While Turtle praised the efforts of those involved, she said it was important to recognise it “just didn’t solve homelessness” and did not reach everyone who may have needed the support.

“The number of people on the streets did go down significantly in March, but there were plenty of people left out there,” she said. “Because the focus was on bringing in people already engaged by big charities, we were mostly meeting LGBTIQ people and people with no recourse to public funds. It was the more vulnerable people within the homeless population who were left behind.”

Nearly one in five LGBTIQ people experience homelessness at some point in their lives, according to campaign group Stonewall, often as a result of discrimination or domestic abuse.

The Everyone In scheme saw more homeless people than ever with a roof over their heads, said Caroline Allouf, a volunteer with period poverty organisation Tricky Period, but it may have been “short-sighted and in effect more damaging in the long term”.

“The causes of homelessness are far more nuanced than not being able to afford a home,” she told The Big Issue. “What was missing was wrap-around support from the get-go for things like mental health, addiction and domestic violence. Without this the majority were being set up to fail.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

The outreach team for Museum of Homelessness, which operates primarily in the London borough of Islington, as well as nearby Camden and Hackney, also reported high numbers of people with no recourse to public funds (NRPF) still sleeping rough during lockdown.

The NRPF hostile environment policy means some migrants and their families are denied access to the social security safety net, with no entitlement to welfare and benefits like child tax credits and housing benefits, because they have limited leave to remain in the UK.

Nearly 1.4 million people in the UK fall into this group, Citizens Advice research showed, disproportionately affecting people of colour.

The policy meant vulnerable people fell through the cracks of the Everyone In scheme, according to reports from the frontline and from local authorities – who, in July, asked the Government to suspend the NRPF policy so they could do more to help people in need through the Covid-19 crisis.

Emergency housing for people without access to welfare has been “patchy,” Turtle said, adding: “It’s understandable that services would be fractured – it was an emergency and everyone was doing the best they could. But the flaws need to be addressed moving forward and someone needs to have oversight rather than leaving local authorities to it.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

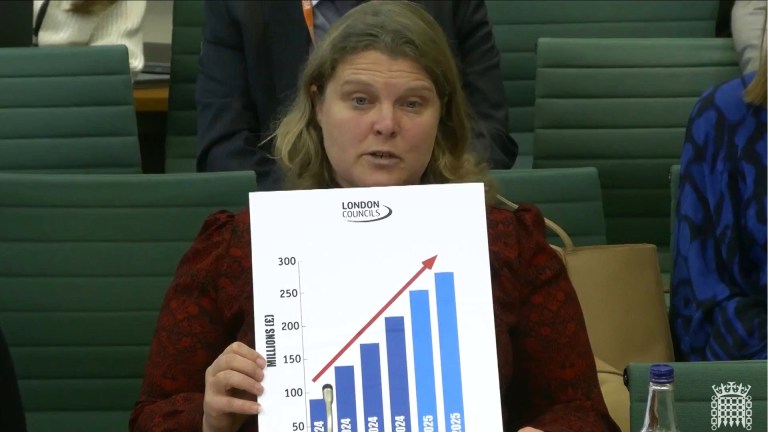

Earlier this year the Local Government Association predicted a £10.9 billion loss for councils during the pandemic and warned of cuts to vital local services that will be crucial in the post-crisis recovery effort.

Both Allouf and Turtle reported seeing significant numbers of people returning to the streets since the summer, something the Tricky Period volunteer said was “sadly inevitable” due to a lack of long-term planning. Campaigners worry thousands more could be pushed into homelessness when the furlough scheme ends this month.

The Museum of Homelessness and Streets Kitchen, whose volunteers lead Tricky Period, joined calls for Government action this week as doctors warned that the “double threat” of Covid-19 and cold conditions meant rough sleepers would die.

“It’s harsh out there. That’s the worry for the winter,” Turtle said. “It’s not just about people having somewhere to sleep, but somewhere in the day to dry off and get warm. But everywhere’s shut because of the pandemic.”

This week Mayor of London Sadiq Khan wrote to Communities Secretary Robert Jenrick calling for funding to accommodate people who would normally rely on a winter shelter in the colder months.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

He said it would be “callous and inhumane” to make people choose between living on the streets in the cold weather or risk being exposed to Covid-19 in a dorm-style shelter.

The Big Issue has approached the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government for comment.