“There are differences between the summer and Christmas at both household and provisional level,” she tells The Big Issue. “Very few organisations are open over the Christmas period. Public sector organisations in particular have an extended break so all those touchstones and services that people rely on are not available. For volunteers who help out for 11 months of the year, it’s very hard to ask people who give everything to skip Christmas with their family.

“On a household level there are increased costs around that period, whether they are heating bills or gifts for children. There is also an emotional pressure that is more intense around the Christmas period that families are expected to be happy, for the children to feel loved and spoiled, there are these images in adverts of the perfect family.

“If you are under stress already then there can be a lot of disappointment with children and adults if they cannot live up to that.”

Turning to foodbanks

That’s not to say that foodbanks don’t provide vital help at Christmas. They are so deeply baked into our food system for the 2.2 million people who are severely food insecure in Britain. Foodbanks pick up the slack now that the safety net has been eroded by years of government-led austerity.

The Trussell Trust, the charity behind the UK’s biggest foodbank network, is already bracing itself for impact over Christmas – last year they gave out 185,000 emergency parcels, this year they expect that number to be dwarfed. On the evidence of their summer figures – handing out 823,145 parcels between April and September, a 23 per cent increase on the same period the previous year – they won’t be far wrong.

North Paddington foodbank is in one of the wealthiest parts of London, but manager James Quayle is expecting demand to skyrocket this Christmas. More than 90 households are forced to visit the foodbank per week on average, but recently those figures have been rising to more than 120.

“Over the last two months we’ve seen a 25 per cent rise in people who need to use the service,” he tells The Big Issue. That demand will keep increasing until it peaks over the Christmas week, he says, and is unlikely to start falling until schools have reopened after the holidays.

The foodbank also draws greater attention at Christmas because of the seasonal tradition of giving to those less fortunate, Quayle explains, which has a financial benefit for the services the team is trying to provide. But the foodbank, with its resources already stretched, doesn’t see its capacity go up.

Quayle is concerned about what the outcome of this week’s general election could mean for foodbanks, explaining that it could signal a need to focus on more than distributing as many tins as possible. “You’ll hear all of these foodbanks talking about how many packages they’re giving away, but there’s no information at all about the quality of these packages or whether the person they gave that food to had their allergy requirements or their medical needs met. Or even their preferences, which foodbank users have as much of a right to as anyone.”

The manager says that if holiday hunger and food poverty are to be tackled, it will have to start with an overhaul of the benefits system. “We need a system that acts as an investment in people rather than actively working against them,” he says. “At the moment, all the evidence is there that the government would prefer to not pay people and they want to make it as difficult as possible for people to access the benefits they’re entitled to, in the hope that people will give up. I’ve seen it time and time again.”

Rising debt

Debt is a constant issue for most of the families he meets in the foodbank, he says, but “Christmas compounds existing problems, meaning anyone who’s financially squeezed is squeezed even tighter”. Quayle explains that the pressure of providing a good Christmas for one’s family while compensating for the higher costs of the season, like more mouths to feed when schools close, pushes some to the brink. “It can be the difference between being able to afford to feed yourself and having to come to a foodbank.”

It’s not just the overwhelming pressure to buy presents that is pushing people towards the foodbanks – it’s fuel poverty too. Foodbanks get busier as soon as the temperature drops, Quayle says, because people have had to put the heating on. “Most people are on a key, which is more expensive anyway, and the cost is more immediate too. People can’t afford to heat their homes and eat.” Some of the UK’s poorest people pay up to £200 a year more because they are on pre-paid meters.

The cost of failing to keep up with payments can be deadly – 16,500 deaths last winter were linked to people living in cold homes, according to regulator Ofgem, as people were pushed into the devastating position of deciding whether to eat or heat.

Prevention plans

But there are ideas on how to end holiday hunger once and for all – Widdison tells

The Big Issue about a plan to put money on cards for kids receiving free school meals so they can buy food from local shops.

She also runs a Hamper Exchange, a small project that uses a ‘buy one, give one’ model to allow people to buy a hamper of luxury food from local London firms with one gifted to a food-insecure family at Christmas.

And the charity she works for, Mayor’s Fund for London, is one of the major players behind January’s London Children’s Food Insecurity Summit at London City Hall. It’s the first time groups have come together to help the 400,000 children and young people going hungry in the English capital.

“We have a general election going at the moment and yet what we have seen dominating headlines tends to be about Brexit and not about issues like child poverty,” says Widdison. “That needs to be top of the agenda and for some reason it’s not.”

No child should go hungry at any time, let alone a time that’s supposed to be one of joy.

This Christmas election offers a chance for us to vote with our feet to say no to Universal Credit, fuel poverty and the household debt that pushes people into the choice of heating or eating. We must take it.

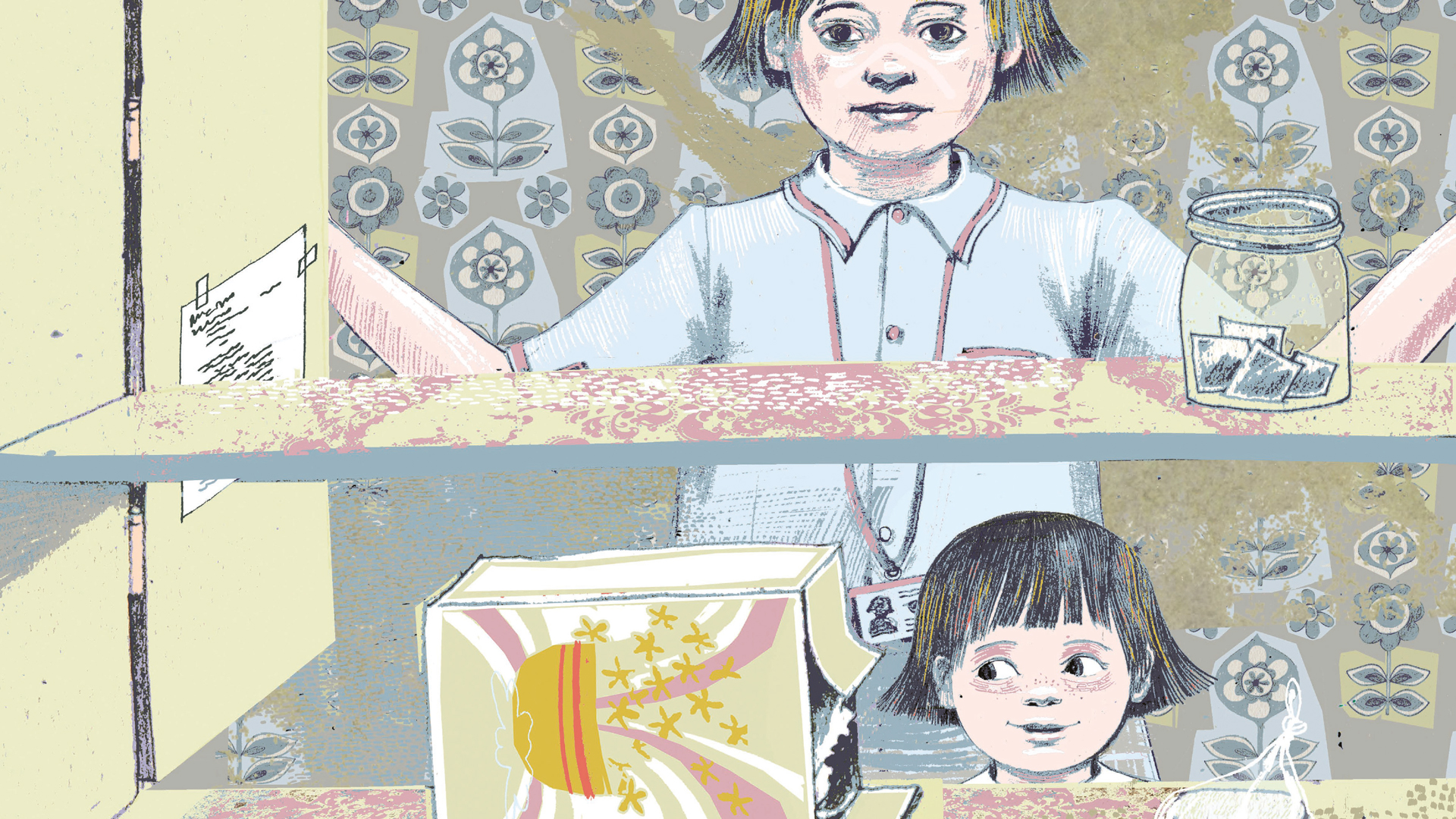

Image: Kate Milner/Barrington Stoke