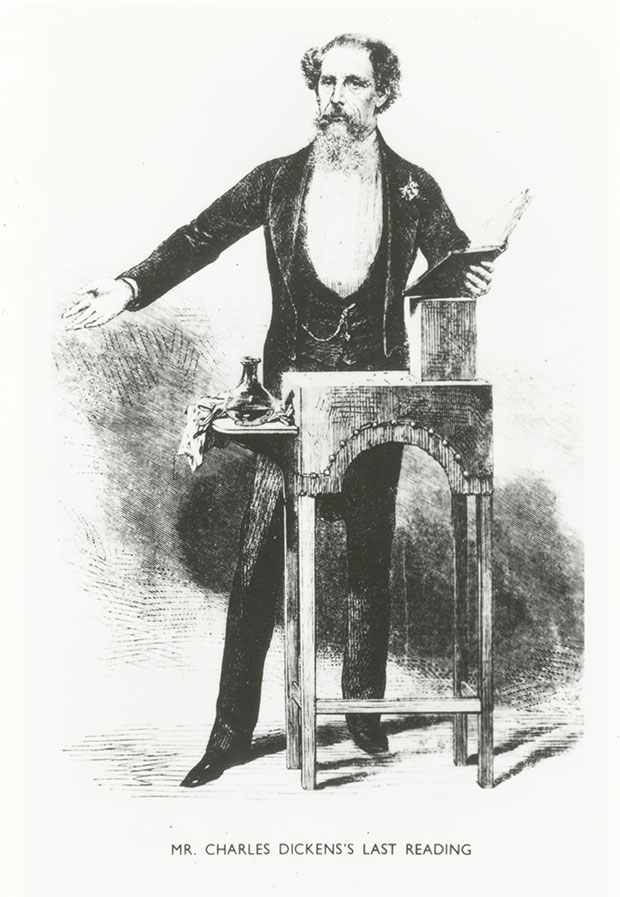

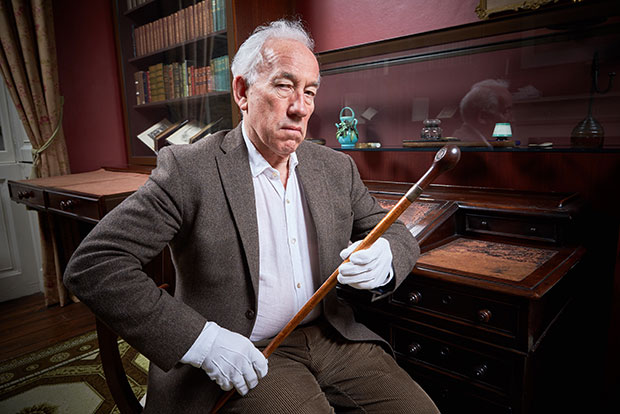

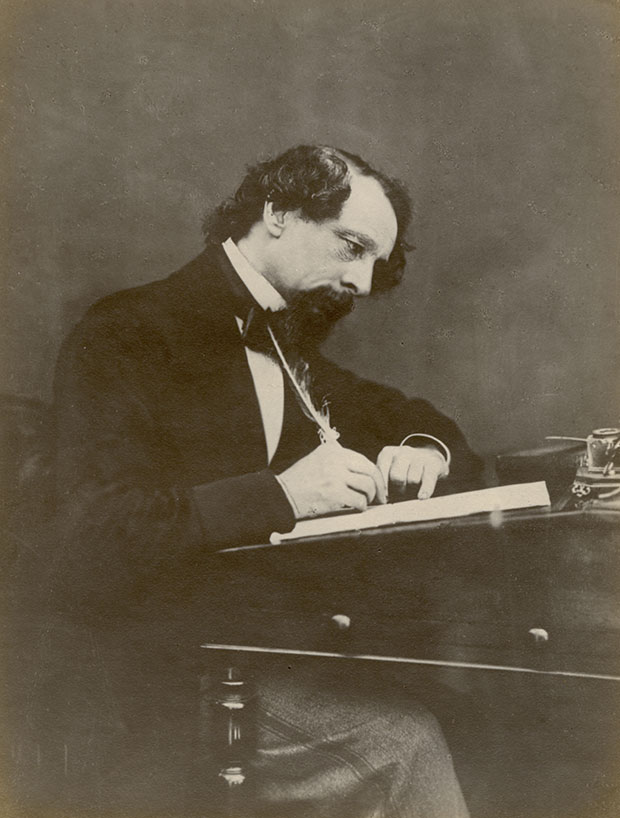

It is three feet tall, likely made of oak, and can be viewed between the hours of 10 and five at 48 Doughty Street in the Holborn area of London. The walking stick of Charles Dickens (below) is too valuable a relic to leave the museum that now occupies his former home, but at one time it would have gone everywhere with him – as marks of wear on the grip and tip attest. While the hand that held it and the feet it helped along are now bone and dust beneath the flagstones of Poet’s Corner, the brain of the author, and, indeed, his heart are still evident to anyone who cares to read his work. More, Dickens’ walking stick stands as a better symbol of the man than his writing desk and chair – both of which the museum also owns. It is a reminder that he saw the world on foot, that the rhythm of his steps was the rhythm of his mind as he flitted, a restless shadow, through the city.

“Dickens liked to walk 12, 15 or even 20 miles a day,” says biographer Claire Tomalin, “and he got very lost if he couldn’t walk like that. I think he used walking to nourish his imagination.” Also, one suspects, to nurse his wrath. Dickens was a habitual, even obsessive visitor of workhouses, prisons, fetid midnight streets, and any area of London – and elsewhere – where the poor lived and suffered and too soon died. His great subject as a writer and social activist, those he sought to portray and protect, were, he said, “the rejected ones whom the world has too long forgotten, and too often misused”.

His championing of these people is world famous, of course, in great novels such as Oliver Twist and Little Dorrit, but much less well known now is that Dickens was a journalist and magazine editor dedicated to exposing social evils, and a campaigner dedicated to eradicating them. It is this rather forgotten aspect of his life and work that the Charles Dickens Museum – in association with The Big Issue – is seeking to highlight in the forthcoming exhibition Restless Shadow.

Were Dickens to walk from his grave in Westminster Abbey today, he find plenty to anger and energise him in our society

Dickens worked as a reporter from 1829, when he was 17, and from the early 1830s covered the House of Commons. Joining the staff of the Morning Chronicle, he began publishing sketches of London life which would first bring him to public attention. Success as a fiction writer arrived in 1836 with The Pickwick Papers, but he had by no means forsaken journalism. In 1850, he established a current affairs magazine, Household Words, writing and commissioning others including Elizabeth Gaskell and Wilkie Collins. Household Words has been an inspiration for the direction of The Big Issue under the editorship of Paul McNamee. “It’s the idea of highbrow populism, which is a driving force of what we do. That’s from Dickens.” Dickens established a second magazine, All The Year Round, in 1859, and this was where his classic essay Night Walks, republished here, first appeared. The walk through London he describes so atmospherically (which Google Maps suggests was about 10 miles) was prompted by a bout of insomnia caused by “a distressing impression”. This is thought to have been witnessing his father undergoing surgery without anaesthetic; his room, as Dickens wrote in a letter, was “a slaughter house of blood”.

There were an estimated 70,000 rough sleepers in the capital, and Dickens encounters some on his walk. A young man rises before him, a ragged spectre, feral with cold, from the steps of St-Martin-in-the-Fields, and one thinks of George Orwell’s essay, Hop Picking, in which, intending to shelter in the crypt, he spends the night instead on benches in Trafalgar Square. One thinks too of The Big Issue, launched in 1991 at St Martin’s.

Were Dickens to walk from his grave in Westminster Abbey today, he would no doubt find plenty to anger and energise him in our society. We may have a welfare state, which his Britain did not, but it is striking how the inequities of his time chime with the inequalities of our own. I am writing this in Glasgow where, in March, Matthew Bloomer, 28, just a little older than the man Dickens encountered, froze to death on a pavement outside a department store on one of the city’s main shopping streets. “Why, in the name of a gracious God, should such things be?” Dickens asked, during a visit to Scotland, on witnessing a dying child. It is a question that anyone might, on hearing Matthew Bloomer’s story, very well repeat.