In the early days of the novel, English writers were known for their tales of the rural countryside. Bronte’s moors, Hardy’s chalk downs, the rolling fields of DH Lawrence’s Norfolk, and Austen’s great estates. Even today, American films use an establishing shot of a car struggling along country lanes to tell the viewer they’re in Limeyland.

But by the start of the new millennia, the novel in England became the home of the big city, with scarcely a pleasant pasture or cloudy hill in sight, and with that change, large parts of the country are now facing cultural invisibility.

It would be wrong to say publishing completely forgot the countryside. Helen Stanton, owner of Forum Books in Northumberland, suggests there has been a “brace of non-fiction” in the region from Pip Fallow’s Dragged Up Proppa to James Rebanks’ English Pastoral. In fiction meanwhile, readers can’t resist the allure of a handsome stableboy or a cosy hilltop murder, after all, the rural north “is a great location for crime fiction”.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

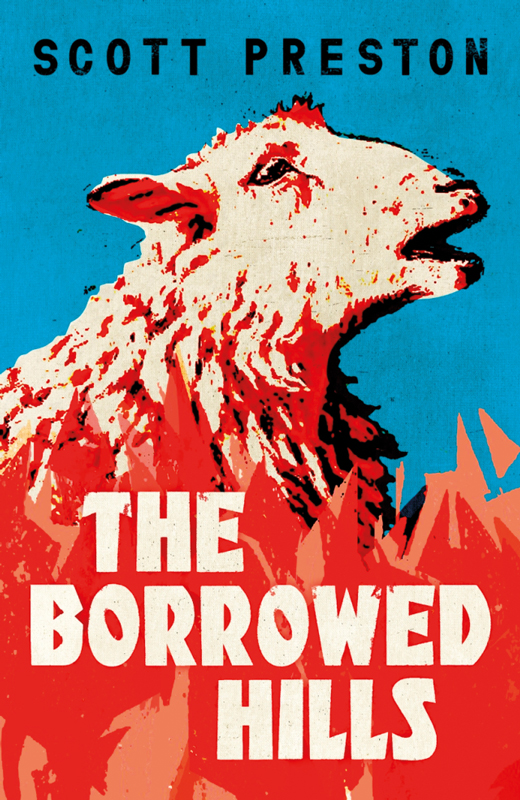

It’s in the literary novel, award-winning, state-of-the-nation books, where the disappearance of England’s countryside is felt most. Will Smith of Sam Reads, Grasmere, sums up the situation, “urban life rather than rural life dominate[s] contemporary fiction. Books set in small towns, villages or just showing rural life feel few and far between.” A handful of rural books stand out, such as Jon McGregor’s Reservoir 13 or Ben Myer’s Cuddy but when nearly 200,000 books are published yearly in the UK, the list is short. Shorter still when thinking about high-profile novels with meaningful things to say about country life.

The move away from the hinterlands wasn’t unexpected. The UK drifted from field to town during the industrial revolution and today is one of the world’s most urbanised countries with 84% of us living in cities, compared to around 30% in Austen’s day. Yet the division between urban and non-urban is messy, and what’s odd about publishing’s rural drought is how counterintuitive it is.