I grew up in Jamaica with my two older sisters. I remember a lot about my early life there. I grew up in a loving home, with my grandmother looking after us. We were taught about respect. I loved my grandmother very much. She was firm, she was my first teacher. I left when I was seven but… you can take the man from the country but you can’t take the country from the man. I’ll always be Jamaican in my roots, as much as I feel very British now. Jamaicans are among the most creative people in the world, they just need more opportunities to show it. Of course I loved watching Usain Bolt run as a great Jamaican runner but I’m not going to lie, I also wished I could have competed against him running for Britain.

My father came to Britain first, then my mum, then we followed, me and my sisters. I had always been told by my grandmother that we’d be going to join my parents in Britain one day. We didn’t really know them. My father came to Britain to work, my mother was a nurse. They came here by invitation – the government was asking people from the Commonwealth to come and help make Britain great again. And those people, including my parents, came to make a better life.

I loved watching Usain Bolt run as a great Jamaican runner but I’m not going to lie, I also wished I could have competed against him running for Britain.

We had always been told the streets of England were paved with gold. ‘The houses are made of bricks and they have paper on the walls.’ We arrived at Gatwick Airport and it wasn’t quite what we expected. We didn’t see any trees! We moved to Loftus Road, home of QPR, at the edge of White City [in West London]. We had two rooms for the seven of us. But there were lots of things to do. We played a lot on the streets and in the little local park. It was summer when we arrived and playing outside was great. Until it snowed for the first time. We were excited when we saw it and we ran outside shouting ‘Snow snow snow!’ Then we picked it up and it was ‘Woah.’ Our fingers started to burn. That was a big shock.

I got racism from the first day I went to school. I was one of a very few black pupils. Kids are cruel. I didn’t realise I was black until someone told me. I told my parents, who said I would have to learn to ignore people and I’d just have to cope with it. Which I thought was great. They didn’t tell me to retaliate or hit anyone or behave in a bad way. But I was quite tough and I coped quite well. I had a few fights. I learned to run home very fast at the end of the school day. I think I owe those people something for my future success!

I didn’t know I could run until a teacher told me I was fast. There were a couple of girls at my school who could run faster. My father had always told me a good opportunity comes once in a lifetime. If you miss it, it never comes again. The strange thing was that I had several opportunities. I moved school a few times but there were always teachers or other athletes telling me I was a good runner, or could be. I wasn’t greatly interested but everyone else seemed to want me to do it. So I think I was destined to do it.

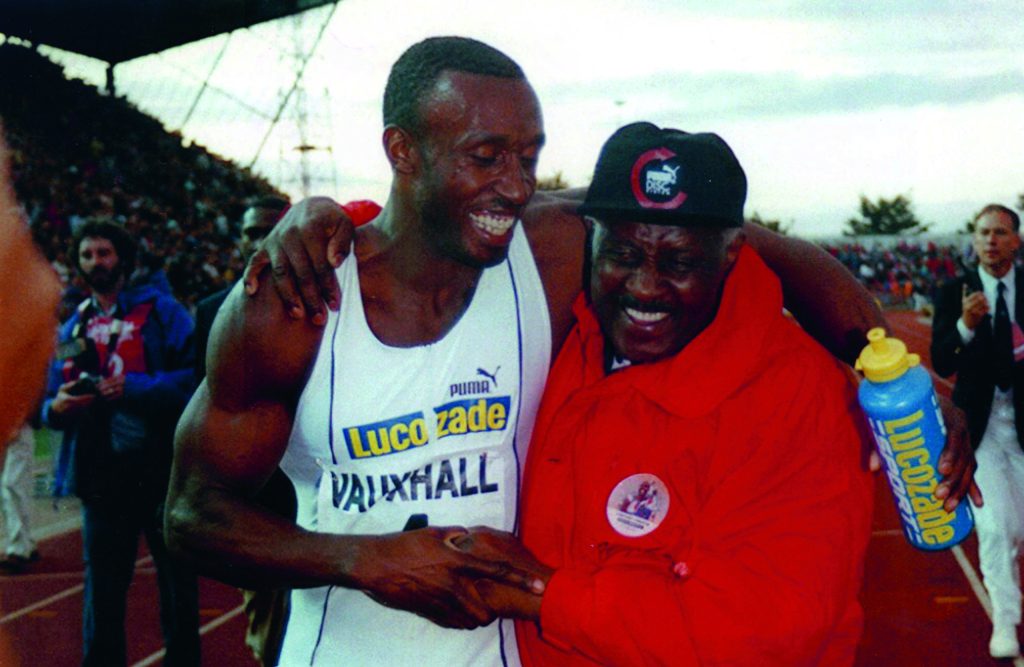

I don’t regret that it took me a bit longer than some to come into the sport. I peaked when there was no one in the country as good as me, I was just out there by myself. The timing was perfect. When I won the European Indoor 200 metres [in 1986] I think I was in the second or third string. So no one was thinking I was anything special. When I won – the first Brit to ever do it – it made me feel, yeah, maybe I could really do something with this.