“When making films you need to be aware that people have short attention spans.” So says a character in the Swedish comedy The Square, one of a duo a young marketeers who craft YouTube snippets calculated to shock for maximum viral impact for big corporate clients.

I suspect we’re invited by director Ruben Östlund to view the sentiments behind this quote running counter to the logic of his own film. The Square, which won the top prize at Cannes, is just over two-and-a-half hours long; much of it is filmed in long, unbroken takes, and it’s set in the rarefied world of Stockholm’s contemporary art world with gags that demand a working knowledge of conceptual land artists. From this, you’d suppose Östlund credits his audience with at least some staying power.

It’s true: The Square is a fiercely witty comedy that requires and rewards patience from us. Some of the best gags are exquisite slow-burners or pay out only through careful scrutiny or stark repetition.

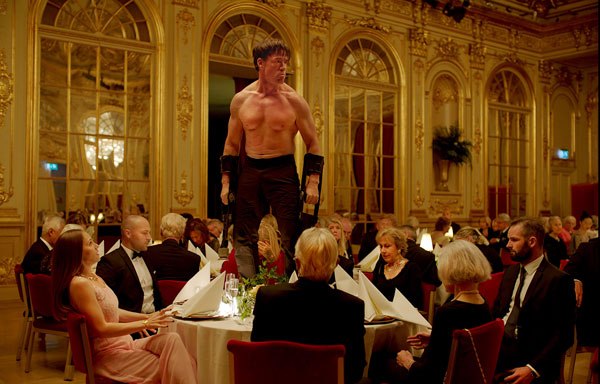

And yet the movie is also underpinned by Östlund’s unerring knack for provocation, a provocation that isn’t so different from those young digital punks. Charting the misfortunes of Christian (Claes Bang), the suave chief curator of that museum, The Square is primed to manufacture outrage; it’s a series of excruciating spectacles that confront the settled conventions of the art-world denizens it’s set among.

This makes for some strong, indelibly crafted moments of cinema, but there is also something blunt and ill-conceived about The Square’s central thrust. Like Östlund’s earlier films, including his recent Force Majeure, there’s a satiric edge to proceedings, here aimed at the airy echelons of the modern art world. With Christian as our guide, we are introduced to mounds of gravel framed as an important work (later hoovered up by cleaners) and to a public installation whose meaning remains bewilderingly opaque throughout (and from which the film takes its name).