Hancock, taking his lead from these technology giants, envisages AI playing a central role in prevention and diagnosis. Doctors could deploy systems that monitor if a patient is taking their correct prescriptions. But these platforms are not without their faults, and although it’s still early days, incidents with both Watson and DeepMind have highlighted ethical issues with unfiltered implementation of AI services.

In July, internal IBM documents obtained by health news site Stat alleged that Watson was recommending “unsafe and incorrect” cancer treatments in certain cases. DeepMind, on the other hand, landed London hospital The Royal Free in hot water last year after the hospital broke privacy laws by handing over the personal data of 1.6 million patients for DeepMind’s AI-powered Streams app.

Bias

AI’s problems are not only limited to healthcare, and the technology’s major criticism right now is that of bias. There are countless instances of bias ruling AI platforms. PredPol is an AI algorithm used in the United States that predicts when and where crimes will happen. In 2016, PredPol was found to be leading police to neighbourhoods with a higher proportion of minorities, despite the crime rate in those areas telling a different story.

This bias, borne out of the natural prejudices in data input by humans, is only amplified when left to an automated system, as proven by examples like PredPol. Add a purposeful desire to save money into the mix, and we’re left with potentially dangerous consequences. We need only look to Volkswagen’s doctoring of AI software to cheat diesel emissions testing to see how AI in the control of private companies can lead to undesirable outcomes.

Discussing the ethics of bias in AI, David Magnus, director of the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics, writes on the Stanford Medicine blog that “you can easily imagine that the algorithms being built into the healthcare system might be reflective of different, conflicting interests”.

“What if an algorithm is designed around the goal of saving money? What if different treatment decisions about patients are made depending on insurance status or their ability to pay?” he asks.

Opponents are determined to ensure any such rollout of AI in the NHS is monitored closely.

The implementation of AI must be examined, monitored, improved and kept in check.

A Lords committee report examining the ethical and social implications of AI concluded earlier this year that it should not be acceptable to deploy any AI system that could have a substantial impact on an individual’s life “unless it can generate a full and satisfactory explanation for the decisions it will take”.

When looking at the handling of sensitive data, the report said there must be no repeat of the Royal Free controversy: “Maintaining public trust over the safe and secure use of their data is paramount to the successful widespread deployment of AI. ”

As the NHS continues to endure financial and staffing challenges, and while private organisations, like Google, are introduced, it doesn’t take a stretch of the imagination to understand how AI could be manipulated to save money. This will be at the cost of personalised, human care that human doctors provide (the NHS has already used AI secretaries in one hospital this year, with the government touting a £220,000 saving).

Prevention should be at the heart of healthcare; it’s a proven method of ensuring patient wellbeing by focusing on early stages. But like any new technology, the implementation of AI must be examined, monitored, improved and kept in check. If the government allows the same unchecked mishandling of mass AI rollout that led to the racial, class and economic bias seen around the world, Orwellian means will dictate NHS healthcare policy.

Ben Sullivan is The Big Issue Digital Editor.

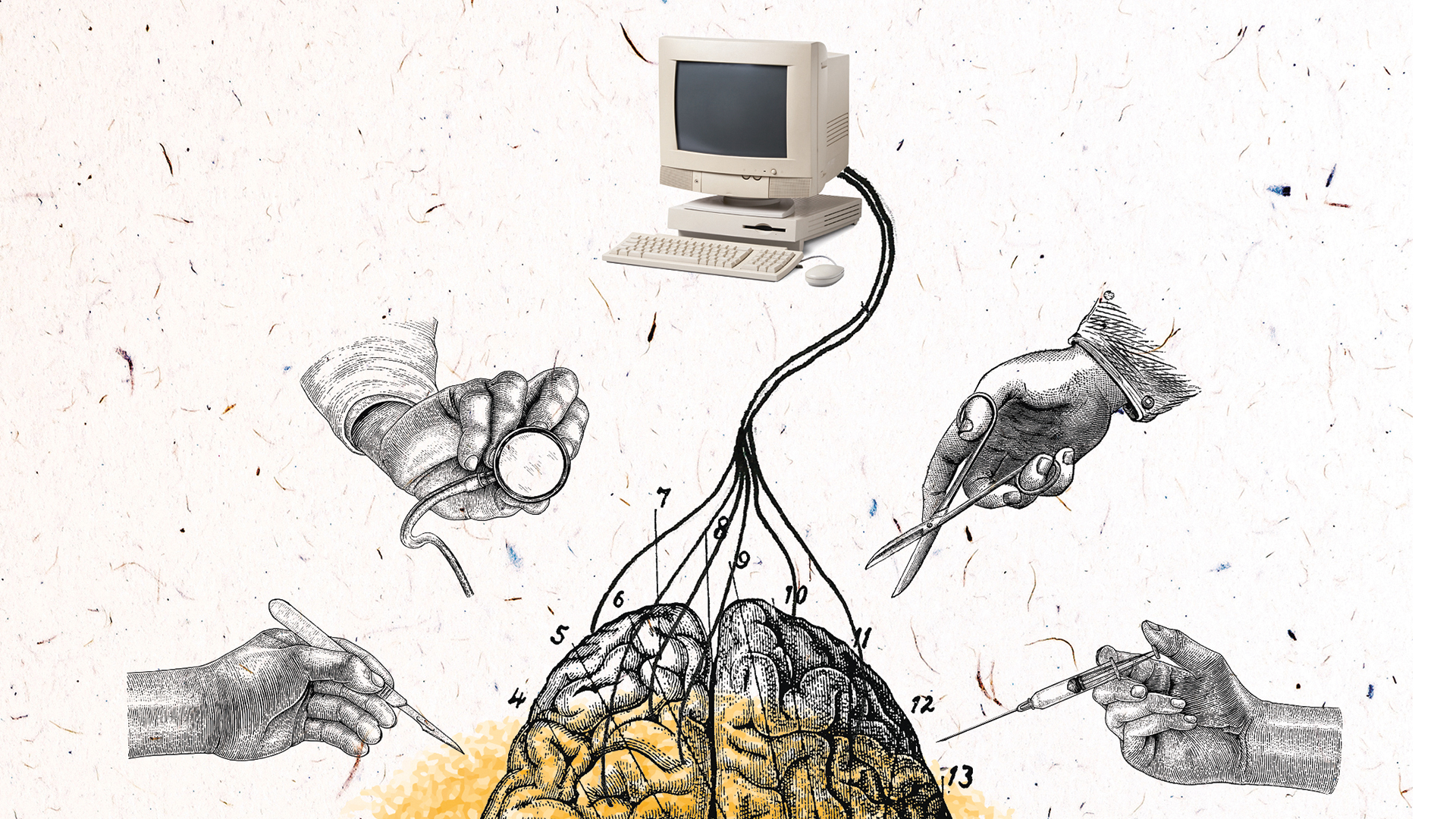

Illustration: Joshua Harrison