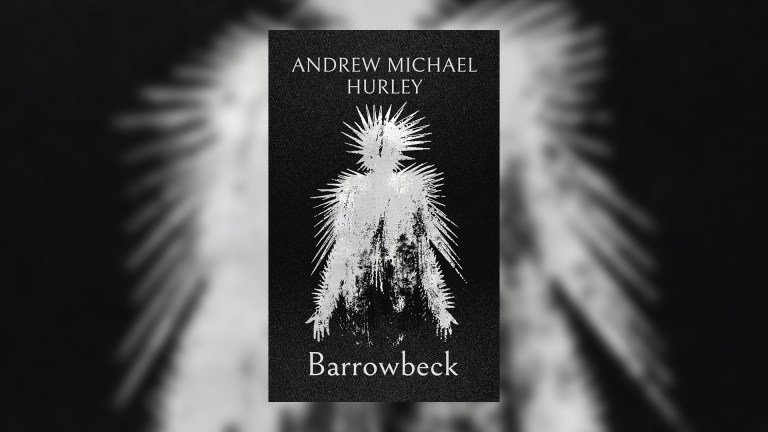

Like most abstract artists, David Lynch is wary of explaining his work in literal terms.

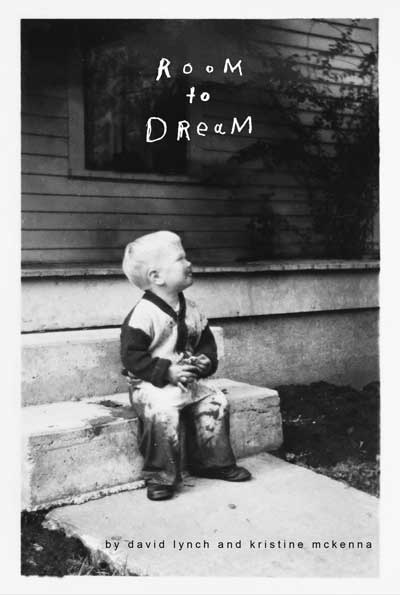

Nevertheless, he reveals quite a lot about himself and his creative process in this engrossing autobiography, Room to Dream. The clues are all there, you just have to join the dots.

Co-written with journalist Kristine McKenna, the book is a hybrid. McKenna provides biographical chapters featuring contributions from Lynch’s friends, family and colleagues, which Lynch augments with chapters inspired by what he’s just read. This approach almost certainly delivers a better sense of who he is than if he’d written the book alone.

Occasionally, he’ll gently contradict someone quoted in the previous chapter, but he mostly uses McKenna’s extensive research as a springboard into his memories. He doesn’t need much encouragement; this is a man who can clearly remember the “out of this world” taste of a cappuccino he drank 37 years ago.

We gain an abiding impression of a man who was born to live the uncompromising art life

Lynch writes like he speaks. He’s disarmingly direct, cheerfully profane and prone to bursts of giddy enthusiasm. Famously, he uses sweetly archaic expressions like “peachy keen”. However, at the age of 72, he now seems comfortable with exposing the steely single-mindedness behind that semi-affected public persona. He’s no naïf.

The chapters covering his Boy Scout childhood in 1950s Idaho are particularly revealing. The ‘Lynchian’ aesthetic was born there: a wholesome suburban environment plagued by creeping unease. Dead animals and dark roads feature heavily.