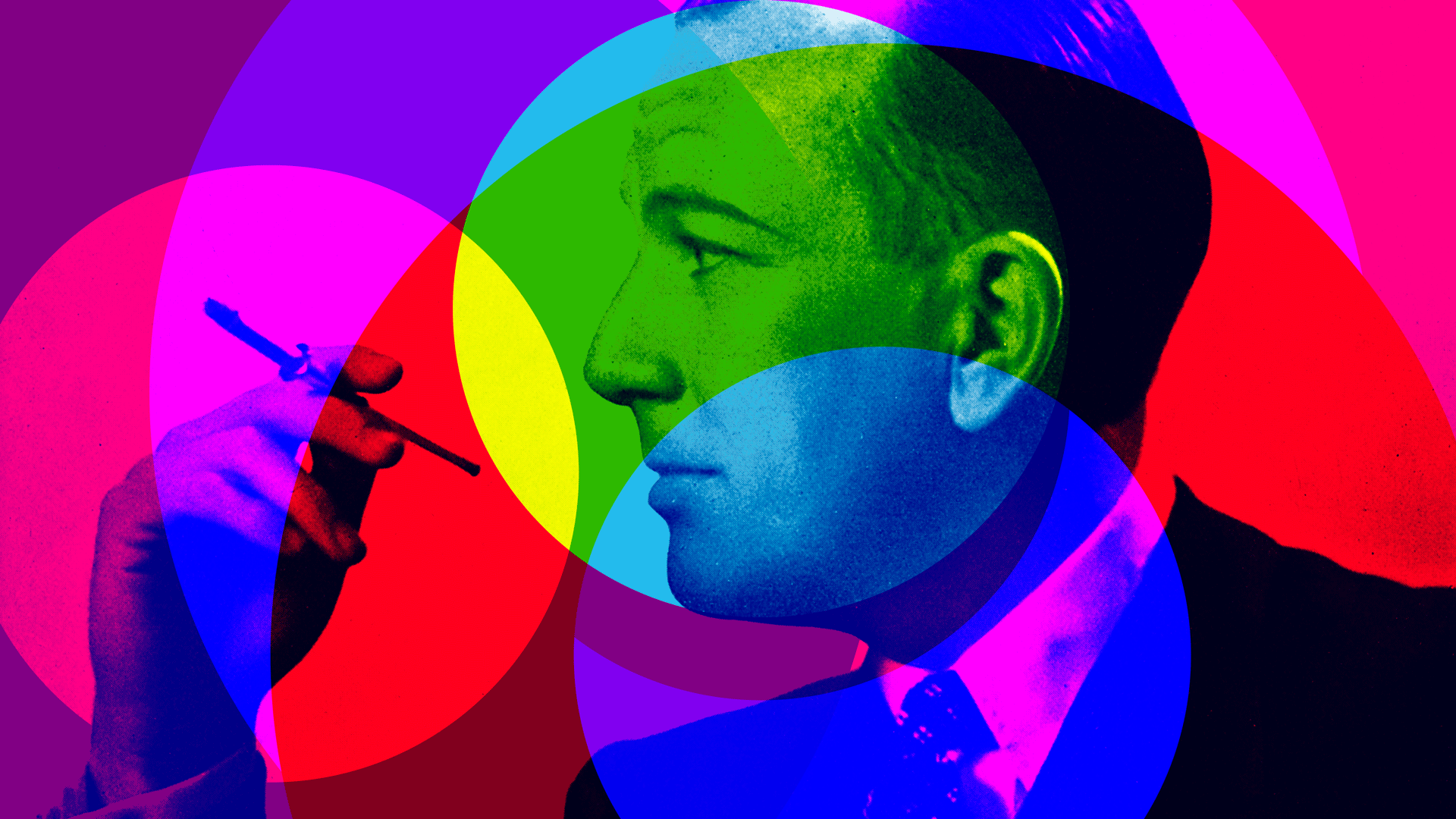

But then I started really to read Coward, and read, and read (his collected plays span nine volumes, to say nothing of the lyrics, the diaries, the letters, the poetry). It’s still the case that few people know the side of him that created Post-Mortem, his 1930 play set in the trenches that received its world premiere in a German prisoner-of-war camp. Or that aged 18 he wrote a script about drugs, too scandalous ever to be staged, called The Dope Cure. Or that, beneath the carefully cultivated appearance of a stylish society man (dressing-gown, cigarette holder, slick hair) there lay an unhappy soul, who had a nervous breakdown in an army training camp, narrowly avoiding being sent to the Front, and who thought that he did not know how to love.

By the time I was handed his unexpurgated diaries, charting the strange life of espionage and entertainment that he led during the Second World War, the biography started to write itself. Here were never-before-seen accounts of his meetings with President Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, for whom he became a strange go-between passing messages back and forth. New reports of his work for William Stephenson, greatest spymaster of the conflict, and of Coward’s secret life in Paris before the bombs started to fall, where he witnessed Coco Chanel walking into an air-raid shelter followed by a maid carrying a gas mask on a velvet cushion.