Without a source of income the bank repossessed her house. She then stayed with a friend for a while until they ended up losing their home too.

“When Shedia opened I decided I would do it,” she says. Maria is also a guide on another Shedia project, Invisible Tours. She guides visitors around an alternative side of Athens, including the increasingly vital soup kitchens and the homeless shelter where she sleeps. Though she is not staying there for much longer. “In one or two months I will be moving into my own apartment,” she beams.

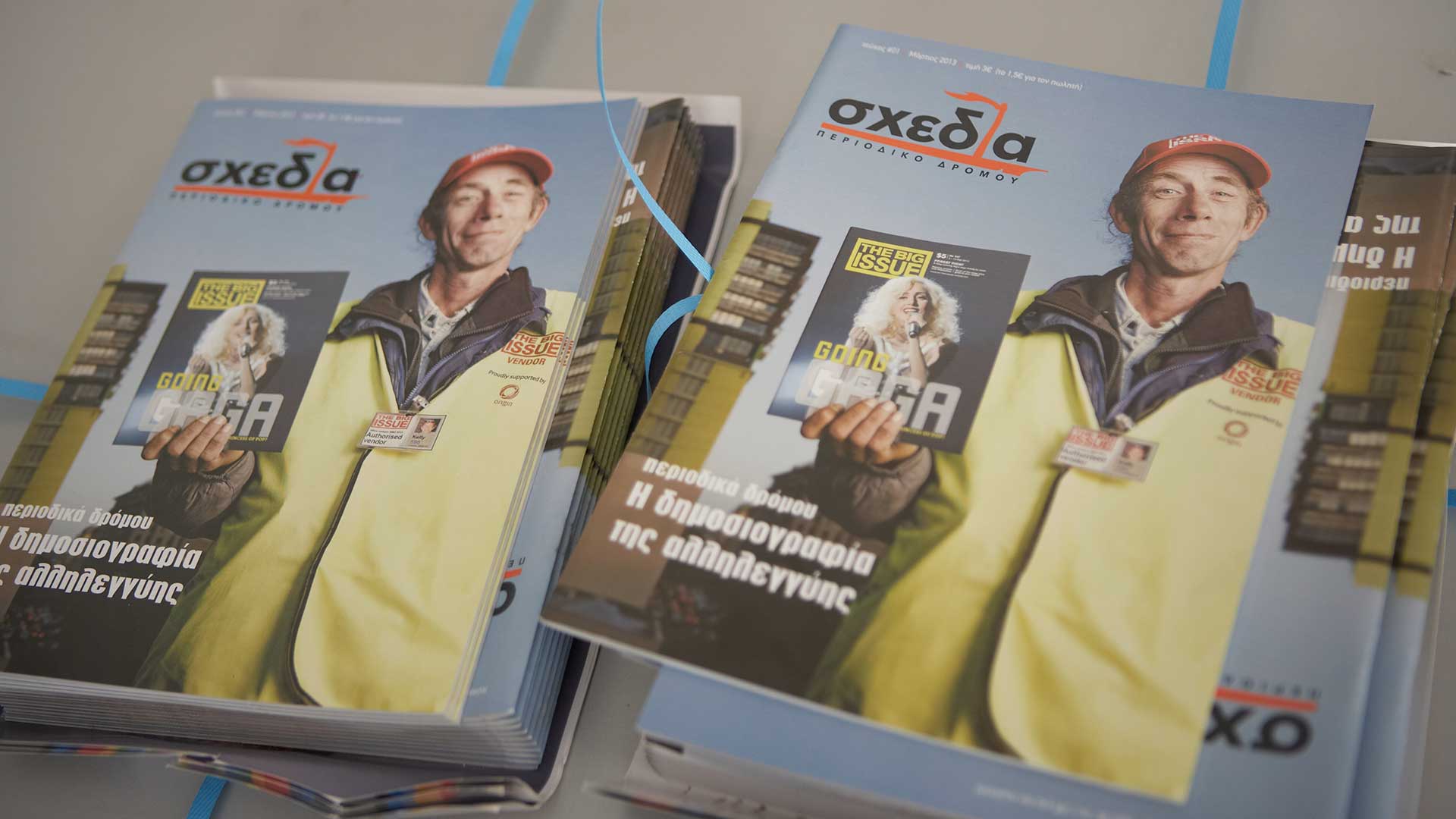

Shedia celebrates the fact that around 20 of its sellers have been able to move off the streets or from sheltered accommodation into their own home paid for through magazine sales. However, as the banks closed and cash withdrawals were limited to €60 per day, Chris was worried that his vendors’ livelihoods would be hit.

“The day after the referendum was announced we were very concerned about the vendors being able to sell any copies of the magazine given the financial circumstances. There has been a small decline but nowhere close to our fears. Sales have fallen 20 per cent [from a circulation of 20,000 per edition], but given the whole market of the country has collapsed, it is very reasonable. Shedia readers are regular people, everyday people. They still believe in love and solidarity and this is expressed through interaction with our vendors.”

Chris introduces another vendor, Despina Merkouri, who was previously a market research supervisor. She was laid off as the older employees were replaced by younger workers on temporary six-month contracts.

“I knew Shedia was a good magazine because when I was able to buy it I bought one,” she says. “If you are over 35 to 40 years old it is almost impossible to find a job. I decided selling Shedia is my way in life, I’ll stay alive this way.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Despina explains that her customers are not only those with secure jobs. Even unemployed people would buy the magazine to help others even worse off than themselves. Many would receive support from their relatives who live outside of Athens, but because it is risky to transfer money through banks, a lot of people are being forced to return to rural villages and those left are unable to buy Shedia as regularly.

Shedia readers are regular people, everyday people. They still believe in love and solidarity and this is expressed through interaction with our vendors

“They pass before us with sad eyes and say I’m sorry,” Despina explains. “It is difficult now to sell the same amount of magazines as we did before, but there are a lot of people buying even though they have little. I remember the first days the banks closed, people were paying us with small coins – five cents, ten cents – that meant a lot. They were paying from their nothing to buy the magazine and that is gives us strength and courage and hope.”

Shedia vendors sell on pitches throughout Athens, on the same streets and squares where frequent demos and rallies are held, either in support of or protesting against the Syriza-led government and/or European Commission. This gives those squeezed tightest by the grip of austerity a unique view of the situation.

“You hear conversations about the political situation, the Grexit, about what is going to happen,” Despina says. “At this time, a big change would be – let’s use a polite word – painful. It would be all too sudden and that’s what is scary. If there was one year’s preparation for a Grexit, that would be easier. It would certainly be less painful.

“Each day we hear about deadlines and each day we live the same panic, though not as much as before the referendum. Now people say ok, whatever happens… I am not a political analyst, but I do not think there will be a Grexit after all.”

The referendum called by Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras (above left) was widely viewed as a Yes/No vote to leave the euro and possibly the European Union. The world was shocked when the result overwhelmingly rejected the bailout conditions being offered, but Chris was not surprised.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“If you have three million people living under the poverty line and 30 per cent unemployment, why is it a shock?” he says. “If you don’t have any money it doesn’t matter if it’s the drachma or the euro, you still have no money in your pocket. Many people are fed up with our European so-called partners. They just want to suck our blood and people don’t want their blood sucked. You hear more and more people say, screw them, let’s go back to the drachma.”

But, many would argue, Greece borrowed a lot of money and therefore needs to pay it back.

“The media says Greece is to blame – don’t buy into it!” Chris says. “The Greek people have the longest hours per week in Europe, check the figures. Everyone agrees the debt repayments are not sustainable. What is this debt anyway? Where did the money go, to the Greek people? When did our European partners realise they were dealing with corrupt governments for the last 40 years and a lot of money was getting lost along the way? At the time of the global recession? Oh, it took them a long time, I wonder why. It is political bullying.”

“It is not just bullying, it is great bullying,” Despina emphasises.

“People are really fed up of this bullying,” Chris continues. “In a country that is a member of the EU, many thousands of homes are without power. The inhabitants of these houses are not to blame for the financial crisis. How can we accept that?

“We don’t like to see hypocrisy from the European technocrats. Many people think they are not interested in helping this country recover, only about saving the banks. It is not only a big economic debate but political.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“And ethical, and moral,” Despina adds, passion rising.

“Banks don’t care, but what about our European family? Our European family should care. Love and solidarity is the only way to get through. There is only one way forward and that is to be optimistic.”

“And to keep working hard,” Despina says. “And don’t give up.”