Ten years ago I planned to write a book.

President Barack Obama has just been voted into the White House and the funny thing about the 44th leader of the United States was that he was a bit like me, if slightly more powerful. And successful. And funnier. And better looking.

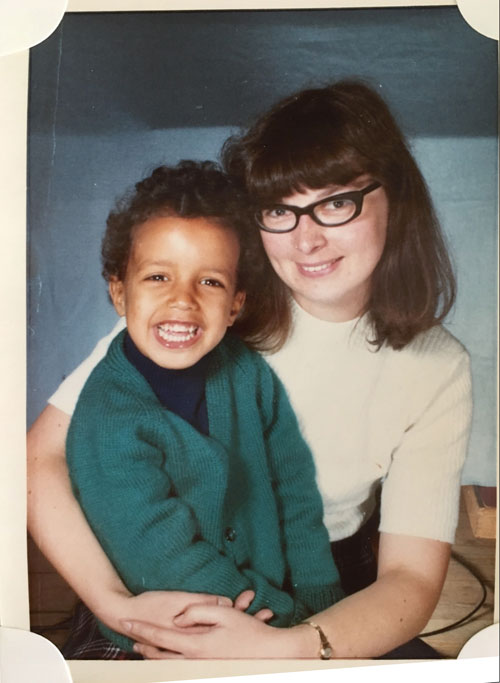

Our similarity came from our heritage. President Obama had a father from Kenya who was black and a mother from America who was white. I had a mother from Yorkshire who was white and a father from Sudan who was black. Which made me mixed-race, just like the newly anointed most influential man in the world.

It wasn’t called mixed-race in those days. Half-caste was more common. Jungle bunny sometimes. Or Paki.

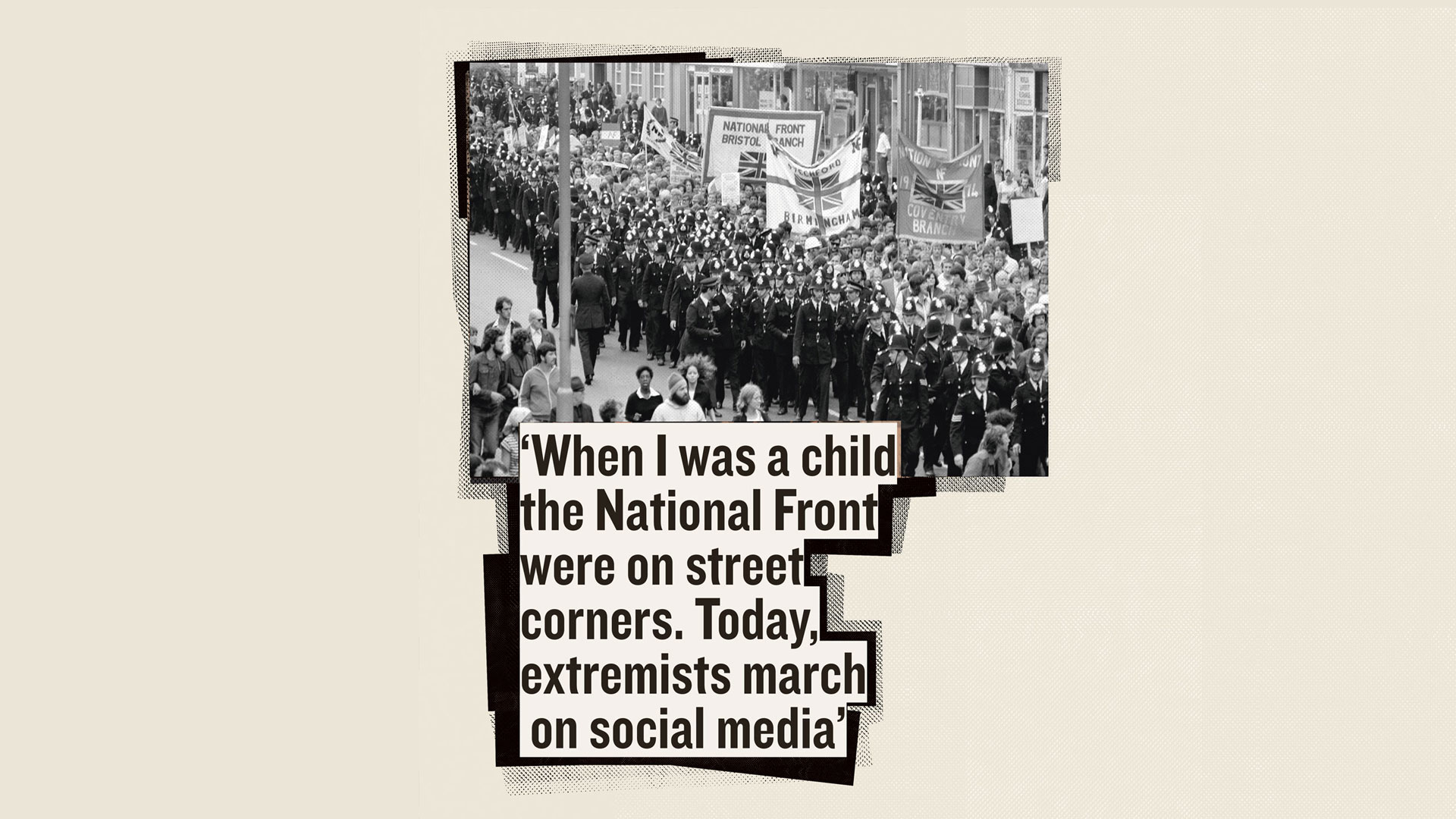

When my mother and father met it was very unusual for a white woman and black man to marry. This was still an era – the 1960s – when “coloureds” was a part of everyday language, the Black and White Minstrels were on television and there were signs in windows in boarding houses saying all were welcome apart from black people, Irish people and dogs. Local by-election posters in the West Midlands said “If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour”.

And given it was unusual for a black man and white woman to tell the world they loved each other and get married, that made me unusual. I was the only mixed-race child in my class at school that I knew of, with a shock of curly hair and brown, Adidas Gazelle, trainers. It wasn’t called mixed-race in those days. Half-caste was more common. Jungle bunny sometimes. Or Paki.

So, when a mixed-race guy was suddenly on the front page of pretty much every newspaper in the world, I thought it was a moment to write about being mixed-race in Britain. So I started collecting little snippets from the papers, speaking to my family and thinking about the kind of country we were.