Sky News did the same, under the headline: “The good old days: researchers reveal when Britons were happiest.”

It wasn’t just in Britain where the study made a splash. Newsweek took a look at the story through the lens of the United States with: “This was the lowest point in US history in terms of nation’s happiness.”

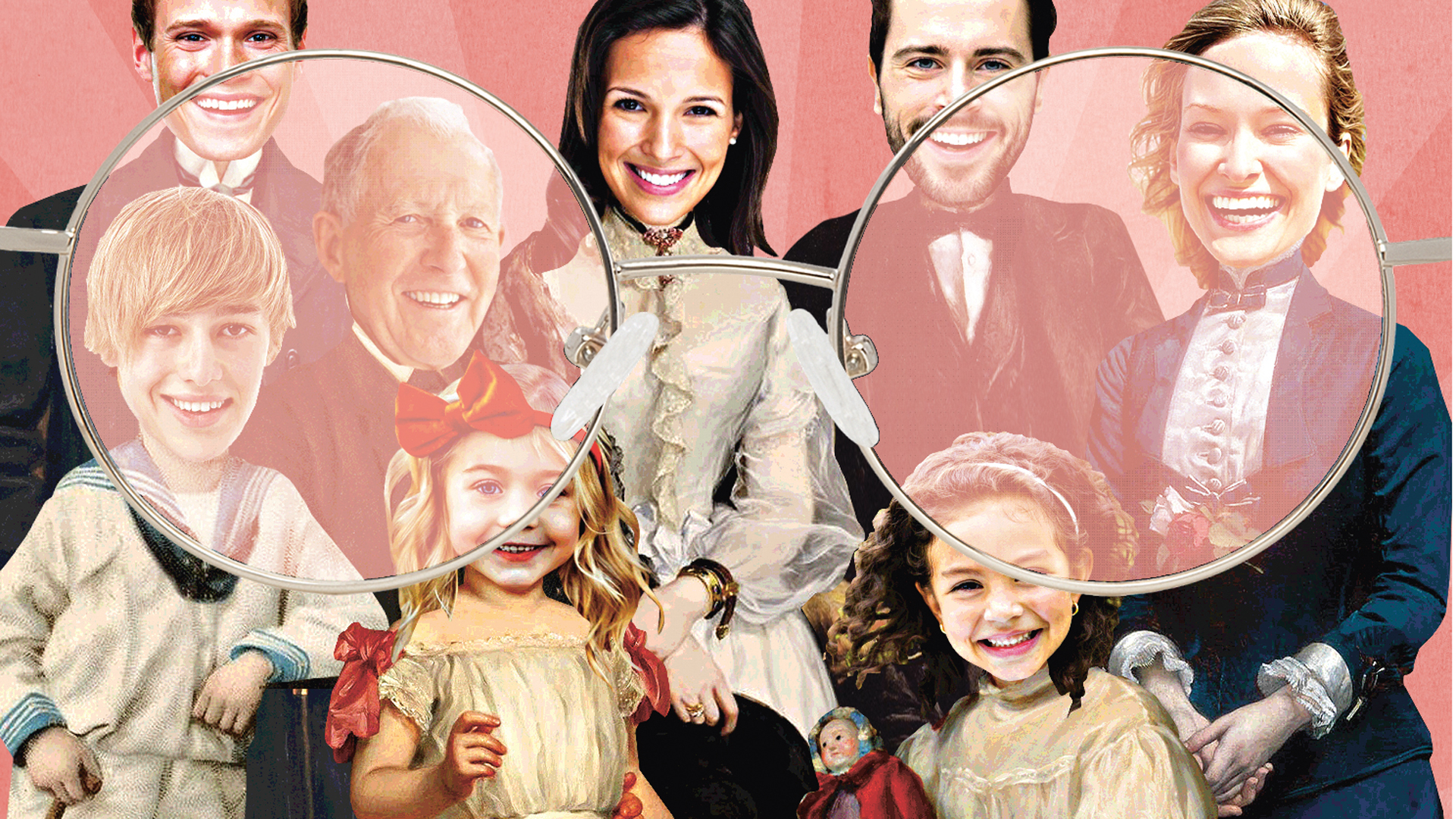

But were we really happier when Queen Victoria was on the throne or is modern life just as good?

Facts. Checked

While there was definitely a peak in happiness in the 1880s, it’s not quite as simple as saying that it was the time when the British were happiest.

There was also a peak in the 1950s and one of the report’s contributing authors, Eugenio Proto of the University of Glasgow, told The Big Issue that the information they found is not comparable across different years and eras.

He said: “I do not think it makes sense to compare two periods [that are] so different – the language has changed, as has the literary style.”

The Times and The Independent’s analyses go a step further than the press release issued alongside the study, titled Historical Analysis of National Subjective Wellbeing Using Millions of Digitised Books.

According to that release, the researchers found that increases in income do generate increases in happiness but it takes a huge rise to be noticeable on a national level. They also found that one year fewer of war had the equivalent effect of a 30 per cent rise in GDP.

However, the study does judge that the winter of discontent in 1978/79 was the worst period for national happiness in post-war Britain, while the Vietnam War and evacuation of Saigon was the same for the US.

The methodology that the researchers used has come under fire since the publication of the study. The academics were aiming to solve the problem that governments face when quantifying wellbeing by using surveys with data often only available from 2011 onwards, except some which go back to the 1970s. So they worked to the theory that books and newspaper articles are a good source of data as editors prefer to publish pieces which match the mood of their readers.

But academic and freelance writer Hannah Rose Woods questioned this methodology in tweets that she later turned into an opinion piece for the New Statesman. In it, she pointed to the fact that newspapers were predominantly made by male, middle and upper-class writers and publishers and, as a result, reflect them and not the working classes who face poverty, poor working conditions and the risk of disease.

Edge Hill University’s Dr Bob Nicholson was similarly sceptical, warning that using these tools to assess digitised books and newspapers is a good way to raise questions about curious patterns that require closer reading rather than drawing historical conclusions.

So, even as bad as the Brexit wrangling gets, it is still worth taking these articles with a pinch of salt.

Image: Miles Cole