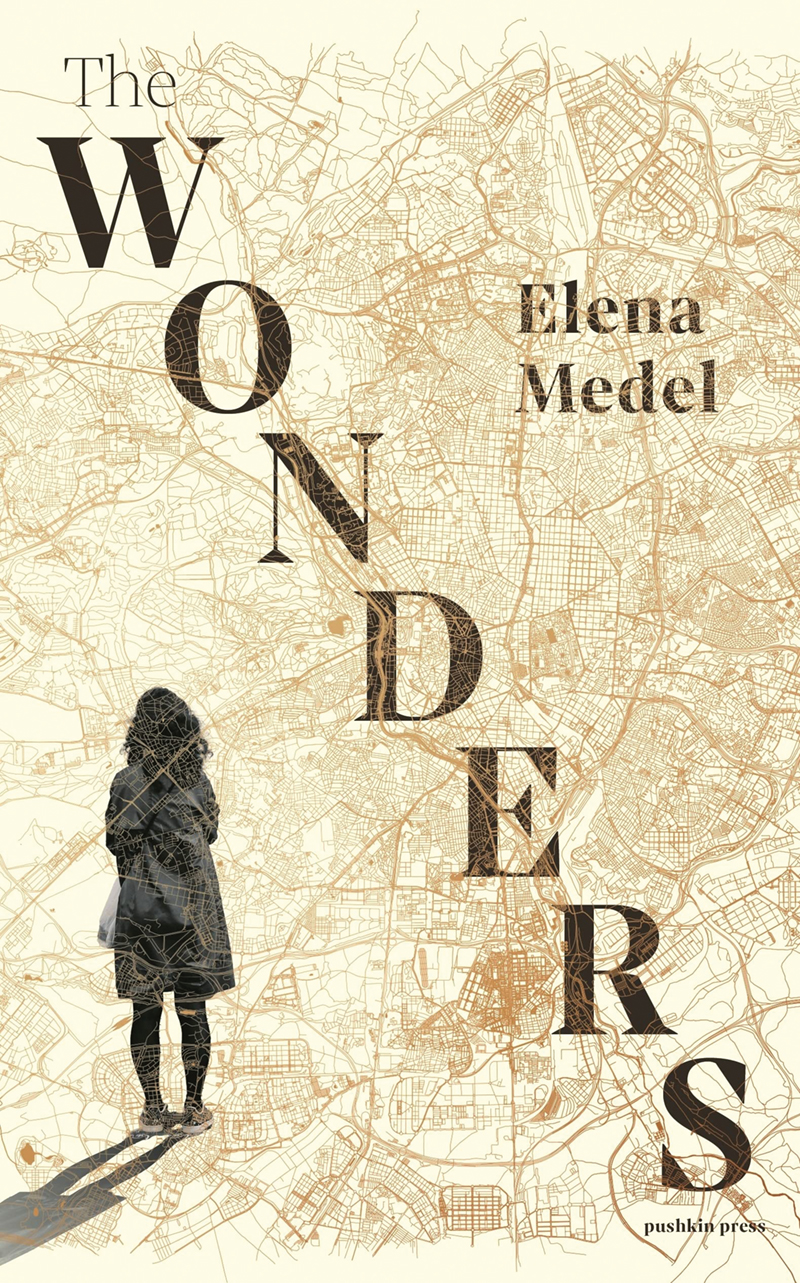

There are plenty of novels out there telling us that money isn’t really important, that we should live a life of the soul free from pecuniary complaints. So it’s something of a guilty relief when a novel comes out reminding us of the banalities of our reliance on cash, the necessity of it to our existence, and, more importantly, the importance of not ending up with none of it.

The characters in Elena Medel’s The Wonders spend most of their time on the brink of having none of it. It tells the story of Spanish working-class women – impoverished either by tragedy or by family breakdown – and the simplicity of their struggle for two things: money and power. Though it is perhaps more about their struggles without those two things, about the luxuries they never have and the easy lives they never lead.

This makes it sound a misanthropic read – it is not. Maria and Alicia may not love their lives as cleaners and carers – described through different decades in Madrid – but they are endearing characters under Medel’s pen. Maria battles to stay afloat in the monotony of her life as a cleaner, obstinately waking every morning to clear Madrid’s office blocks in order to get just enough to buy her partner an extra beer at the the end of the week. But on Saturdays, she joins the women of her neighbourhood, away for a moment from their work or their men.

Ultimately, this is a novel about consistency and change, how situations and conditions may not change, but attitudes will. In the early ‘80s, Maria discusses feminism with her neighbours as they tentatively question their drink-sodden husbands, who squander their week’s money on beer and cigarettes every Friday. The novel ends more than three decades later, with the biggest women’s rights march in Spanish history.

Alicia is Maria’s granddaughter, but they have never met; Maria is estranged from her own daughter, and has never seen a picture of her grandchildren. Describing the details of their pasts is where Medel’s narrative slightly slips up. Alicia grows up in apparent prosperity, bullying her poorer schoolmates about their sloppy clothes and tiny Tvs. Yet Alicia’s father has been cheating himself about his wealth, and kills himself when Alicia is still a teenager.

Medel’s depiction of the effects of this trauma seem disjointed – at once tragic, then almost comic, or flippant. The reader is certainly disturbed, but the pain of this episode seems to be manufactured, forced, thrown in at horrifying moments and then abandoned and seemingly irrelevant. It is a novel of vignettes, episodes from different decades and different lives, which are obviously intertwined. But the reader is also left perplexed as to how it is to fit together; there is no reconciliation, no resolution. Only the hope and expectation of better things that must surely be around the next corner. Somehow, though, that is enough, in this powerfully strange, translucent, but empathetic novel.