Citizen Jane isn’t an especially inventive documentary. A combination of experts saying things to camera and archive footage, the film doesn’t exactly reinvent the form. But I can’t say that mattered. Within a few minutes, one of the talking-heads says something that had me hooked. An academic specialist on town-planning – the film’s less-than-sexy subject matter – explains that every two months the urban population on this planet grows by the equivalent of another Los Angeles.

Wow. That’s a lot of people, and the galloping rate of urbanisation provides blunt relevancy to this film’s account of plans to develop New York back in the 1950s and 1960s. Against a black-and-white shot of Manhattan skyscrapers in their jazzy prime, a thin black band containing the film’s title splits the screen in half, and you sense lines being drawn: the subtitle pitches exactly that, billing what follows as a ‘Battle for the City’.

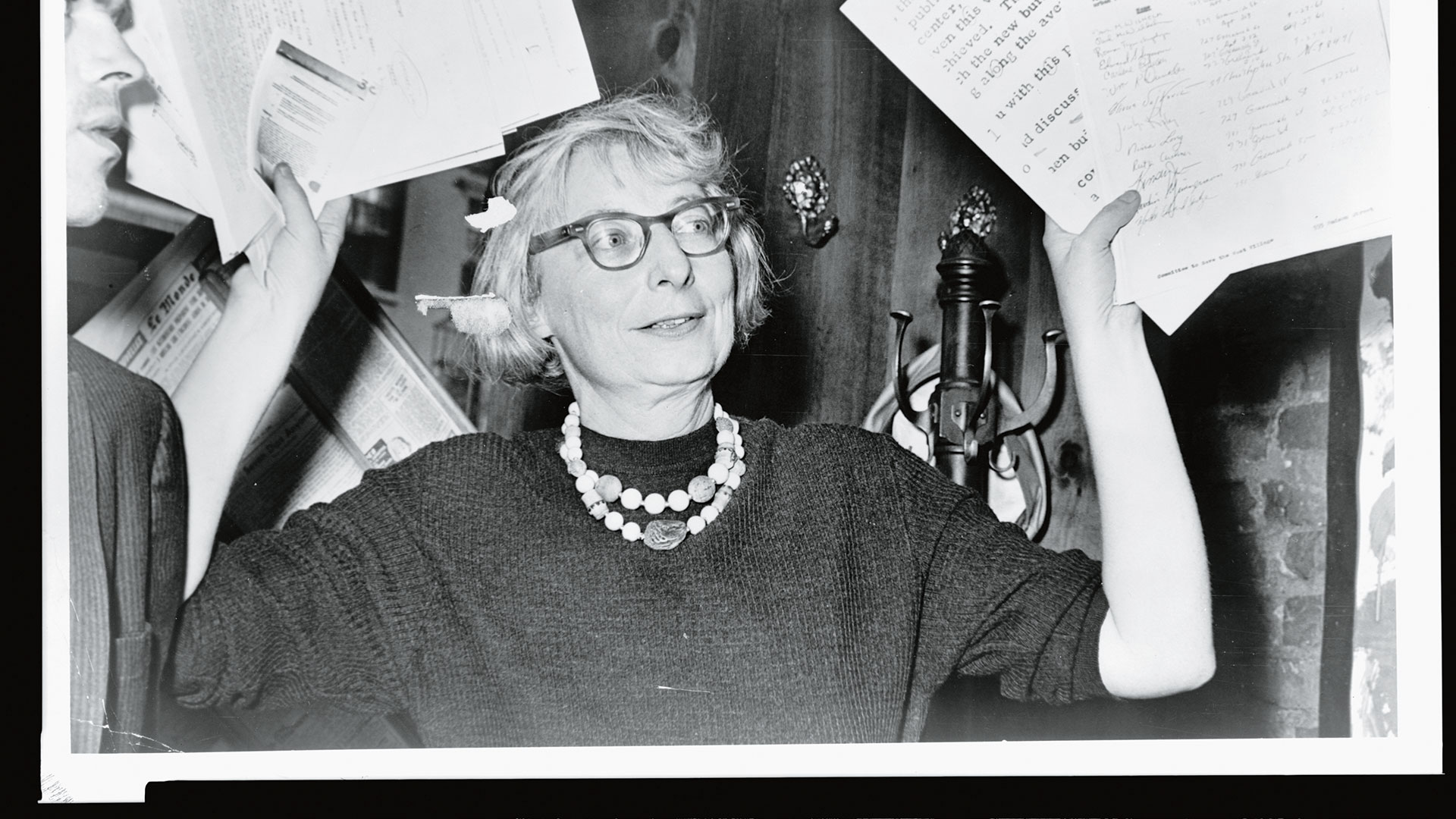

On one side we have Jane Jacobs, a middle-aged woman in owlish specs with a choir-boy bob who was at the forefront of defending postwar New York from the bulldozers. Opposing her is New York City’s planner-in-chief, Robert Moses: ardent enthusiast for the automobile – and for demolishing residential buildings to make way for multi-lane freeways – and vigorous exponent of architectural modernism in all its high-rise puritanism. In his cocksure alpha male assurance he makes Mad Men’s Don Draper look like a wilting wallflower.

Emerging from the well-chosen clips, Jacobs and Moses seem like opposites, but the film prefers to imply rather than dwell on any great differences. At its absorbing heart are conflicting ideas of how urban life should be organised. Moses is, I suspect, a familiar figure from any UK city – Glasgow, Bristol, you name it – blighted by postwar planning: his modus operandi is to raze to the ground parts of New York that grew over decades, in favour of anonymous tower-block residences and a tangle of highways.

In his cocksure alpha male assurance Moses makes Mad Men’s Don Draper look like a wilting wallflower.

It’s a mix of misguided utopianism and Olympian disregard for the feelings of residents, which director Matt Tyrnauer conveys with nifty elegance by way of a sequence about Le Corbusier and an extended trawl through the Byzantine world of city-hall politics in the 1960s.