We spent our days instructing the public not to touch. Taking photographs was permissible. We worked in a museum of dolls. The dolls were all lifesize and made of wax, they were of short people and tall people, some of them were only of a part of a person – the head, for example, upon the end of a stick.

The public would come into see the dolls and rush from one to the other with great excitement. They recognised the dolls. They wanted to stand beside them. They wanted to touch, but we were there to discourage this. How the public loved “the doll shop” as we called it. We protected the dolls. Even when the public rushed about them pulling faces and making unkind comments, still they did not budge.

They were so stoical. So close to being alive, but never quite achieving life. They had such personalities, and in time working there we grew a great respect for them. Their stillness and silence began to feel dignified, and soon we kept silent and still beside them – alarming the public when, at last, we had to admit that we were not part of the doll fraternity, that we were poor flesh too. We could not keep still for very long. When the public leaned in close to our still bodies and commented upon how lifelike we looked, we said, very quietly, “Hello” and this made them scream. (We were not supposed to do this.)

Madame Tussaud modelled history, the best of it and the worst of it

The museum was Madame Tussauds, and in my early 20s I worked there making sure that the visiting flesh people did not harm the resident wax ones. This was their home after all, people should be more polite. But they weren’t especially. There is a certain melancholy to the wax figures. Stillborn and frozen, they hold the shapes of famous people as if they had no right to be their own person. They had no choice. How awful for the poor wax figure who may have wanted to have been – given the chance – Princess Diana, but instead was made Charles Manson.

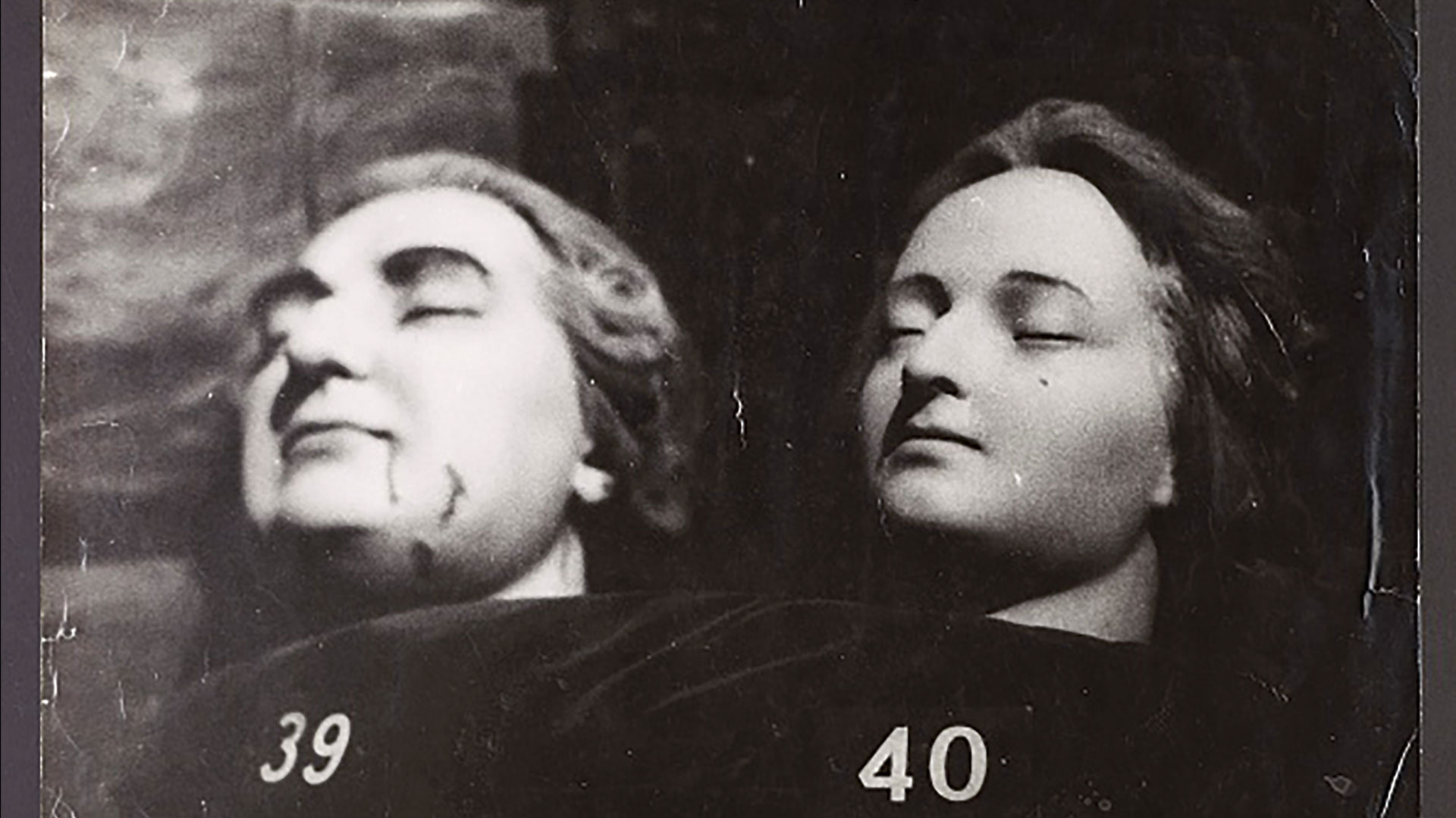

Among the waxworks were various figures modelled by the long dead proprietress herself, Marie ‘Madame’ Tussaud. She modelled Voltaire, Benjamin Franklin, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette (both their whole bodies and their guillotined heads), Napoleon and Jean-Paul Marat, captured in wax just after he was stabbed to death in his bathtub. She was in Paris through the French Revolution and was nearly killed by it – she was imprisoned (one of her cellmates was Napoleon’s future empress Josephine) and escaped the guillotine because of the fall of Robespierre, whose mangled head she cast.

Madame Tussaud modelled history, the best of it and the worst of it. She had an extraordinary talent for collecting the most celebrated physiognomies of her time. When Napoleon rose to power France only cared about Napoleon, and that was bad business for the waxworks. So she brought her wax people over the channel and showed the English precisely what the French Revolution was like. There was also a self-portrait. Tussaud showed herself as a small wizened woman with a large nose and chin and an intense smiling face. She seemed to be saying: ‘I am history!’