It was 1978 then, and 1980 when I graduated from high school. New Jersey was a wonderful, hard-working blue collar place to grow up in. And although both of my parents worked five or six days a week, there was never a lack of food or clothing or school, we were given the great gifts of that comfort. I was born during the John Kennedy administration. So my parents married under that kind of hope and aspiration and they instilled it in their kids. It was brimming with optimism and belief in the opportunity that you could, in fact, achieve your dreams.

There was no plan B for me, ever. I can remember walking the two-mile walk to school with the guy who became my first band’s bass player. And I would just conspire as to how I was going to get a band together, how I was going to play in bars and eventually make it. Which to me at that time just meant keep on playing in a bar – the measurements of success change throughout the course of your life.

My three best friends, including that bass player, they joined the navy. When I got the call from the recruiting office my answer was, does the uniform come in different colours? Can I take the pants in around the ankle? I’m not sure about that haircut. My buddies joined the service because they thought, OK, this is the best way out for me. But I said: “Nah, this is what I’m going to do. I’m gonna be in a rock band”.

We would have magazines in the States. Circus magazine, Creem magazine. And inside you had these posters of the biggest bands in the world you would tear out and hang on your wall – Led Zeppelin and Aerosmith and Alice Cooper. But on top of that, and maybe more important, 25 miles away from where I grew up was Asbury Park. And there were guys there singing songs from whence I came. Playing their own music. And although they were not in those magazines, and they weren’t big by definition, it was them who made the impossible possible.

Although all those guys were much older than I was, they were singing songs about where I were from, and performing in places where I could see them and meet them. And that was a big part of the inspiration for me, it made my dream tangible.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

I think regarding my parents, I am a combination of both the good, the bad, and the indifferent. As I think we all are, but it takes a while for you to be able to see that. And it takes a longer while before you can say that. It’s really helped to shape who I am now as a man and as a father. Because you have your two halves, and you meet your wife or your significant other and they bring their two halves so you’re four quarters and all of those inspire your kids.

What I got from my parents was the ability to make the dream reality. They always instilled that confidence in their kids which, in retrospect, I realise was so incredibly valuable. Because even if you truly weren’t any good at your craft, if you believed you were, you could work on it. As I got older I realised that was a great gift that I got from my folks. They truly believed in the John Kennedy mantra of going to the moon. “Yeah, of course you can go to the moon. Just go, Johnny.” And there I went.

The first talent show my parents came to see me play I was so terrible they wanted to crawl under their seats with embarrassment. But they saw my passion and my commitment. So when I was just 17 they let me play in bars till closing time and they always said, well, at least we knew where you were. They were always supportive of me, which in retrospect, was incredible. Because I could get home at one or two in the morning, and have to still be in school by eight o’clock. They just said, show up on time for school, you know that is your responsibility, but pursue your dream.

They never once said you can’t go to the bar. They knew I wasn’t going there to fuck around. I was going there to do the job. And I didn’t have the responsibility of a young family or paying the rent or anything like that. So all those things worked out. Though of course, it wasn’t like I was 30 and still going to the bar. By the time I was 20 I had written Runaway and it was on the radio and by the time I was 21 I had a record deal. So there wasn’t the need for my parents to have a sit down with their 35-year-old son who was still playing in a bar in Santa Barbara saying “I’m gonna make it.”

I think the beautiful thing about being naive and being a kid is thinking that you know a lot, even if you don’t. There’s a certain grace in naïveté. And it’s beautiful, because it allows you to constantly put yourself out there and every step of the way dare to say what you want, and dare to do what you want. Because that is the greatest gift of all, to not be regretting decisions you could’ve, should’ve, would’ve made, had you had the courage. Each step along the way, I was cocky and confident and single-minded.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

I couldn’t choose just one moment in my life to go back and encourage my teenage self with. I could take a time-lapse, 60-second warp-speed video of the whole thing and then at the end of it just have it go ‘pop’ and look at that kid and say, it happens. But that would be too much for any kid to handle. Half of the fun is the roller coaster of a real career, and a real career for me doesn’t come into play until you’ve done it for 20 years.

It’s about the ebb and the flow. You have to have successes, and you have to have doubt, and you have to have failure, and you have to have tears that you shed so that when you come through it you can honestly say, now I understand. If it all happens early and quickly there’s probably not the same appreciation. You could be like a firecracker, just have a big quick pop and it’s over. Or the ebb and flow of a real honest-to-god career with all of its pain and joy. I’d rather have that.

The biggest mistake I made in my life is that I didn’t take enough time to stop and look around and enjoy it. I was always so focused on the next step, then the next and the next, that it cost me a lot of great memories. And it caused a lot of sleepless nights that weren’t warranted. It’s my biggest regret. The one thing I would tell the younger self is, enjoy it more, relax. It’s gonna have ups and downs but keep the faith.

When I hit that dark period a couple of times throughout my career [long periods of non-stop touring drove him to depression], losing people along the way [long-time band member Richie Sambora left the band in 2013; Jon has said there’s not a day when he doesn’t wish “Richie had his life together and was still in the band”]. There were times it was deeply dark, and deeply hurtful and I wouldn’t wish that on myself, ever. But it’s a part of life. You come through it. It doesn’t make you feel good. But it makes sense. You know, there’s reasons why people get off the ride. And it’s probably so that you can continue on that journey.

When you’re in the middle of it you don’t believe anyone who tells you you’re gonna come through it. But when you do, the scars are there and you can look at them and justify them and look back on that darkness from the light. And then you can say, OK, I got through it. And in essence, I have to admit, it was worth it. I wish it was all pretty, but maybe if it was all pretty I wouldn’t have gotten this wisdom or this deep appreciation for who and what I am today.

I had closure with everyone important in my life who’s gone now. I was very lucky in that sense. But I wish I could have time, as a man, with my grandmother and my grandfather, who died when I was 13. And a guy called Jerry Edelstein who was technically called my attorney but was way, way deeper than that. He’s the godfather of my daughter and was my closest confidante in the world. I miss him terribly every day.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

If I could go back and re-live any moment in my life the first thing that comes to mind is the birth of my kids. Because that was such a miracle. The birth of a human that you’ve helped create – that’s probably the biggest, most unbelievable thing that I could ever want. To touch the hand of God, that’s as close as you ever come to that.

I remember coming home with Stephanie, our first, and thinking I have a daughter? I never even had a sister. That was daunting. We were in uncharted territory to say the least. Everyone comes to the hospital to visit and they bring flowers and balloons, and they drop your bag off and the mommies lay down in the bed with the baby, and then you’re like, oh my god. Now what?

And driving the first baby home you’re scared stiff, you’re like, everybody get away from this car! Just move away. And then we came home and it was like, where’s the manual? How do we work this thing? There’s just the two of us alone in the room going, holy shit. We were so grateful that she was healthy but we were scared shitless. Of course by the time you get to the fourth baby, you’re dragging it into the parking lot by its arm, saying, ‘Whatever. Strap yourself in, you’ll be fine.’

The greatest joy that I get, when I’m not in the midst of being Jon Bon Jovi on some stage, is when we spend a day at one of the soul kitchens. Because you leave there and you know that you’ve really truly done good. You leave feeling a sense of accomplishment on the day. And it’s really, really satisfying. It’s just glorious.

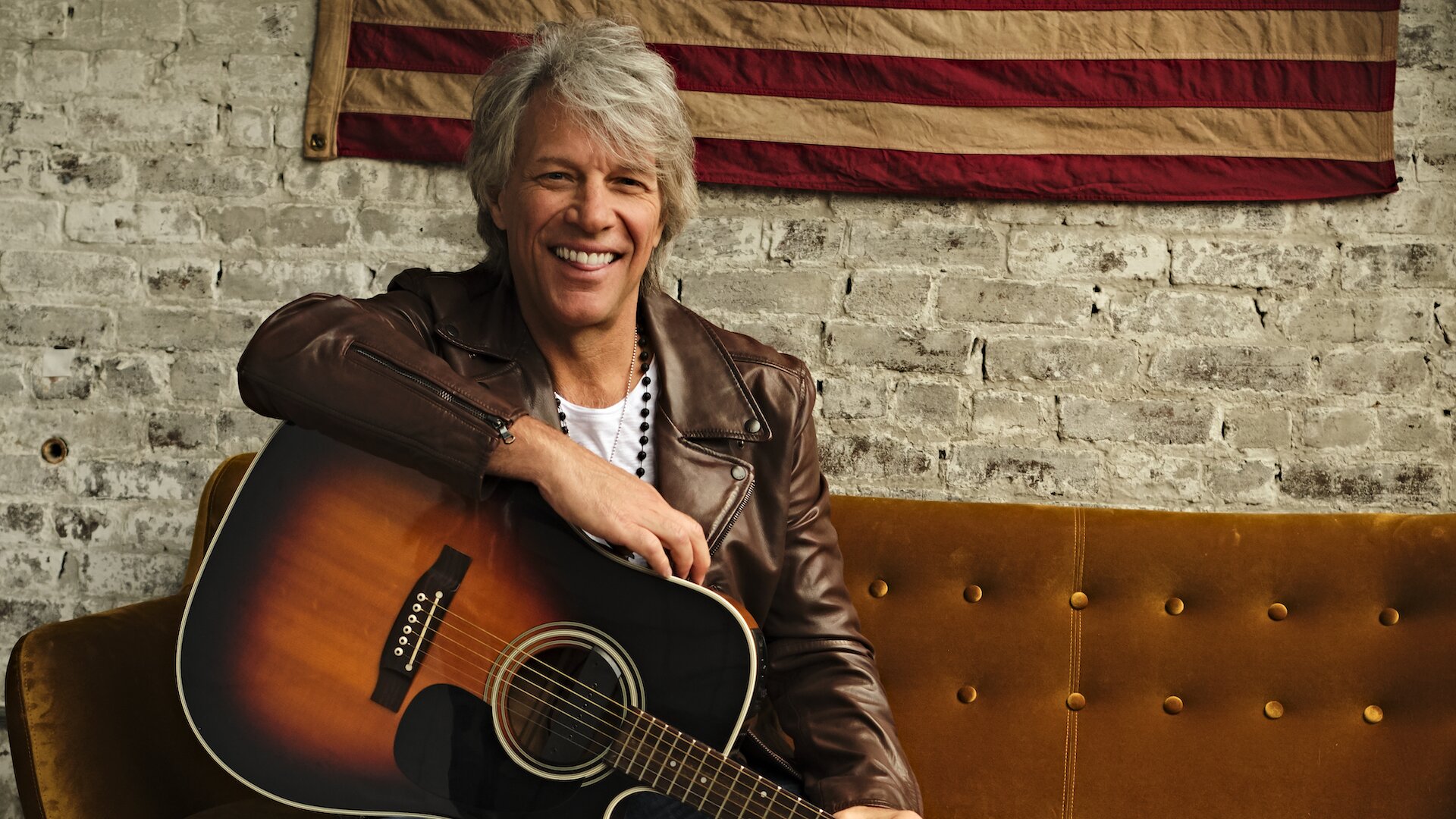

Bon Jovi’s new album 2020 is out now on Island.

Interview: Jane Graham @Janeannie

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

More than 1,000 Big Issue vendors are out of work because of the second lockdown in England. They can’t sell the magazine and they can’t rely on the income they need.

The Big Issue is helping our vendors with supermarket vouchers and gift payments but we need your help to do that.

Please consider buying this week’s magazine from the online shop or take out a subscription to make sure we can continue to support our vendors over this difficult period. You can even link your subscription to your local vendor with our new online map.