David Lynch is sitting on a paint-splattered chair, backlit by bright Californian sunlight that floods through a large window. Cigarette smoke envelops him, like a cloudy thought bubble, but his expression still pokes through the haze. Is this David Lynch at work, lost in the faraway business of artistic inspiration? Or is he simply taking a moment, enjoying a fag break while a documentary crew impertinently pokes around his Los Angeles studio?

This is an image that filmmakers Jon Nguyen, Rick Barnes and Olivia Neergaard-Holm keep returning to in their portrait of the American director. The view of Lynch in his studio that joins his house is intimate, so intimate that the 71-year-old’s toddler daughter frequently wanders into the space to join him. But you’re still left wondering: what’s on his mind? As if you’d want it any other way, Lynch retains that sense of enigma, of velvety mystery that runs through his best work.

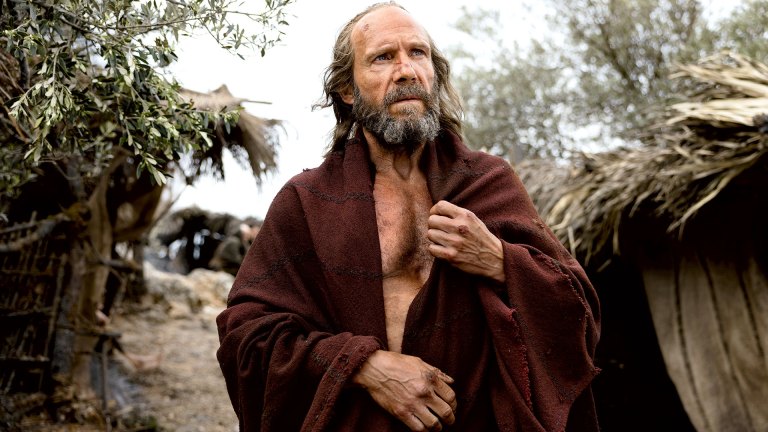

Not that David Lynch: The Art Life is without moments of revelation or insight. As its title suggests, the focus here is on Lynch the painter (This Man was Shot 0.9502 Seconds Ago, above) and sculptor rather than Lynch the filmmaker. While there’s always been blurring and overlap between these two practices – Lynch describes cinema, at one point, as “a moving painting, only with sound” – the documentary is likely to disappoint those wanting a potted account of his best-known movies.

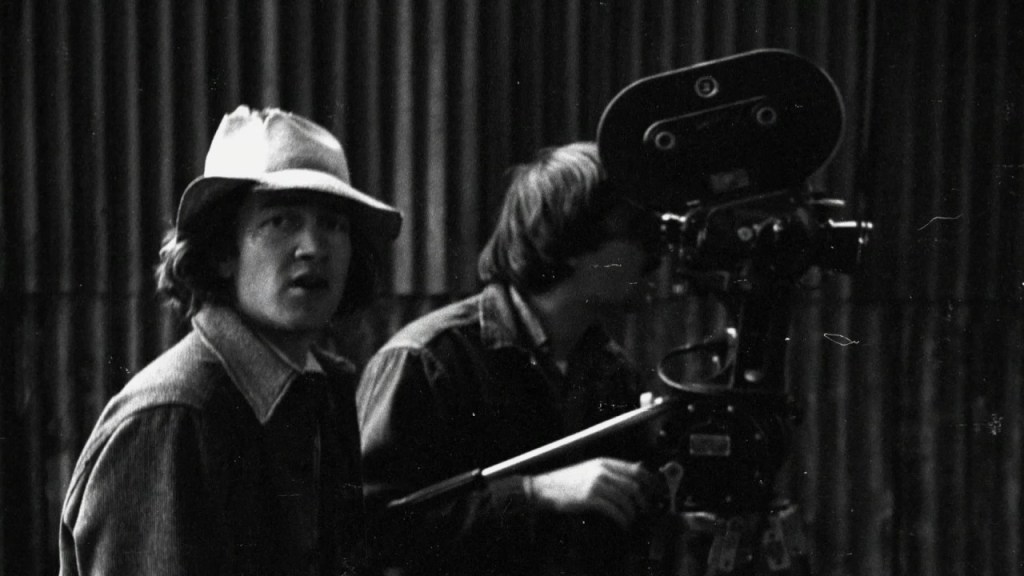

Blending archive (notably home movies of Lynch’s mostly happy childhood), sequences of the artist at work in front of a canvas, and a generous if not always illuminating voiceover from Lynch himself, the film takes us up only to the making of his debut feature Eraserhead. Released in 1977 but produced over a four-year period while he was at film school in Los Angeles, the film effectively marks the beginning of Lynch’s movie career. And as the documentary concludes, the dark, unsettling triumphs of the decades to come – The Elephant Man, Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart, Mulholland Drive, Twin Peaks and more – are just ahead of him.

Still, it’s impossible not find echoes of these cinematic masterpieces in this film’s absorbing look back at Lynch’s upbringing, his years at art school, and his struggles as an artist. Sometimes you can’t help thinking about specific films. His description of his years as a kid, brought to life through soft-focus Super 8 and family photographs, is pure Blue Velvet, for instance: outwardly suburban bliss, but underpinned by vague menace.