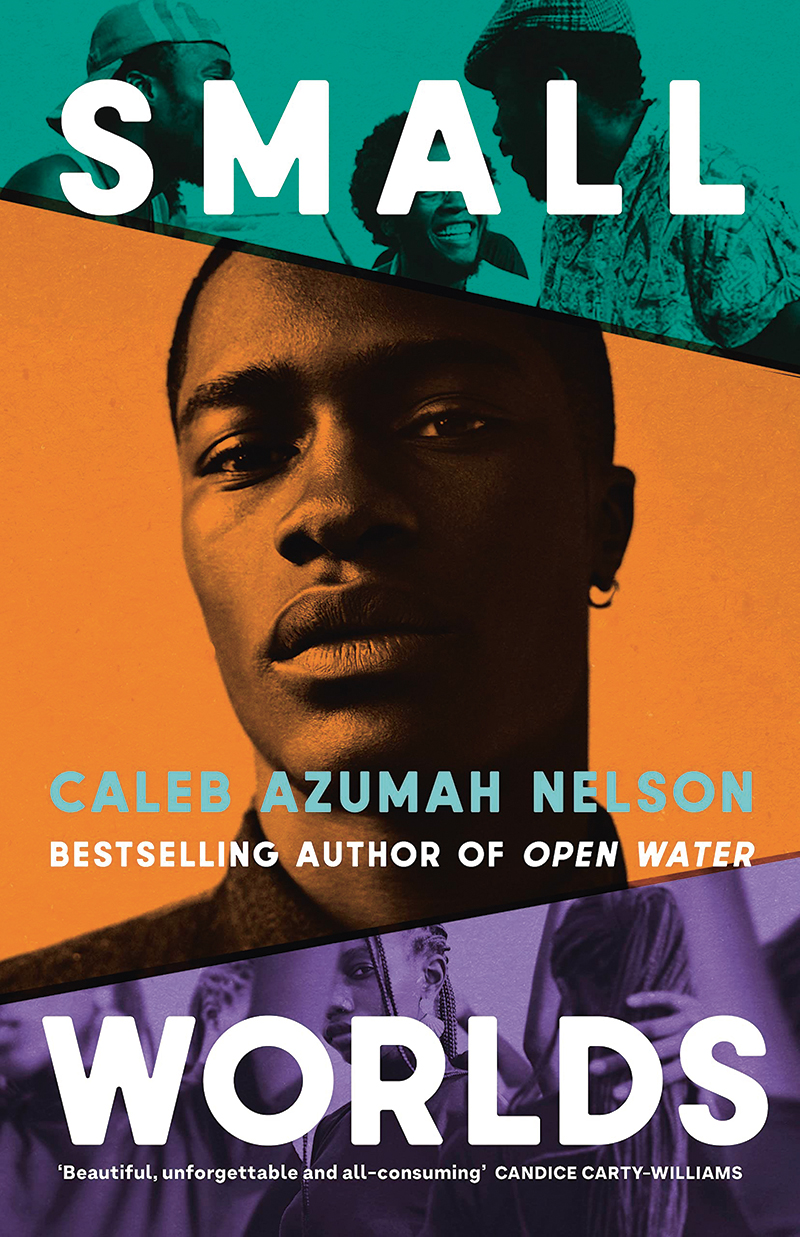

British-Ghanaian writer Caleb Azumah Nelson’s debut novel Open Water was a slam dunk. The South Londoner’s ode to music, aspiration and love met with instant hyperbolic praise, and his trophy cabinet (every young writer has one of course) heaved under the weight of numerous awards. Not one to hang about, just two years later the 29-year-old is publishing his much anticipated follow-up.

It’s a positive sign that Small Worlds shows no evidence of a ‘difficult second album’ panic to prove one’s breadth by moving from earnest soul to heady techno. It is a young love story and a study of Black experience, swaying back and forth from joyful feelings of freedom to fears of entrapment, propelled by the rhythms of gospel, jazz, garage and hip-hop.

Stephen has grown up “in song”; from “the shimmer of Black hands in praise” to the ecstatic chaos of “flailing limbs and half-shouted lyrics” in nightclub mosh-pits. His beloved best friend Adeline is a DJ who shares both his loss of religious faith and his love of dancing. A life basking in easy optimism in what seem like certainties for both of them inevitably progresses through disappointment, fear and potentially ruinous revelations.

Your support changes lives. Find out how you can help us help more people by signing up for a subscription

Covering three summers, moving back and forth from London to family trips to Ghana, from nerve-wracked gatherings around the TV to watch the World Cup to hot rowdy neighbourhood barbecues, Small Worlds is strongest when Nelson is describing, without too much holy awe, the accompanying sights, sounds and smells of these bonding events. But Stephen is no tough nut ready for the battering of bad news and unforeseen separations; his psychological skin is gossamer thin, and this can lead to occasional passages of overwrought prose suffused with the platitudinous language of self-help therapy. And there are times when one can’t help thinking, enough with the dancing metaphors, we get it.

Overall however, Nelson’s sincerity and brilliant knack for authentic characterisation creates a well of deeply felt sympathy for his lead actors, and an anxious investment in their futures. I did cry a number of times (not as often as Stephen) during moments of happy innocence and shocking grief, and I closed Small Worlds wishing I could hang around the neighbourhood a little longer.