Indian news outlet MEA WorldWide took a more direct approach with their effort, which read: “Your unpopularity in school could kill you: Study says shunned kids linked to 34% higher risk of heart issues”.

But were these stories right?

Facts. Checked

On the whole, the news outlets played it cautious when reporting this study, which was a wise approach. It’s a robust and long-lasting study that brings up interesting conclusions about how our upbringing affects health in later life – but it is research that needs to be built on to answer deeper questions on the implications.

Researchers tracked 14,000 youngsters from Stockholm born in 1953, gauging their popularity at the age of 13 with a questionnaire.

From there, scientists kept in touch with the participants up until 2016 to measure their health outcomes.

It’s true, as reported, that boys who suffered low status among their peers at age 13 appeared to have a 34 per cent higher risk of circulatory disease in adulthood compared with those who did not, while girls had a 33 per cent higher risk.

The researchers concluded: “Peer relations play an important role for children’s emotional and social development and may have considerable long-term implications on their health.

“There is convincing evidence from neuroscience regarding how social relationships modulate neuroendocrine responses that subsequently affect the circulatory system, increasing the risk for stroke and cardiovascular diseases.”

However, the limitations around the study make it difficult to definitively prove a firm link.

Scientists acknowledge that “peer status late childhood may precede social integration in adolescence and adulthood, acting as a long-term stressor that contributes to circulatory disease through biological, behavioural and psychosocial pathways”.

While the study had a large sample size and followed participants for a long period, the information on friendship groups was based on one questionnaire taken at the age of 13. And researchers didn’t have access to information about other adversities, such as child maltreatment or peer victimisation.

Nor did they have much to go on when it comes to other health behaviours in childhood and beyond that might explain an increased risk of heart disease, such as obesity or smoking.

So it’s not clear cut, while a low number of school pals is “a long-term stressor” it is by no means a certainty that children in that position will suffer circulatory problems.

There is plenty of merit to this study that strengthens the case for early years prevention to improve health in later life. But it is not a reason for parents to panic about how many friends their child has just yet.

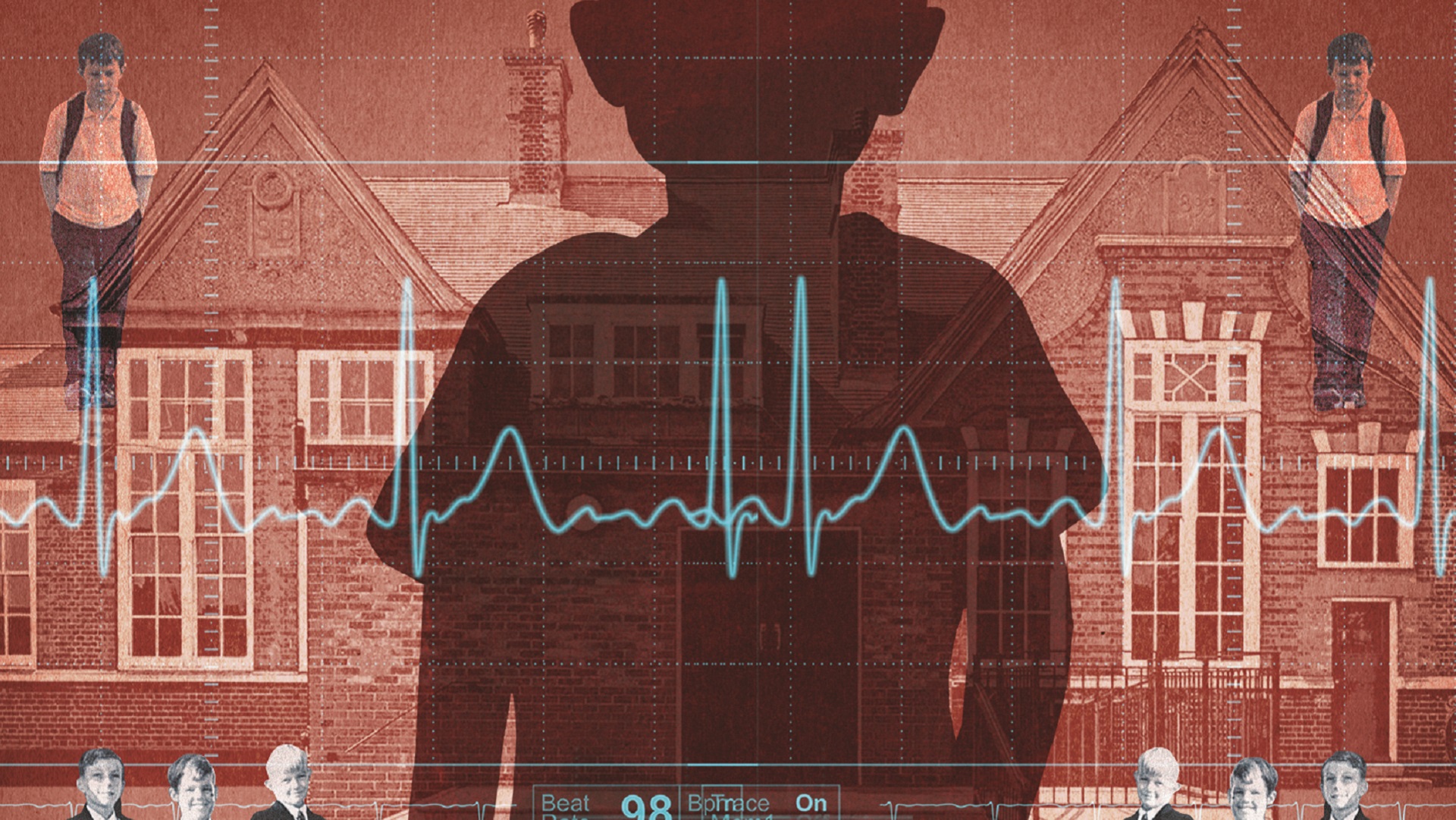

Image: Miles Cole