Who says traditional advertising is less effective than its online equivalent? Whatever else, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri advertises the blunt potential of marketing, the old-fashioned way. Gift shop worker Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand) has a message to impart to her fellow residents in the Midwestern town of Ebbing, more specifically to this small community’s well-respected lawman, Chief Willoughby (Woody Harrelson). Her daughter was raped and murdered less than a year ago, and Willoughby and his team have yet to find any suspects. So Mildred rents out those rickety yet imposing billboards on the outskirts of town, and on their flaking facades she pastes this punchy message: RAPED WHILE DYING; AND STILL NO ARRESTS; HOW COME CHIEF WILLOUGHBY?

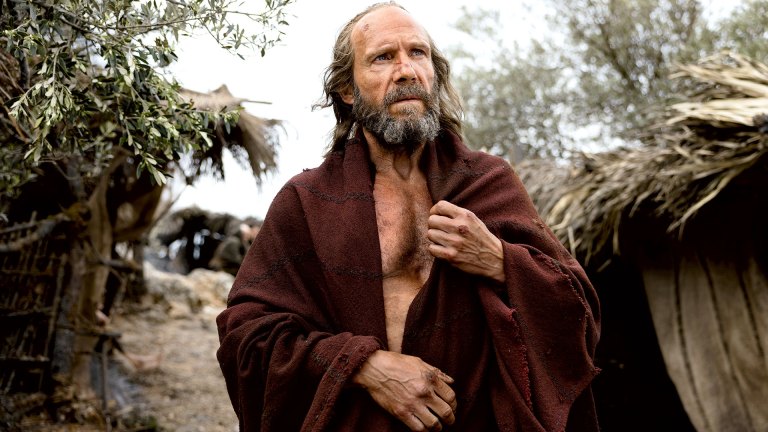

I suppose Mildred could have got the same point across via social media, but I doubt a Facebook post would have had the same consequences. Willoughby (a decent, conscientious figure, played with gritty affability) does apply some renewed vigour to the case. But he’s saddled with an incompetent colleague, Dixon (Sam Rockwell), and is facing a terminal cancer diagnosis.

The townsfolk resent those billboards too, and Mildred, an abrasive figure at the best of times, finds herself alienated. Over the course of just under two hours, those billboards will have directly or indirectly caused two major instances of arson, a terrifyingly ugly act of sustained police brutality, and one of the most unglamorous bar fights since David Cronenberg’s 2005 movie A History of Violence.

McDormand’s performance is a tour de force that many are touting as a strong Oscar contender

Three Billboards is about one woman’s desperate campaign for justice, and it’s animated by the grief and the fury that McDormand brings. It’s a tour de force that many are touting as a strong Oscar contender, and writer-director Martin McDonagh is lucky to have her. Her flinty determination isn’t especially likeable: witness her chilling response to Willoughby’s confession that he is dying. But frequently the tough front cracks, and McDormand offers poignant glimpses of Mildred’s pain.

Sam Rockwell is terrific too, as the dim, racist Dixon. Rockwell has fun playing someone clearly promoted beyond his abilities – his domestic set-up in a rambling house he shares with his overbearing mother feels like something Tennessee Williams might have concocted if he’d written a TV cop show. But there are hints of a more developed inner life and the film is at its most moving when it’s engineering his rehabilitation: galvanised by Mildred, he begins to investigate the case, and acts with the discernment of a good detective.