His advice is not to dwell on whether events are good or bad, but to just inhabit the moment, embrace ‘the way of nature’ and ‘dwell in its unity’.

This sounds great and I’m sure we’d all love to just contemplate a bumblebee in the tranquillity of the forest, or dwell in nature’s unity, but this won’t get the dishwasher fixed.

I admire his attitude, and perhaps in China 2,500 years ago, the idea of ‘inhabiting the moment’ was radical, even revolutionary. Today, though, this sounds like exactly the kind of vague piffle that has spawned a multibillion-dollar happiness industry.

But Zhuangzi was clearly onto something in his unexpected advocacy, as this is a strand of happiness that seems to have endured over the centuries.

From around 1500, happiness became associated with the meaning we ascribe to it today, namely good luck, success and contentment. After all, ‘happiness’ comes from the Old Norse word ‘happ’, meaning ‘luck’ or ‘chance’.

This was the case until 1725, when Francis Hutcheson, an Irish reverend and philosopher, wrote a treatise catchily titled An Inquiry into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue.

Hutcheson posited the idea that happiness should be less about gratification and pleasure, and more about civic responsibility. So basically, stop eating crisps and pushing your mate into a hedge for a laugh, and help out a bit.

This was a less indulgent version of happiness, which influenced the writers of the 18th century, including those who drew up the Declaration of Independence.

The famous phrase ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ was not an invitation to crack open the sherry and play pin the tail on the donkey until the police are called, but rather the more sober pursuit of duty and contentment, finding a meaningful role and a sense of purpose.

Since then, I imagine, the decline in the usage of that phrase has mirrored the fact that happiness has come to mean hedonism, pleasure, fun, enjoyment.

The word happiness reached peak usage in 1803, and was thereafter in steady decline, reaching an all-time low in 1988.

I don’t know why 1803 particularly prompted the word ‘happiness’ to be bandied about so much, although perhaps the reason here in Britain was that we were at war with France.

It might have been due to the opening of the Surrey Iron Railway, the first public railway between Wandsworth and Croydon, meaning that Croydon was now opened up to bring families together. ‘Oh, Aunt Agatha lives in Croydon, and now we shall see her most every week, oh, happiness unbound!’ said the advertisement, I imagine.

And perhaps 1988 was a turning point for happiness. As this shiny hollow decade of unbridled materialism, big hair and partying neared its end, there were strikes and unrest.

The world was maybe poised to turn a corner and rediscover a more meaningful kind of happy. It seems that way, as since the late Eighties the word happiness is enjoying a resurgence and is again on an upward curve.

Our lives are full of wishing, luck and superstition. Rituals, numbers, traditions are found in every culture on the planet. I am not a betting man, but once I couldn’t help but abide by Zhuangzi’s doctrine and go with the flow. I was on the phone and during the conversation, I said the phrase ‘blessing in disguise’.

As I said the words, the exact same phrase was spoken on television by the commentator, referring to a horse: ‘. . . and in the 3.45, at 14 to 1, Blessing in Disguise.’

It was as if I had lip-synced it. A sign surely! Time to inhabit the moment. It was 3.35 in the afternoon, so I cut the phone call short, and immediately went to the betting shop in my street.

All I had on me was a fiver, which I’d found under a piece of Dundee cake. ‘Five pounds on Blessing in Disguise, please.’ ‘To win?’ ‘Of course, to win!’

I stood and watched the race, my face beaming with the delight of an utter novice, my once-in-a-blue-moon flutter. I knew the horse would win, I had just been given a clear message from the ‘Dao’ of horse racing, the god of good fortune. I was subjecting to ‘the way of nature’.

I had been shown the future – just a glimpse of it.

And sure enough, Blessing in Disguise romped home the winner by two lengths.

I took my £75 and I could lie and say I started a foundation for lonely pheasants, but I didn’t. I bought some new hiking socks and with the remainder I took my wife out for dinner, and we toasted our blessing.

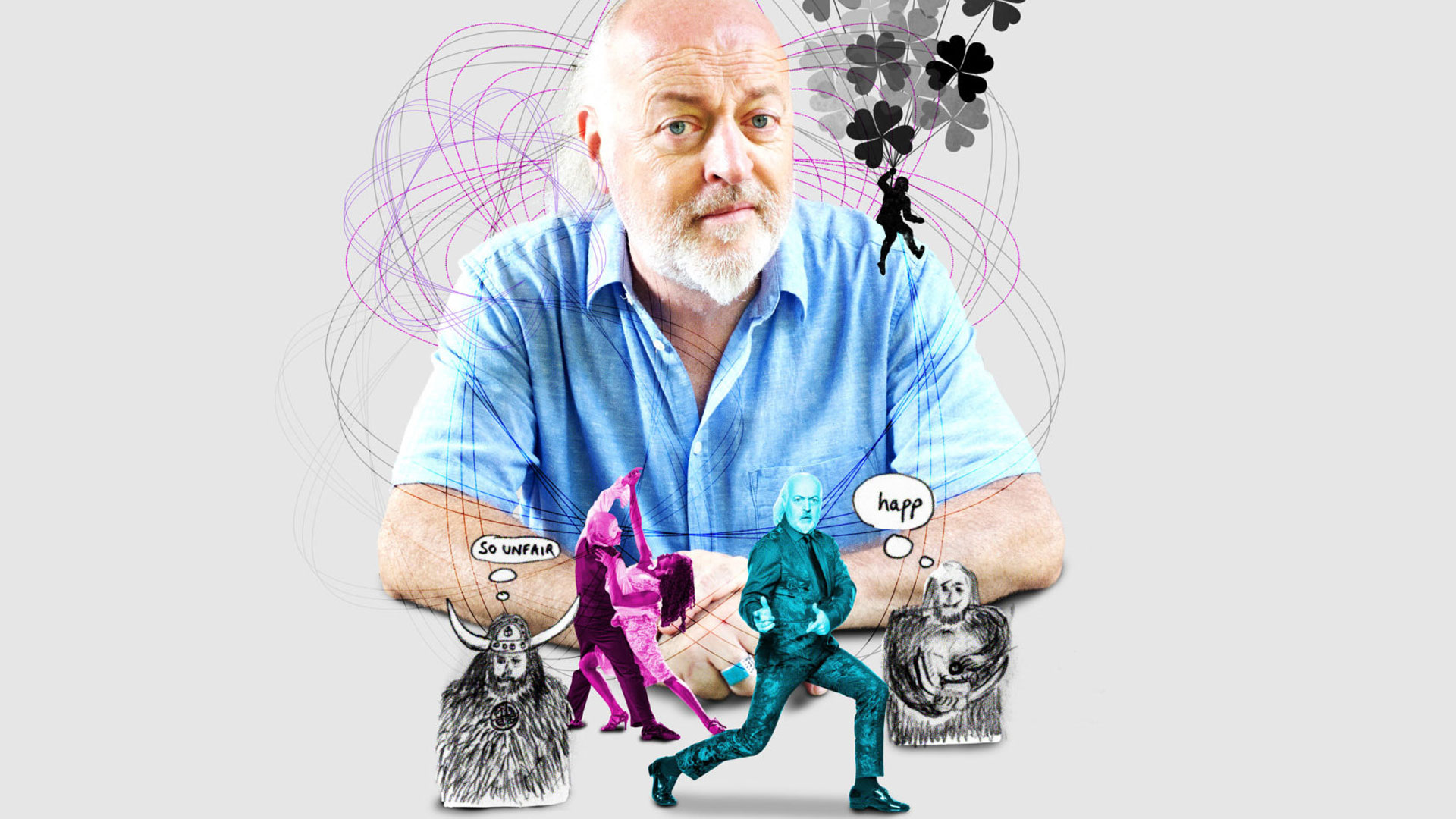

This is an extract from Bill Bailey’s Remarkable Guide to Happiness, out now (Quercus, £20)