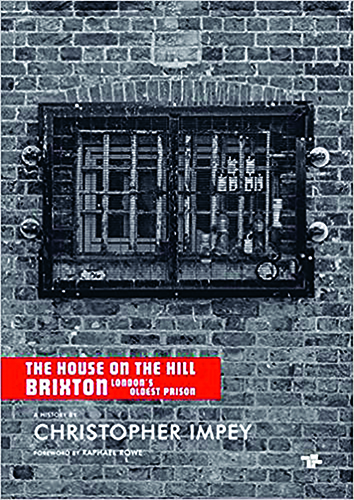

Brixton is London’s oldest prison and this year marks its bi-centenary. Over its 200 years, it has held hundreds of thousands of people and while all of them have different stories to tell, most are connected by poverty, disadvantage and the feeling of being cast out. Throughout its existence, the jail has long been at the heart of the prison debate, as pioneering as it has been ruthless.

Those sent to Brixton immediately after it was built in 1819 were truly destitute. London had swelled to become the first city in the Western world to reach the million mark and many of its inhabitants were migrants from the countryside, looking for a better life in the city. Instead, they found themselves living in the dirt and squalor of slums and doing whatever they could to make ends meet.

It meant Brixton had no shortage of guests. Most had been convicted under the Vagrancy Act – legislation passed in the 1820s which made it an offence to sleep rough or beg and which remains in place today. They were punished beyond their loss of liberty by being made to climb the treadmill. It looked like a giant, elongated waterwheel; its victims – men, women and children – had to tread the boards that ran along it for up to eight hours a day.

Among them was Edward Dando, the oyster eater. My discovery of his story inspired me to write my book, The House on the Hill. His modus operandi was simple – he feasted on what he couldn’t afford, touring London’s eateries consuming huge quantities of food then refusing to pay. Oysters were his weakness which, at the time, were a staple of the London poor. He served a string of sentences punctuated by what he liked to call ‘blow-outs’ at oyster shops. He died in poverty, though Charles Dickens wrote fondly of him, imagining ‘he was buried in the prison yard and they paved his grave with oyster shells.

Those sent there were guilty of the most serious crimes.

London continued to grow, and by the middle of the century Brixton became so overcrowded it had to be shut down. In 1853, it reopened as a prison for convict women – the first such jail in the country. Those sent there were guilty of the most serious crimes. Until then, they would have expected to have been transported to Australia, a policy which had suddenly been brought to an end when the Australians, understandably, began to object.

Brixton’s uniqueness as a women’s prison was reflected by its complement of around 70 staff which was almost entirely female; Victorian sensibilities precluded men from being in charge of women. This included the de facto governor, the remarkable Emma Martin, who lived in the prison with her 12 children.