As well as their musical legacies, some composers have left behind highly quotable aphorisms. Bartók is as famed for his string quarters as he is for his observation that competitions are “for horses, not artists”, while Debussy’s “works of art make rules; rules do not make works of art” is a snappy phrase for the ages. Some of these attributed sayings relate to particular music styles: John Cage, the avant-gardist famous for 1952 installation piece 4’33” – in which performers do not play a single note – is claimed to have said: “I can’t understand why people are frightened of new ideas. I’m frightened of the old ones.”

Like “let them eat cake”, several of these gobbets may well be mistranslated, or even mistranscribed by unreliable journalists (perish the thought!). But the real problem is that not all big ideas can be distilled into a pithy sentence: Pierre Boulez is quoted as claiming the best solution to the problems facing opera would be to blow up the opera houses (a strategy coming soon from Arts Council England, possibly).

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

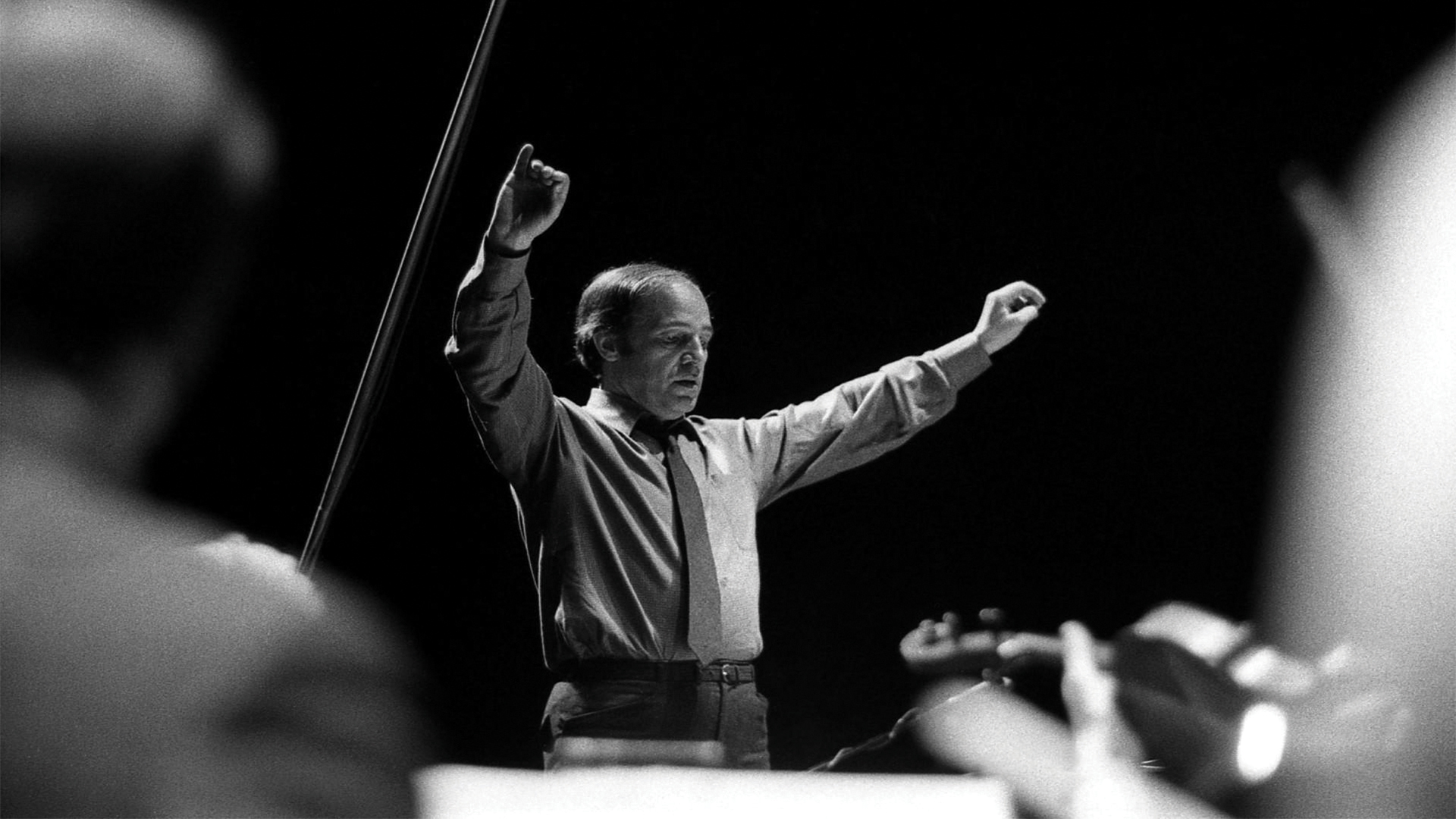

Pierre Boulez (1925-2016), whose centenary is celebrated this year, was a conductor, composer and provocative musical thinker. He’s often defined by his seemingly throwaway comments. As well as the opera house suggestion, Boulez wrote that any musician who had not experienced the necessity of the 12-tone system (a compositional technique based on rows of 12) was “USELESS”, with a preference for caps more commonly associated with below-the-line trolling than musicology.

Comments like these – or his observation that it is not enough to deface the Mona Lisa, it should simply be destroyed – are part of a broader, more reasoned argument that art needs to unburden itself from history in order to achieve its fullest potential.

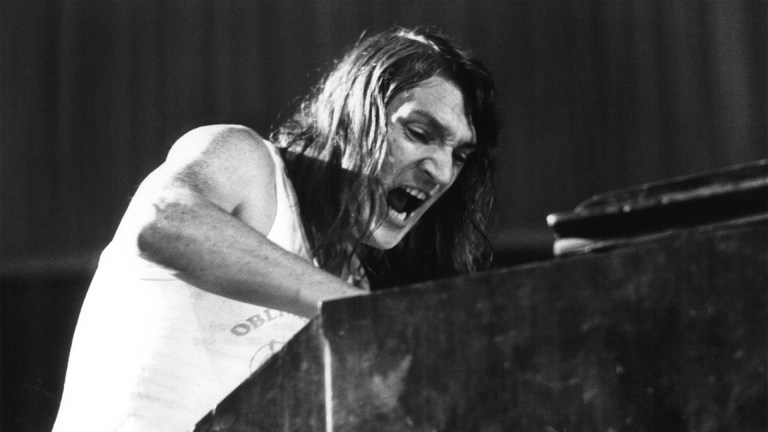

Such theory resulted in music that is exciting, experimental and, despite (or, as Boulez might say, because of) strict compositional parameters, highly imaginative and compelling. Like visual artists in the postwar period, Pierre Boulez’s music has a sense of a complete break from what had gone before. He corresponded and argued with colleagues during this time about what classical music could and should be; the exchange of post with John Cage between 1949 and 1954 is the inspiration behind The Boulez/Cage Letters, London Sinfonietta’s concert drawing on the similarities and differences between the two composers (The Purcell Room, London, 9 March).