“I’d been working with people with dementia, on life-story work and using reminiscence as a way to open up conversations,” he says. ”And particularly, but not exclusively, with men, getting them to open up about their life could be quite difficult, whereas sport is one of those common currencies. You can almost guarantee 80 per cent of guys might be more prepared to talk about sport when meeting a stranger for the first time.”

That became the simple model to draw out isolated older people. If you like sport, come along and talk to other people who like sport. And it is inclusive – some might have had a stroke, others might be physically frail, then there are those with dementia.

“It’s about creating that failure-free environment, where you’re encouraging conversation again and again on a weekly basis,” continues Wilkins. “The most important thing is actually building up their emotional confidence by creating activities that are really engaging, that tap into their real interests and passions. Because then you create positive conversations and fun and banter around memories. And because people with dementia are able to tap into those more vivid longer-term memories they can still recall – everybody who was in the team, the first game they went to watch, how they got to the game – so it actually helps them to communicate in the everyday. It builds up their confidence because they’re able to still communicate with confidence around a subject that they know and love.”

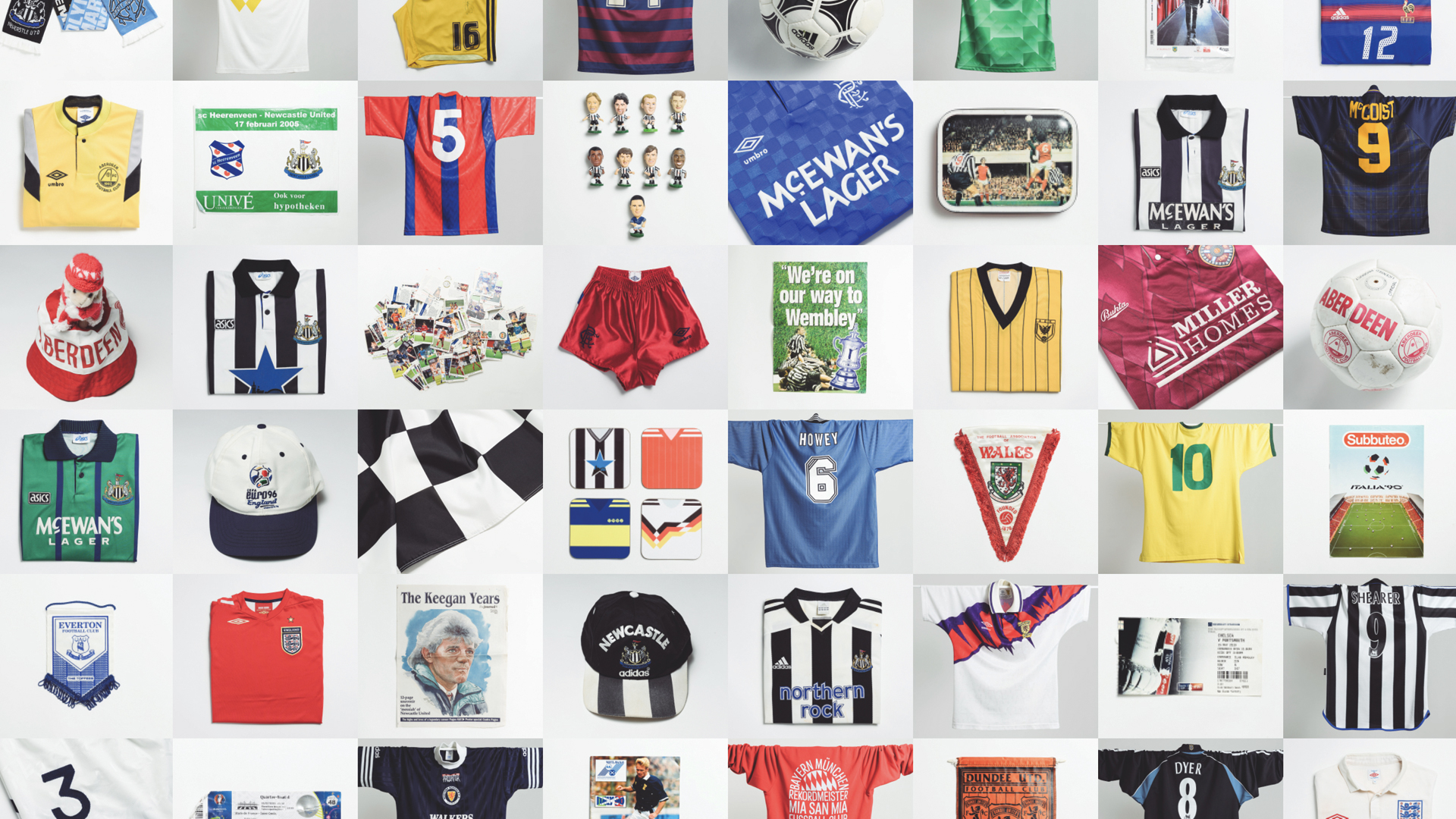

The Sporting Memories Foundation runs 130 free weekly clubs that were attended by 57,600 people in 2019. And during lockdown, when face-to-face meetings and discussion groups were impossible, they put together the Sporting Memories KITbag – containing a ball, an exercise video, and printed copies of the Sporting Pink nostalgia paper to trigger the memories of sports fans around the country.

Sport is the best form of multi-generational activityChris Wilkins, Sporting Memories

And it is not just about talking and reminiscing. Though the charity was built on improving wellbeing through reminiscence, Wilkins and the team discovered that people who may have long ago hung up their football boots still had some of the old competitive instinct.

“We thought all we would do was talk about sport and memories. But we also now encourage people to take part in physical activity – and that’s why we get funding now from the likes of Sport England, Sport Scotland and Sport Wales – because we’re actually able to get the most inactive people active again.

“People who really enjoyed sport often self-exclude themselves from taking part in activities through embarrassment or fear of not being able to keep up or remember the score or what to do. But because they are with their mates, they want to have a go. There are things like New Age Kurling. We had a whole group go to play golf for the first time in years, and some for the first time ever. It also meant some people who had self-excluded were the experts again. So it’s reconnecting them with sport.

“The other thing is that sport is, for me, by far the best form of multi-generational activity. It brings up so many shared memories. Everyone might have their own memory of an England v Germany game, the first football match they watched live or their first match for their school team. So it does bring multiple generations together really well.”

Just as researchers are discovering just how much the power of music can help some people living with dementia, talking about shared passions such as sport can also build connections. And conversation that start with recollections of football matches from 50 years ago can move into vital discussion about health issues that many men and women can find tough to broach.

“A lot of people could be suffering depression based on being isolated – so some of the ways people present an inability to communicate might not just be about memory. It might be a consequence of being isolated and depressed, and out of practice at communicating,” says Wilkins.

“So this is a way to get into the habit of talking and remembering again. It is more about helping them to communicate confidently, which has a massive impact on feelings of wellbeing and being able to live well with dementia.

“When you start laughing again, joking with people, or having people listen to you then you feel better and might feel more up for taking part in other things. You can’t turn back that clock or improve people’s memories per se but it is about people being able to live happier, more independent lives for longer because you are not on a spiral of decline by living better with it.”

There is an added poignancy, of course. Far too many footballers end up with dementia – a legacy of too much heading and too-heavy balls.

Wilkins explains that they have been training former professional footballers to facilitate their own group – resulting in a new private online group, just for former pro players – a safe space to talk through reminiscences and also their health concerns now.

“We’ve got two online groups for former professional footballers, but they are closed – it’s almost giving them a safe space where they can talk about their former antics. Very few of which are publishable!” laughs Wilkins.

As Euro 2020 nears its conclusion, new memories are being made all across the continent. For some it may be the first tournament they will remember – and it might just stay with them forever.