We were in the grip of the recession and money was tight for everyone, even the most well-heeled of the commuters who flowed past us each evening. Every pound was precious – so much so that tempers got frayed among those of us who were competing for that scarce loose change. In the week before Christmas that year I almost ended up in an altercation with a ‘chugger’.

He was standing on my official pitch outside Angel Tube station entrance shaking a large bucket around. To judge from the dodgy-looking laminate badge he was wearing and the fact that his bucket wasn’t sealed as it was supposed to be, I was pretty certain he was working for a bogus charity.

When he almost stepped on a terrified Bob I admit I lost it. We had to be separated by a community police officer. Such moments were understandable. We were all living on a knife-edge.

I lived in constant fear of my electric or gas meter making the dreaded beeping noise that told me I’d run out of credit. Bob and I often had to sit at home, wrapped under the same blanket, snuggled up close together for warmth. As usual I had stockpiled the few Christmas treats I allowed myself in my small fridge and knew that if I lost electrical power it would all get ruined.

I wouldn’t be able to replace it all. Christmas too would be ruined. Of course, for many it was even tougher. At least I had my assisted housing flat to go home to.

It was grim. And yet, against all the odds, that Christmas proved an unforgettable one for Bob and me. How? Well, it was the year that, rather miraculously and against all the odds, I discovered the spirit of Christmas alive and well on the streets of London.

When he almost stepped on a terrified Bob I admit I lost it. We had to be separated by a community police officer

Bob and I had established a loyal following at the Angel. Our regular customers were always amazingly generous, showering Bob with treats – from catnip-laced toys to blankets and scarves. They were also magnanimous with their donations for the magazine.

That year, however, their kindness shone through more than ever. As if sensing how tough a December it had been, many had given me Christmas cards containing a little extra for the holiday period. Almost each of them had included a heartfelt message for Bob and me. Hunger and desperation aren’t always conducive to deep, philosophical thoughts. Yet that Christmas, particularly after receiving so many gifts, I found myself dwelling on my circumstances, and the people with whom I interacted on a daily basis.

It was one night as Bob and I were travelling home on the bus that I started to see the light. Each card had touched me deeply but I’d been so busy living from hand-to-mouth that I’d not had the time to thank people. It was pretty selfish of me really but then living on the streets does that to you. It is very much about looking after number one.

On the bus that night I decided to change that. I dived into my local convenience store and grabbed a pile of Christmas cards, which I then proceeded to hand out not just to my regulars but to everyone who was kind enough to buy the magazine.

I’d never done this before. It had an amazing impact on me. It wasn’t just the boost that the smiling, often surprised expressions on people’s faces provided me with as I handed over a card. It made me appreciate that, even for a Big Issue vendor, there is as much pleasure in giving as receiving.

It was the beginning of a remarkable few days. A few days later, having discovered there were no more copies of The Big Issue for us to buy and therefore sell on the street (yes, that’s the way it works), a group of us vendors got together for a quick drink off Camden Passage.

It was no different to all the other Christmas parties and get-togethers that were happening all over London – and the rest of the country. Like a bunch of city traders or nurses or bricklayers, we shared our work stories over a festive drink, stamping our feet in the cold as we sipped our beers (the pubs weren’t too keen on a bunch of dishevelled-looking vendors, I seem to remember. They certainly wouldn’t have welcomed one with a ginger cat on his shoulders).

Again, it gave me pause for thought. Living on the streets is a very lonely existence, you feel isolated, invisible. Sharing a drink with my fellow vendors countered that feeling, it made me feel I was part of something, that I wasn’t alone. It also made me realise I had much for which to be grateful. That was a feeling that deepened as Christmas Day drew nearer.

They’d looked at me as if I was something unpleasant that had become attached to their shoe

Two days before Christmas I had a couple of encounters with what I can only call ghosts from my Christmases past. One came when I saw a guy sleeping rough at the exact same spot that I’d slept one Christmas, near Covent Garden. I gave him a few quid and sent him on his way to one of the refuges that I knew were open that year.

Another came when I was approached by a shady character who, it seemed, recognised me from my drug-addicted past. Bob has a great radar for spotting people who are out to cause us harm. When the guy tried to foist some stuff on me he let out a loud eeew sound and scratched him with his claws.

Both incidents underlined a simple truth. What’s that old saying… “The wise man is someone who doesn’t grieve for the things which he doesn’t have but is grateful for the good things that he does have.” I didn’t have much but it made me think about the blessings that I needed to count.

Slowly but surely all these things combined to create something that was close to a miracle. They made me feel a part of London’s Christmas. They made me feel a part of Christmas, full stop. That hadn’t always been the case. I’d had something of an aversion to Christmas since my childhood. I’d associated it with unhappy times. I’d grown to dread it. My early days on the street had only exacerbated that feeling of disconnection, of being an outsider, a non-person.

I remembered one Christmas in particular when I’d slept rough. I’d got up on Christmas Day and walked past a hotel where a bunch of people were toasting each other with a glass of champagne. I’d given one of them a wave, as if to wish them a Merry Christmas. They’d looked at me as if I was something unpleasant that had become attached to their shoe. It had made me feel about one inch tall.

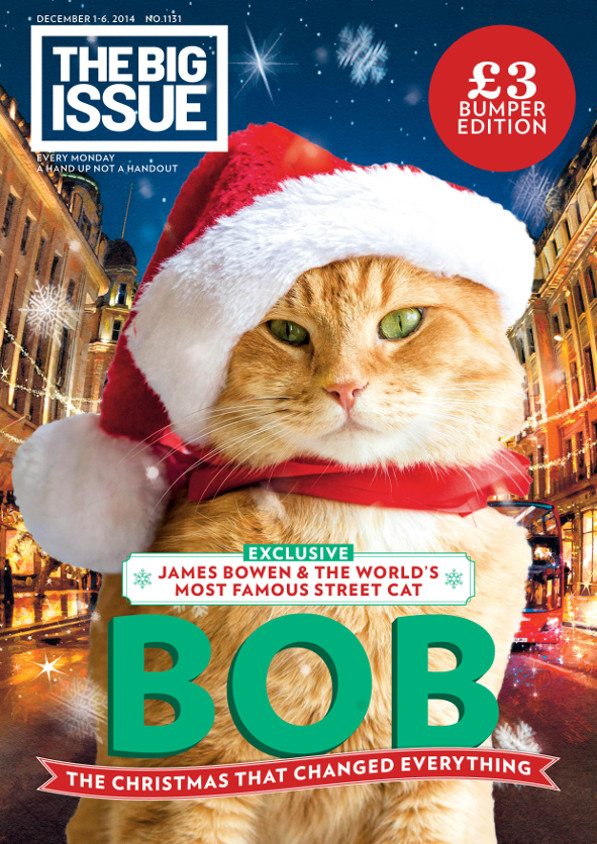

But Christmas on the street that year actually made me begin to appreciate and even enjoy it. What I could not have known was that it would be my last full Christmas relying on the goodwill of others. By the following year I’d completed a book about my life with my feline companion, A Street Cat Named Bob.

By the following Christmas, 2012, it had become a bestseller, not just in the UK but across the world – from Germany to Brazil, Norway to Turkey. In the words of John Bird, the magazine’s founder, selling The Big Issue had given me a hand up and not a handout. And what a hand up!

This Christmas Bob and I will spend the run-up to the festivities rather differently. Our latest book, A Gift from Bob, which charts the lessons we learned during that cold, cold Christmas on the streets, has just been published and we will be busy giving interviews and appearing at public signings.

Among our appearances will be a book signing at Waterstones in Islington where, appropriately, we often took refuge during that winter, with me looking through the science fiction shelves while Bob found a warm spot by a radiator.

A Gift From Bob: How A Street Cat Taught One Man the Meaning Of Christmas (Hodder & Stoughton, £12.99) is published now