It’s well understood that prisoners who stay in touch with their families have improved chances on release.

But during the pandemic, like everywhere else, visitors have not been allowed. What makes it worse is that many of those on the inside are unable to read letters from home or write one back.

Ian Merrill, chief executive of the Shannon Trust, a charity that helps prisoners learn to read, says: “Fifty per cent of people in prison have a literacy level at or below that expected of a child leaving primary. Around 20 per cent of the total prison population read at a much lower level, where they’d struggle with the most basic tasks.”

Finding a job on leaving prison is not easy, but it doesn’t take much to realise how much more limited people’s options are if they can’t read. Learning to read is an effective, achievable and yet relatively unrecognised tool for reducing reoffending. It can reduce prisoner stress and vulnerability, improve resilience, self-confidence and future prospects.

Lockdowns have taken income away from hundreds of Big Issue sellers. Support The Big Issue and our vendors by signing up for a subscription.

Even before Covid-19, prisoners were often reluctant to admit being unable to read, often preferring to tick the same menu option and eat the same food every day rather than show vulnerability and ask someone to read the menu for them. Many have lived a life of bluffing to survive, and conventional education had clearly failed to reach them.

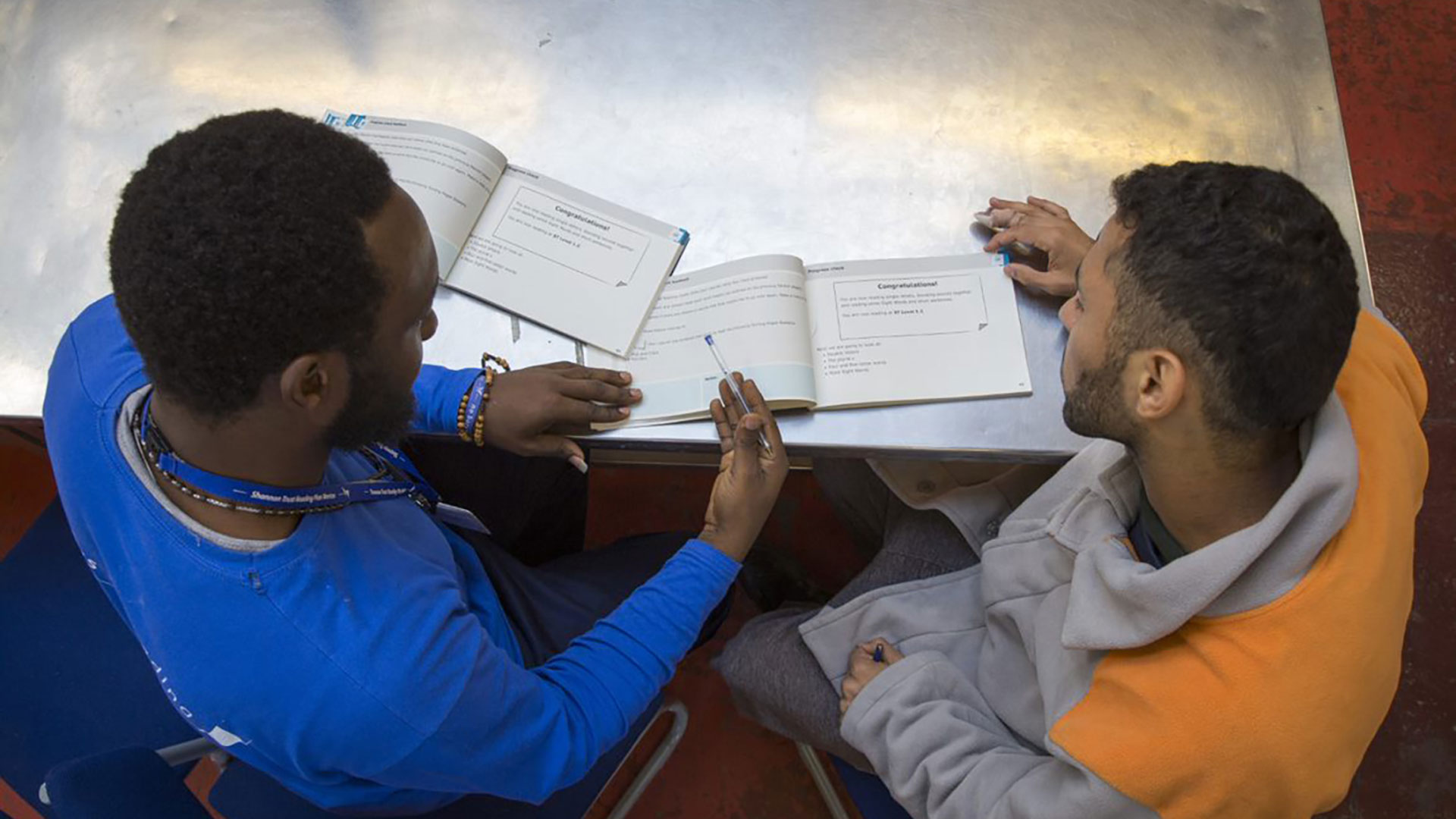

Shannon Trust’s confidential, one-to-one mentoring by fellow prisoners and reading guides have helped to remove the stigma felt by prisoners learning to read. A combination of achievable goals, small steps and a non-judgemental approach allows every learner to go at his or her own pace.