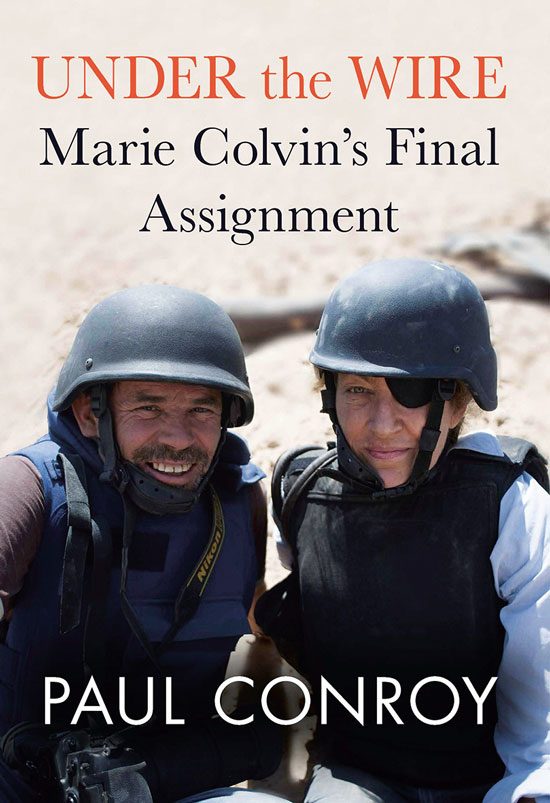

Under The Wire was my attempt at telling the story of my own and legendary correspondent Marie Colvin’s final assignment to Syria. Marie’s death in Baba Amr, at the hands of the Syrian regime, caused international outrage, but it’s never easy when the journalist becomes the story; the book was my attempt to refocus the glare of publicity sparked by her death back onto the Syrian people.

When we entered Baba Amr in February 2012, the situation in Syria had escalated to terrifying proportions, but the world was paying scant attention to the besieged neighbourhood of Homs. Marie and I had spent the vast part of 2011 covering the Libyan uprising, where we spent two months covering the siege of Misrata. We endured a sustained rocket and artillery barrage from Gaddafi’s forces and thought we had seen the worst humanity had to offer. After one evening of the withering artillery bombardment unleashed by Assad’s forces, we were forced to think differently. Bashar al-Assad had surrounded the district in a ring of steel and units of the elite 4th Division, commanded by his brother, Maher, and they were intent on reducing the area, and its 28,000 civilian population, to rubble. Marie was determined to bring this story to the world.

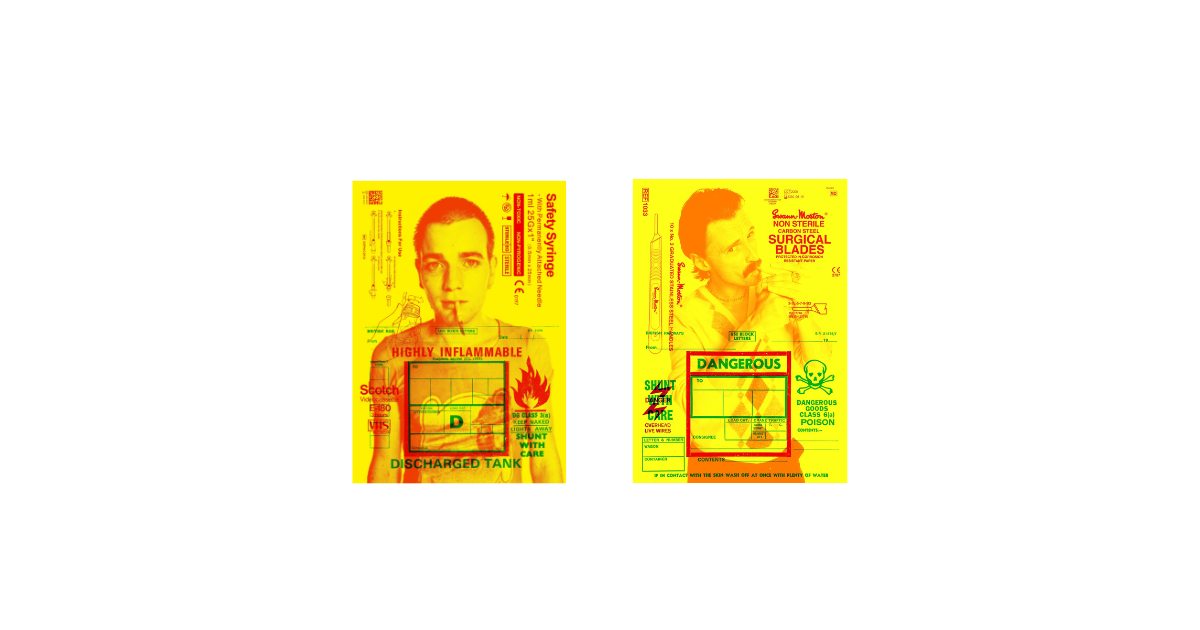

Marie had little time for the weapons and logistics of war

Marie’s gift as a correspondent and writer was her unique approach to covering conflict and war. She had little time for the weapons and logistics of war; she couldn’t identify a MIG jet from a Lancaster bomber. Her focus was on the plight of the victims, those who feel the full force of the military machine in its many guises, the women and the children. When Marie witnessed war, it was through the eyes of terrified children and traumatised parents hiding in dark basements, as explosive hell was unleashed all around them. In a world of high-definition videos of smart bombs, neatly picking off their targets, the world often forgets the plight of the weakest, and often unseen victims of war. Marie never did. This is what drove us to one of the most dangerous places on the planet.

Working with Marie was the most fulfilling and productive spell of my career as a photographer. We both shared a vision of how we wanted to portray war, and the devastating effect it has on the people where the ‘dumb’ bombs and bullets fall. In all of the time we worked together I can’t ever remember her saying, “Hey, take that shot”, and I can’t recall, when reading her finished piece, thinking, “Damn, she missed something.” It simply didn’t happen.

When working in such environments, you need to be extremely focused and the ability to be able to relax with your partner can’t be overstated. On occasions too many to remember, I can remember driving down a desert road, or through an abandoned town and, all of a sudden, we would look at each other, nod and without a word being spoken, we would turn around and find another route. That’s just how it went. You can’t define that process, and you certainly can’t recreate it.

In Under The Wire I hope I have explained what we do, and why we do it and I have addressed the accusation that war correspondents and photographers are simply ‘war junkies’. It’s a phrase I hear often and it makes me wince. I can assure anybody willing to listen that there are far easier ways to get an adrenaline hit than being shot at.