Growing up in Tasmania, Saroo Brierley had a map of India on his wall. “The map’s hundreds of place names swam before me in my childhood,” he recalls. “Long before I could read them, I knew that the immense V of India was teeming with cities and towns, with deserts and mountains, rivers and forests – the Ganges, the Himalayas, tigers, gods! – and it came to fascinate me. I would stare up at the map, lost in the thought that somewhere among all those names was the place I had come from.”

Until the age of five, Saroo lived with his mother, two brothers and baby sister in a remote, impoverished town called Khandwa. Accompanying his brother to work in a nearby town one day, he got lost and trapped on a cross-country train. He ended up almost 1,500km away, across the country in Calcutta (now Kolkata), alone, unable to find his way back, with others seeming more likely to abuse rather than help him. After spending several weeks on the streets, he was sent to a government juvenile detention centre, and later an adoption organisation. They tried to trace his family but Saroo could not remember enough details about where he was from for his family to be traced, and so it was arranged for him to be adopted by a couple in Australia.

Since I was a kid, I’d go to bed and have these dreams The Brierleys offered Saroo a loving home, but he was haunted by the memories of the life and family he had lost. “It was traumatic to have these memories and this feeling of uncertainty but I learned how to deal with it,” Saroo says from Tasmania, where he still lives. “Since I was a kid, I’d go to bed and have these dreams… But what was a burden for such a long time really kept these thoughts and memories alive.”

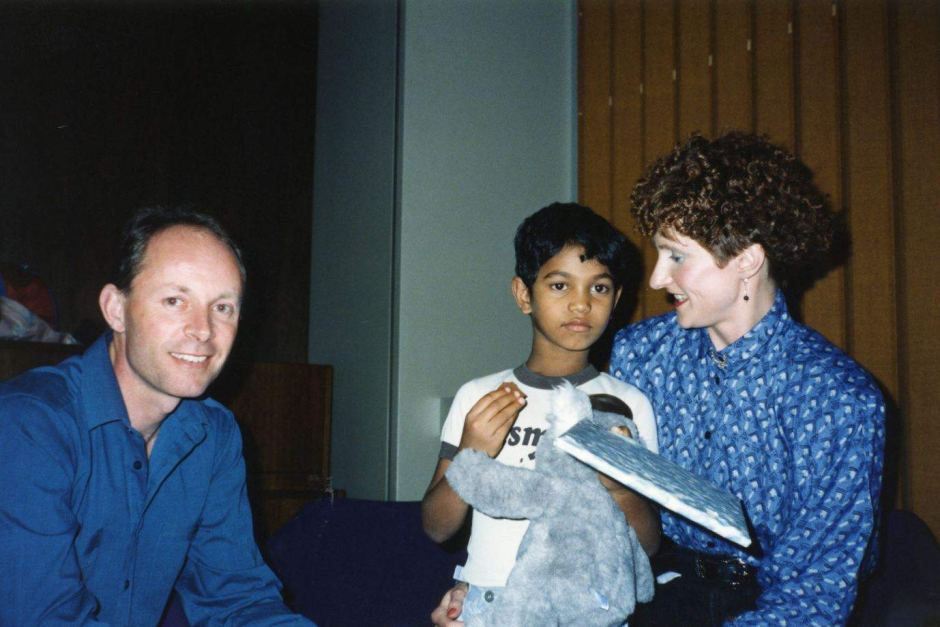

Years later, while Saroo was at college, Google Earth was released and he realised that if he could find landmarks from his memory, he would be able to find the family he had lost. After five years of obsessively searching online, following various train tracks across the vast subcontinent, he spotted a station with the water tower and tunnel he recognised – and after 25 years, found his way back home. He travelled, alone again, back to Khandwa and retraced the route he used to walk from the train station to his home. When he arrived there he found that the shack, shared by a family of five, was empty and crumbling. He showed a picture of himself, like the one featured here of him as a young boy, to people passing and somebody said: “Come with me, I’m going to take you to your mother.”

Twenty-five years after he had disappeared, Saroo was reunited with his birth mother. Although his family had moved away, she had wanted to stay close to her old home in case one day her son would return. “My mother described her reactions better than I ever could mine: she said she was ‘surprised with thunder’ that her boy had come back, and that the happiness in her heart was ‘as deep as the sea’.

The ultimate driving force was knowing if my family was alive“The ultimate driving force was knowing if my family was alive,” Saroo says. “Seeing their faces again and telling them I’m okay – and knowing that they’re okay as well. Who else wouldn’t want that too? It was about having closure, and there is closure now.”