When I first moved to Italy 20 years ago, I went to see a cup quarter-final between Parma and Inter. It was hard not to support Parma: it was the city where I was living, they had an astonishing team (Thuram, Cannavaro, Buffon, Chiesa and Crespo), and the girl beside me was a supporter. Parma won 6-1 and – for a long-suffering Everton fan – the football was astonishing: geometric, precise, surprising and almost inevitably winning.

I found myself playing a lot of games too, mostly amateur five-a-sides but also the odd full game. It was a different sport to English football: far less physical, it had more feints, fantasy and individualism. I’m a low-skilled player, whose strength is my voice and my eyes, not my feet, but a few teams found me a useful addition because I could pick a pass.

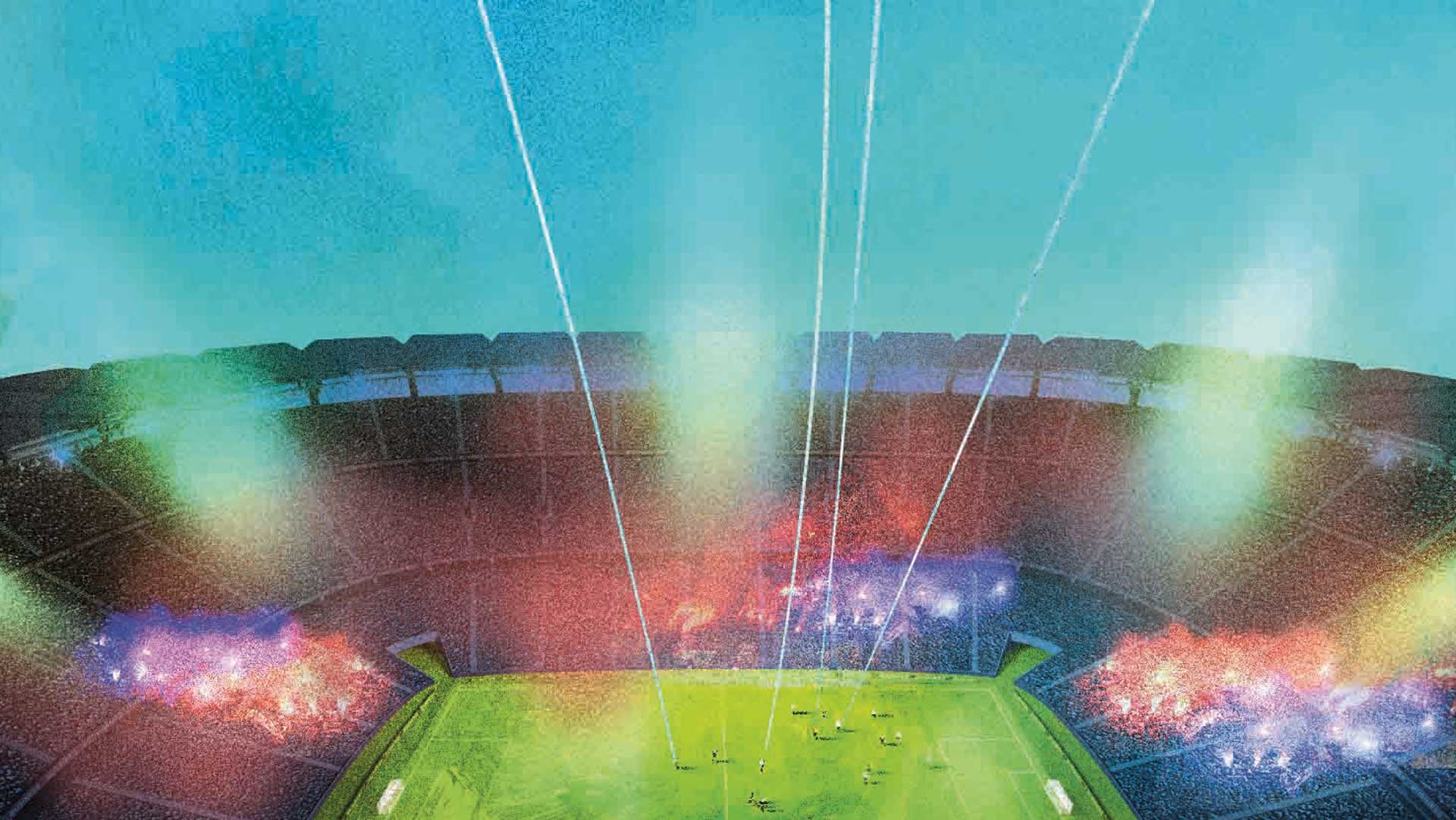

So I became pretty immersed in Italian football. But every time I went to the great stadiums to watch the pros, I was more captivated by the fans, especially the extremist elements called ‘Ultras’, than the football. They were raucous and exciting. They loved singing and fighting, and were always letting off smoke flares and often handmade bombs. They were stylish, often intimidating scallywags.

The Ultras, I discovered, were far better organised than piss-head hooligans: they had committees and sub-committees, membership registers, leaders, strategies and income-streams. An Ultra group following one of the huge teams in Serie A could number thousands of members (and big teams often had three or four main groups), so the Ultras could make or break local businesses or political, even sporting, careers.

It hadn’t always been like that. When the Ultras first appeared in the late 1960s, they had been mostly teenagers who enjoyed dressing up and getting high. They were inclusive, too, taking in the “froth of the streets” as one writer put it: the vulnerable, the lonely and those with no family. The terraces offered absolute belonging, protection and adventure. It wasn’t, originally, a politically extremist movement because one of the founding rules of the Italian terraces was that politics should be kept out.

In those heated weekly meetings, you could find yourself next to an ex-offender and a lawyer, a teenager and a pensioner

But by the turn of the century the Ultras were very different. The teenagers had become middle-aged men and, in the fights for supremacy over many decades, the toughest had risen to the top. Sporting fundamentalism had often bled into fascism. Recreational drug-use had become habitual, and many paid their bills through dealing either narcotics or simply tickets. There were many deaths, usually accidental but also, sometimes, deliberate assassinations which suggested some Ultras weren’t petty but professional criminals.