On April 4 1968 on a warm spring evening a dream died. A single shot from a pump-action hunting rifle hit Martin Luther King Jr in his right cheek, breaking his jaw, bursting through his vertebrae, and fatally damaging his spinal cord. America’s most famous civil rights activist slumped back on the concrete balcony of the Lorraine Motel, the victim of a sniper – assumed to be the racist criminal James Earl Ray. The shot not only killed King but stigmatised Memphis in the eyes of millions around the world. It is a calumny that still lingers today.

At the time of King’s assassination Memphis was a city struggling to emerge from segregation, with impoverished ghetto communities stretching deep into the city’s Southside. Much has changed but much has stayed the same. Today, Memphis is the sixth poorest among America’s 100 largest cities, 66.1 per cent of residents live in or at risk of poverty and in an area along Crump Boulevard and South 4th Street, not far from the home of Stax Records on East McLemore Avenue, a third of children grow up in a single-mother household, and 80 per cent of them live at or below the poverty line.

King’s death unfairly cast Memphis as a city of hate, and yet beneath the dramatic headlines was a unique story of racial integration. Music was Memphis’s greatest love, and remarkably, it became the crossroads where a new kind of racial tolerance germinated. It was here in Memphis that the diverse threads of rock and soul came together. The city’s most famous son, Elvis Presley, was part of a generation of restless white teenagers that grew up enthralled by black music. More defiantly, Jim Stewart, the founder of Stax Records, began his career as a hillbilly fiddler from a Scottish country-dance band and yet gave life to music steeped in the ghetto. Stewart was a gnomish white bank clerk who had to learn to love black music, and who through the idiosyncrasies of time and place built Stax Records on the back of an unprecedented form of racial integration. His studio band, Booker T and the MGs, were a perfectly calibrated racial mix, composed of two white musicians and two black.

Today, Memphis has turned music into a powerful driver of the local economy. More than 11.5 million people visit the city annually, heading for Graceland, the Stax Museum and Sun Studios. Music tourism is a $3.2bn industry supporting over 35,000 jobs but while the money has transformed once-dilapidated streets in and around Beale Street, the legendary home of the Blues, less has filtered down to blighted inner-city communities.

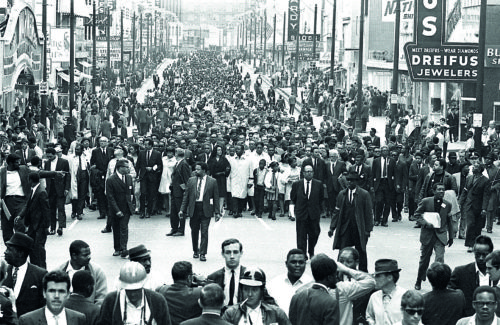

Many feared that when King was killed, the journey would stall and that the dream of civil rights would be “a dream deferred”

The city’s tourist economy has been strengthened by the recently renovated National Civil Rights Museum, which sits on the site of the old Lorraine Motel, where King was shot. It is an astonishing visitor experience – taking tourists on a journey from slavery to the multiple conspiracy theories that still surround King’s death to this day. In a chilling end-sequence, visitors queue to huddle into an old rooming-house bathroom where the fatal shot was fired from. The perspective down to the motel balcony where King was standing when he was shot makes the visitor feel complicit in the killing. It is a rare moment when a museum is more powerfully realised than a feature film.