Music has always been immensely important to me, as crucial a part of my emotional development as books and family. As a music journalist, then a radio producer, I learned much about the world – the religious rituals of medieval monks to the history of civil rights – from a record collection which went from Gregorian chant to Japanese noise. But what most fascinated and vexed me, both as a reader and a critic, was getting to the nub of how music makes you feel. How can a bunch of notes and chords, delivered by simple machines and human voices, leave our bodies vibrating with ecstasy or wretched with grief? It is a miracle. And how do you write about that?

Coleman writes about his favourite singers as Gabriel García Márquez might a cherished lover

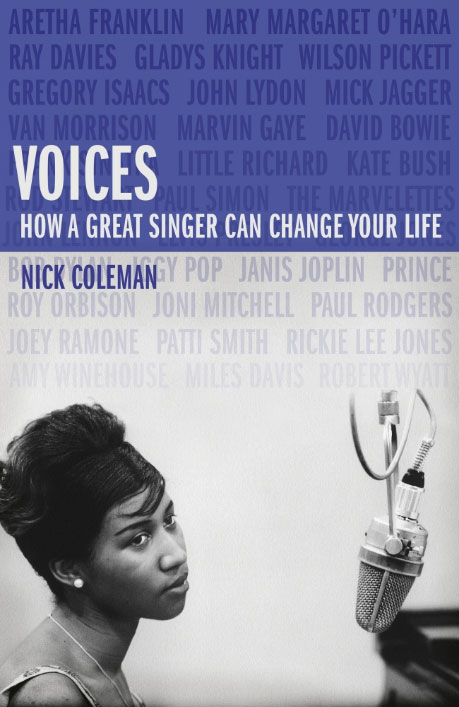

Longform music journalism thus tends to focus on social history or academic study. It is often very dull, though some brilliant work has certainly been done, often by writers with a strong poetic bent, like Lester Bangs, Paul Williams and Patti Smith. Their primarily emotional response is not common among British writers, who prefer to ensure credence by the authoritative dissemination of facts. This is what makes ex-NME scribe Nick Coleman’s Voices: How a Great Singer Can Change Your Life so unusual and affecting. Coleman writes about his favourite singers as Gabriel García Márquez might a cherished lover. He trembles, he gasps, he laughs out loud, and sometimes he has a little cry. He just gets it.

He understands that music is a slippery bugger to tackle with words

That’s not to suggest that Coleman isn’t an elegant, controlled writer whose curiosity is as engaging as his whooping passion. He writes exquisitely about every aspect of the singing voices of the likes of Wilson Pickett, Frank Sinatra and Joey Ramone (“a fat baby seal.. abandoned by its mother”), often moving from a scholarly dissection of timbre, stylistic flourishes, phrasing and range to his personal response to a cracked Van Morrison note or an unexpected ‘wistful’ inflection among Aretha’s effortless flow. He understands that music is a slippery bugger to tackle with words, so subjective is our experience of it (this is very much a book by a white English man born in the early Sixties). But by combining his passion, his knowledge and a thoughtful contemplation of his own place in an often hostile world, he has, to use the modern parlance so beloved of that great music man Simon Cowell, nailed it.

If you want a flavour of what he does so well, have a read of his piece on one of Bob Dylan’s great masterpieces, Blind Willie McTell. His description of Dylan, “fists at the piano”, pounding out his “rapturous” meditation on slavery, “channelling the singing language as if hooked up to some other current” is thrilling. Partly because I can confirm he’s right about everything that makes this song so compelling. But mostly because it’s clear Coleman just fucking loves the song. Bravo.

Peach, the debut novel of young Welsh writer (and paediatric nurse) Emma Glass, is an impressive achievement. There are obvious Joycean and Eimear McBridean influences on her writing, which is rich with onomatopoeia, musical rhythm and graphic, bloody imagery.