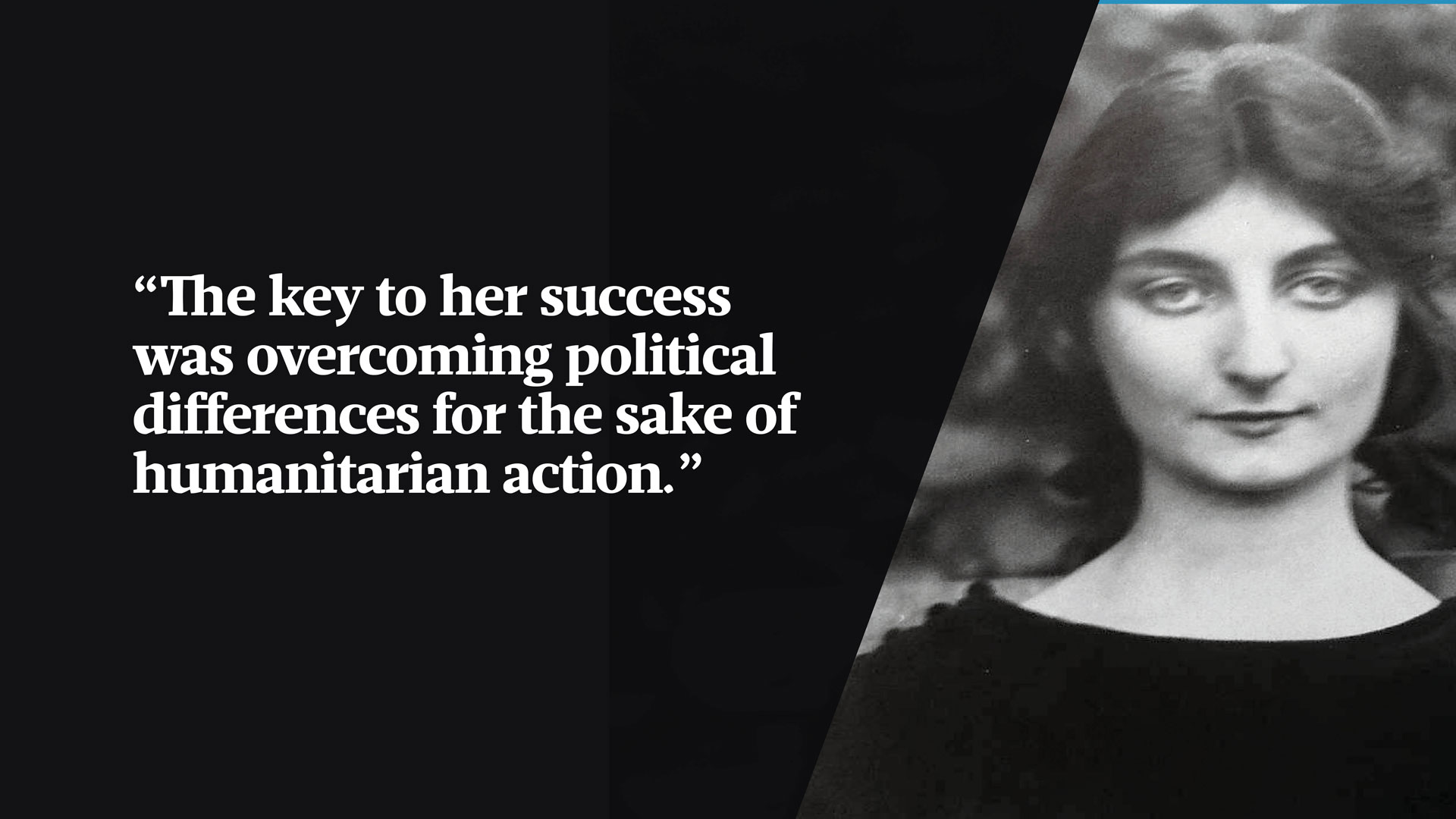

I first encountered Suzanne Spaak as a beautiful woman in a badly retouched photo. I was researching my last book, Red Orchestra, about an anti-Nazi resistance group in Berlin connected to a Soviet spy named Leopold Trepper. There she was, in Trepper’s memoirs, briefly mentioned in the text but gazing from the page.

She never met the Berlin group, which joined Trepper’s network after years of traditional resistance and rescue work. A Belgian national living in Occupied Paris, Suzanne’s ties to the Soviets were tenuous, yet she was often described as one of Trepper’s agents.

Finally in 2009, with the help of Google, I tracked down her daughter Pilette, an 80-year-old knitting instructor in suburban Maryland. “Everyone says Mama was a Soviet spy,” she sighed. “I wouldn’t care if she was, but she was actually something very different.”

I spent the next seven years piecing together the extraordinary story of Suzanne Spaak, the architect of an extensive network to rescue Jewish children in Paris from deportation to Auschwitz. Most were from poor Eastern European immigrant families. Spaak was not Jewish, Eastern European, or poor. Her coalition mobilised Protestants, Catholics, and Jews, as well as Socialists, Communists and Gaullists. The key to her success was overcoming political differences for the sake of humanitarian action.

Suzanne was the pampered oldest daughter of a Brussels financier but she was disenfranchised nonetheless. Her education consisted of needlework and household management; she studied literature and social policy on her own. It was illegal for a married woman to open a bank account without her husband’s permission, and women in France didn’t win the right to vote until after the war.

At 14 she fell in love with a neighbour boy, Claude Spaak, a member of Belgium’s leading political family. The young couple married at 20, but there was trouble from the start. Claude was chronically unfaithful. Suzanne compromised by settling on her best friend, Canadian Ruth Peters, as his mistress.