Most spectacular is Pinocchio himself. Makeup maestro (and Lancashire lad) Mark Coulier, a veteran of the Harry Potter films and two-time Oscar-winner, created a completely convincing walking, talking carving, as well as a supporting cast of colourful characters. The puppet looks solid, like you’d get a splinter if you slapped him (which you often want to do), and his face collects scratches and marks as the film goes on. Nine-year-old Federico Ielapi endured three hours in the makeup chair daily to transform from a real boy to a puppet who wants to become a real boy. And wooden acting in this case is the highest possible praise, his naive Pinocchio simultaneously self-centred yet vulnerable.

Roberto Benigni feels born to play a humble, pathos-dripping Geppetto, overwriting his own performance as Pinocchio in a misfire 2002 version when he was touching 50. Benigni wrote and directed that film after the Oscar success of Life is Beautiful meant he could pick any project, and he chose the icon at the centre of Italian culture.

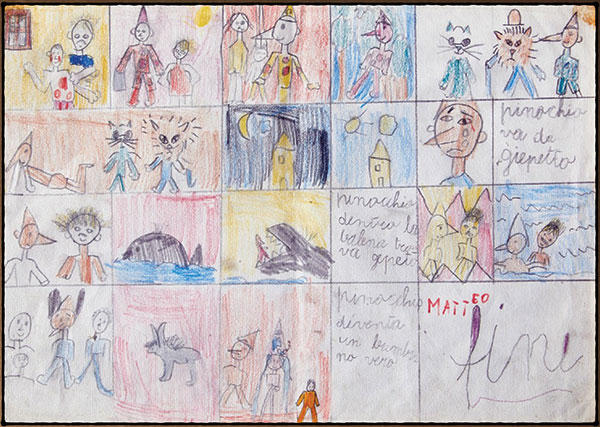

Pinocchio is Italy’s mascot. Souvenir stands sell little wooden toys, never the Disneyfied version, but based on the original illustrations from Carlo Collodi’s book, the most widely read work of Italian literature, which began in serial form in 1881. But because international audiences are more familiar with the 1940 animation, being exposed to the original packs a punch.

Returning Pinocchio to his roots was Garrone’s ambition.

“Pinocchio is based in a poor part of Tuscany. Poverty is the main character, in a way. And so, for me, it was important to go back to that world. It’s a story that tries to teach to the kids – and, of course, not only kids – how dangerous the world around you can be. It’s a story where sometimes you laugh, some other moments are dark because it’s important to show the consequence of making wrong decisions. We live in a world very dangerous, violent, and full of risk.”

In the film, Pinocchio catches fire, is kidnapped, robbed, hung (quite graphically), transformed into a donkey, enslaved, tied to rocks and tossed into the sea, miraculously escaping only to be swallowed by a whale.

This is why it is a story best told by an Italian, Garrone says. Pinocchio’s encounters are comparable to the horrors found in Dante’s circles of hell. Like the source material, the film is picaresque with humour and broad characters drawn from commedia dell’arte. Many adaptations (Disney’s inevitable ‘live action’ remake is in production and Guillermo del Toro is making a stop-motion version for Netflix with Ewan McGregor and Tilda Swinton) soften the edges.

When Pinocchio *spoiler alert* finally becomes a real boy, it’s not because of a conscientious cricket (killed by the precocious puppet by the end of chapter four in Collodi’s book) but due to the suffering he has to go through.

“It’s very important,” Garrone says. “Through suffering you can grow, really understand. It’s sad that it’s true. But I can see in my personal life I learn after I went through something, not before. I understand many things because I live the experience.

“Pinocchio pays the consequence of what he does,” Garrone says. “Sometimes in our society people who do whatever they want without paying the bill – but not Pinocchio.”

Learning to be selfless instead of selfish is also key – and the moral at the heart of the story is none of us are truly human unless we become kinder to others.

“The redemption of Pinocchio, how he learns to live not only for himself but for the father is important. At the beginning Geppetto does everything for him, at the end it is he that helps Geppetto. So it’s a circle.

“That’s why Pinocchio talks about the past, talks about today and talks about the future. It talks about the archetype of human beings, of us.”

Pinocchio is out now in cinemas