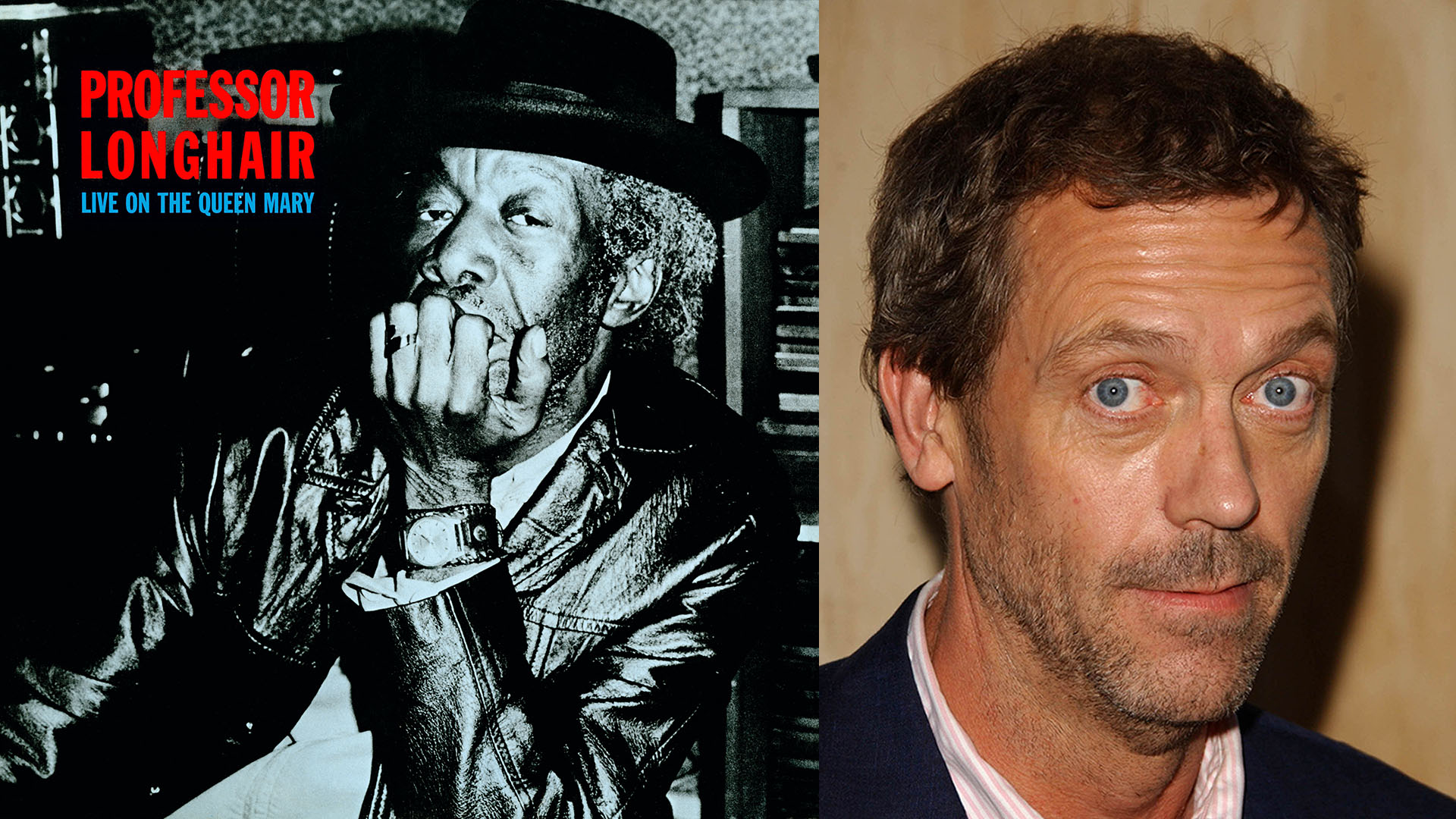

Originally released in 1978 on Harvest Records, Professor Longhair’s Live on the Queen Mary documents a legendary performance from the Venus and Mars album release party thrown by Paul and Linda McCartney and Wings in 1975.

On the day of its re-release across digital platforms, on CD and on newly remastered 180gram vinyl LP, we exclusively bring you this fascinating and emotional foreword by Hugh Laurie.

“FESS”

Professor Longhair was born Henry Roeland Byrd in Bogalusa, eastern Louisiana. And is there any part of that statement that isn’t already musical? Yes, Bogalusa has four beats, against Bethlehem’s triplet, but the name still has a holy fizz to it. The town was thrown up at the beginning of the last century to feed the local sawmill, a vast mechanical dragon that chewed its way through half a million acres of virgin pine forests across Louisiana and Mississippi. Needless to say, it chewed up some people too. In 1919, a ferocious union dispute grew into The Bloody Bogalusa Massacre, and forced the Byrds towards New Orleans.

I should let you draw your own religious parallels at this point. But it feels dishonest not to say that New Orleans is my own private Jerusalem, and had been for many years before I ever went there. In my teenage mind, the city existed as the birthplace of a divine force on this earth, born in slavery and occupation, and spread through the teachings of…well, New Orleans has had more prophets than it knows what to do with.

He would cannibalise them, taking hammers from one, dampers from another, strings from a third,

The young “Roy” Byrd, so the story goes, learned to play piano on a succession of broken instruments he found abandoned in the back streets of New Orleans. (This was a time, remember, when there were more pianos in the US than baths. Pianos were, literally, litter.) He would cannibalise them, taking hammers from one, dampers from another, strings from a third – an almost perfect parable of his later musical genius – and bring them back to life. There were often keys missing in the middle octaves, where the wear is heaviest, and perhaps that had something to do with the development of his astounding rhythmic feel. I say astounding because, at that time, popular music swung, and would swing for the next thirty years or more. That was just how you did it, how your forebears did it, how music was supposed to sound. Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Cab Calloway – all of these giants were swingers, and their audiences grew to hear and love music that way. But Henry Roeland Byrd – he was still some way off his elevation to The Chair – heard something very different.

He called it his gumbo, and I’m absolutely not qualified to list the ingredients. But I can tell you how they taste to me, if you’ll allow it. There’s a Jimmy Yancey left hand, straightened out to allow for Bogalusa instead of Bethlehem (four seats at the bar, stand back all you gently swinging triplets), then a pushing and pulling of those four syllables (hey, ga, shuffle up nice and close to lu), until spaces appear, gravitational rhumba holes that pull the heart

out of your chest. To my ears, then and now, this is music that moves, struts, even marches. (For a while, Byrd had earned a living in a dance trio alongside Champion Jack Dupree and Redd Foxx, and how many kidneys would I give to have seen the three of them together?) There’s a Latin sauce in there too, close to what Jelly Roll Morton called ‘The Spanish Tinge’, and a splash of calypso in the right hand patterns, with sixths and major sevenths suddenly punching you on the shoulder, rousing you from whatever melancholy you thought you were entitled to.